Weird 'Couch Potato' Sperm Found in Naked Mole Rats

For any other animal, sperm like the naked mole rat's would be considered faulty and infertile, new research suggests. Only about 0.1 percent of the sperm are fast, active swimmers.

Some find the animal hideous while others find it adorable, but anyway you cut it, the naked mole rat is a quirky creature. The small sausage-shaped rodent, which is neither a rat nor a mole, lives in underground burrows with up to 100 others, has a weird resistance to pain, lives much longer than comparable rodents, thrives underground and is practically blind.

Even with all these abnormalities, it turns out the naked mole rats had another weird trick up their sleeves: Even their sperm is weird.

"Surprisingly, despite the low motility and dismal features of their sperm, these naked mole rat males are fertile and fathered a number of healthy offspring per litter," study researcher Gerhard van der Horst, of the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, said in a statement.

Weird, 'eusocial' animals

These hairless animals are one of two mammals that live in "eusocial" colonies — highly structured, highly cooperative colonies similar to the way ants and bees live in groups. These colonies are ruled by one queen, who is the only female allowed to breed. For naked mole rats, only a small number of males, up to three, are allowed to breed with her.

"Once the queen has picked her consort(s) she keeps the other females and males subordinate by using physical aggression," van der Horst said. "It seems that the resultant lack of competition between breeding males for the colony queen contributed to an overall decrease in sperm 'fitness.'"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These subordinates are worker rats, which find the food and defend the burrow, and disperser males, which don’t breed with the queen but given the opportunity, will mate with an unrelated female.

Spermy problems

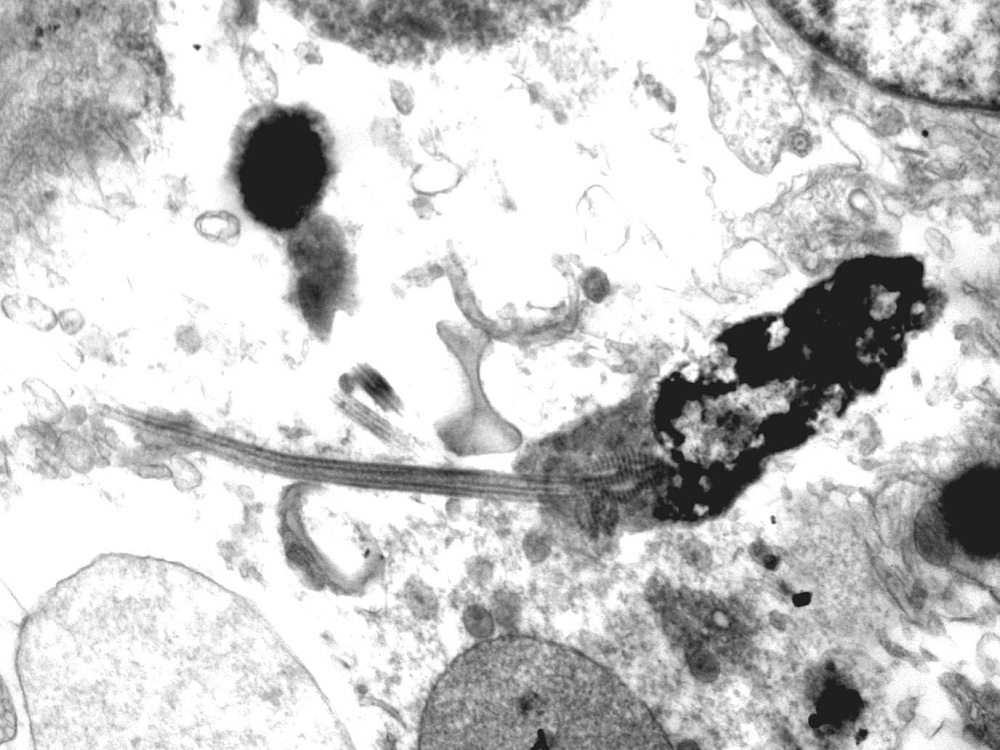

The researchers collected sperm from 15 mole rats that live in Kenya and analyzed the samples under the microscope. They saw that on average only about 7 percent of the sperm in each sample were able to swim at all. Of those moving sperm, only 1 percent were fast swimmers.

Their speed wasn't the only issue these sperm seemed to have. The sperm are very small and have an irregularly shaped head, while the sperm's chromatin (the DNA and protein mix containing the animal's genes) is dispersed rather than being concentrated in one spot, a significant cause of infertility in other animals. Like its body, the rat's sperm tail is "naked," as it is missing the covering thought to be essential for swimming through the female reproductive tract.

There didn't seem to be a difference between the sperm from the three different social classes within the colony. Maters, workers and dispersers all had inferior sperm samples with low sperm counts.

Weak competition

The researchers believe that a lack of competition for mating led to these mutated sperm, which somehow still get the job done, fertilizing up to 27 pups in a litter.

"There seems to be no need to produce perfectly formed and highly motile sperm," the authors write in today's (Dec. 5) issue of the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. "The production of high-quality, error-free spermatozoa is costly and ... there will be selection against it if the costs are not equal to or outweighed by the benefits."

The female may compensate for the "couch potato" sperm by producing a large number of high-quality eggs, the researchers suggest. They might also choose the best sperm to fertilize their eggs, a phenomenon known as cryptic female choice.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.