Unexpectedly Heavy Stars from Long Ago Puzzle Astronomers

Ancient stars found in the outer reaches of our Milky Way are surprisingly chock full of some of the heaviest chemical elements, which could have formed in the galaxy's early history, a new study reveals.

When astronomers found abnormally large amounts of heavy elements like gold, platinum and uranium in some of the oldest stars in the Milky Way they were puzzled, because an abundance of very heavy metals is typically only seen in much later generations of stars.

To investigate this mystery, researchers observed these ancient stars over the course of several years using the European Southern Observatory's fleet of telescopes in Chile. They trained their telescopes on 17 "abnormal" stars in the Milky Way that were found to be rich in the heaviest chemical elements.

The results of the study are detailed in the Nov. 14 issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

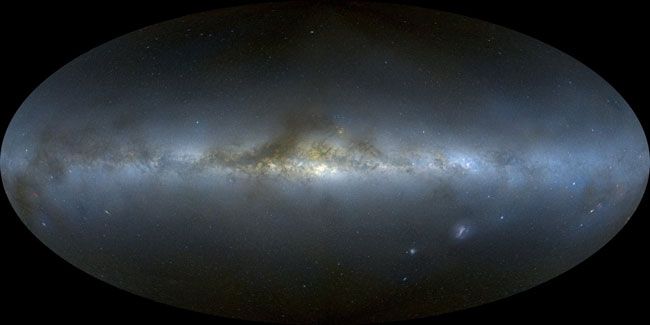

"In the outer parts of the Milky Way there are old 'stellar fossils' from our own galaxy's childhood," the study's lead author Terese Hansen, an astrophysicist at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, said in a statement. "These old stars lie in a halo above and below the galaxy's flat disc. In a small percentage — approximately 1-to-2 percent of these primitive stars — you find abnormal quantities of the heaviest elements relative to iron and other 'normal' heavy elements." [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

Hansen and her colleagues calculated the orbital motions of the stars, which led to an important clue about what kind of mechanisms must have created the heavy elements in the stars.

According to the researchers, there are two possible theories to explain these ancient stars, both centered around supernova explosions, when massive stars run out of fuel and collapse in energetic bursts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shortly after the universe was created, it was dominated by light elements like hydrogen and helium. As clouds of these gasses clumped together and collapsed in on themselves under their own gravity, the first stars were formed.

At the heart of these stars, hydrogen and helium merged together and formed the first heavy elements like carbon, nitrogen and oxygen.

When these massive stars died in supernova explosions, they spread the newly formed elements as gas clouds into space. These gas clouds eventually collapsed in on themselves again to form new stars containing the heavier elements. Throughout this process, the newer generations of stars become richer and richer in heavy elements.

After a few hundred million years, all of the known chemical elements existed. But the very early stars contained only a thousandth of the amount of heavy elements that are seen in the sun and other stars today. Hansen and her colleagues suggest that some early stars may have been in close binary systems. In such a twin star system, when one star went supernova, it would have coated its companion star with a thin layer of heavy elementslike gold and uranium.

"My observations of the motions of the stars showed that the majority of the 17 heavy-element-rich stars are in fact single," Hansen said. "Only three belong to binary star systems — this is completely normal, 20 percent of all stars belong to binary star systems. So the theory of the gold-plated neighboring star cannot be the general explanation."

Another theory is that early supernovas could shoot jets of these elements in different directions, dispersing them into the surrounding clouds of gas that eventually formed some of the stars we see today in the Milky Way.This scenario could help explain how many of the old stars became abnormally rich in heavy elements, the researchers said.

"In the supernova explosion the heavy elements like gold, platinum and uranium are formed and when the jets hit the surrounding gas clouds, they will be enriched with the elements and form stars that are incredibly rich in heavy elements," Hansen said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.