NASA Probe Enters Unexplored 'Cosmic Purgatory' at Solar System's Edge

After more than 30 years of traveling through the cosmos, a far-flung NASA spacecraft has entered an uncharted region between our solar system and interstellar space, scientists announced Dec. 5.

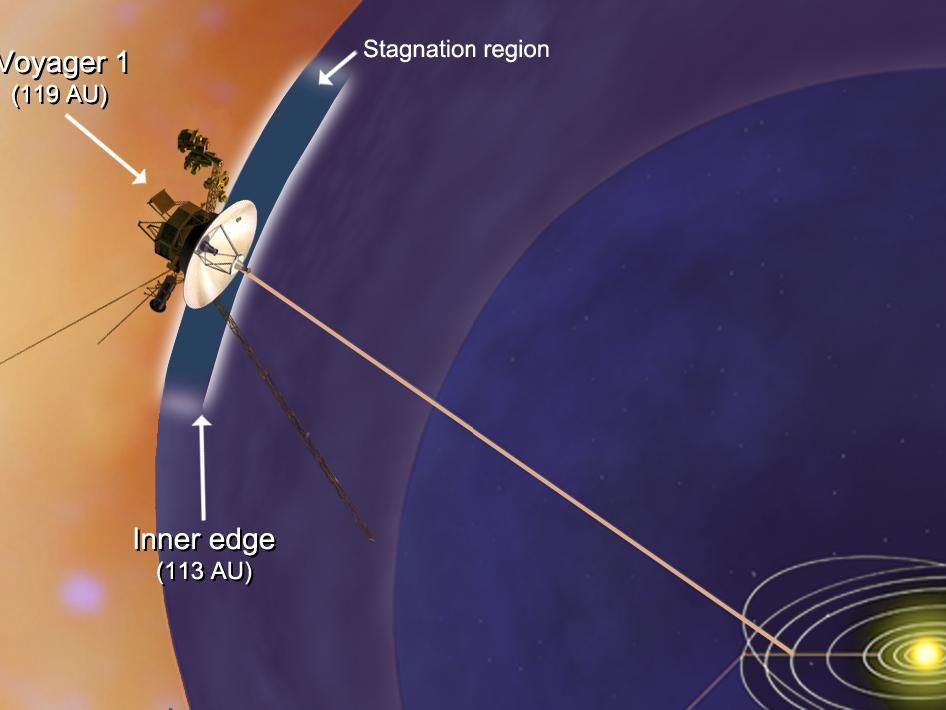

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft is about 11 billion miles (18 billion kilometers) away from the sun, and data collected from the steadfast probe indicate that it has crossed into new territory that scientists are calling the "stagnation region."

In this expanse, the flow of solar wind, which consists of charged particles that stream from the sun, has calmed down, our solar system's magnetic field appears to be compressed, and high-energy particles from inside the solar system seem to be leaking out into interstellar space. This transition zone is thought to be like a "cosmic purgatory," the astronomers said.

"Voyager tells us now that we're in a stagnation region in the outermost layer of the bubble around our solar system," Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "Voyager is showing that what is outside is pushing back. We shouldn't have long to wait to find out what the space between stars is really like." [Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes]

The latest results from the Voyager mission were presented today at the 2011 American Geophysical Union's fall meeting in San Francisco.

Journey to the edge of the solar system

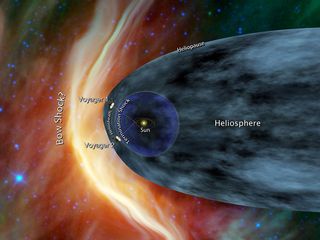

The Voyager 1 probe is currently the farthest manmade object from Earth, but has not yet reached interstellar space, Stone said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Data received from the probe indicate that it is still within the so-called heliosphere, which is a large bubble of solar plasma and solar magnetic fields that the sun blows around itself. At the perimeter of the heliosphere is the heliosheath, a turbulent region at the outer edge of the solar system.

At the edge of the heliosheath is the heliopause, a demarcation line that bounds our solar system from interstellar space. Voyager 1 covers about 330 million miles (531 million km) every year, and scientists predict that it could cross the heliopause soon — within a few months to a few years. But the precise moment when this will happen is difficult to pin down.

"I can almost assure you that we will be confused when it first happens," Stone said during a news conference today. "This will undoubtedly not be simple. Nature tends to be much more creative than our own minds."

Part of the uncertainty comes from the fact that there are still many unknowns about the characteristics of these regions at the edge of the solar system. For instance, the thicknesses of the stagnation region and the heliopause remain a mystery.

"Newton tells us the spacecraft will reach interstellar space," Stone said. "The question is, will we still be transmitting when that happens? No spacecraft has ever been there before. We continue to find our models need to be improved as we learn more about the complex interaction between solar wind and interstellar wind. The transition may not be instantaneous. There may be a turbulent interface, [and it] may take us months to get through a rather messy interface between these two winds."

Breaking new ground

In April 2010, scientists reported that the outward speed of solar wind had diminished to zero, which indicated the start of the new region. To follow up these observations, mission managers rolled Voyager 1 four times this spring and summer to investigate whether the solar wind was blowing strongly in another direction. [Voyager: Humanity's Farthest Journey ]

What the researchers found was that Voyager 1 is journeying through space in a region similar to the doldrums in Earth's seas, where there is very little wind.

Over the past year, instruments onboard Voyager 1 also found that the intensity of the solar magnetic field in the stagnation region had doubled. This increase demonstrates that inward pressure from interstellar space is causing it to compress.

"Once the wind slows down, the [magnetic] field lines get compressed and field intensity goes up," Stone explained. "That's precisely what we've seen now in the last year. Today, it's about twice what it had been for the previous four years."

As it journeys toward interstellar space, Voyager 1 has been measuring energetic particles that originate from inside and outside our solar system. Until mid-2010, the intensity of particles originating from inside the solar system had been holding steady, the scientists said.

During the past year, the abundance of these energetic particles has been in decline, reaching a point now that is half what it was throughout the previous five years. This leads the researchers to think the high-energy particles are seeping into interstellar space.

While this is going on, Voyager is also detecting a sharp increase in the intensity of cosmic rays from elsewhere in the galaxy, penetrating into the solar system from outside. This is yet another sign that the spacecraft is approaching the boundary of interstellar space.

"We've been using the flow of energetic particles at Voyager 1 as a kind of wind sock to estimate the solar wind velocity," Rob Decker, a co-investigator on Voyager's Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., said in a statement. "We've found that the wind speeds are low in this region and gust erratically. For the first time, the wind even blows back at us. We are evidently traveling in completely new territory. Scientists had suggested previously that there might be a stagnation layer, but we weren't sure it existed until now."

An ongoing voyage

NASA launched Voyager 1 along with its sister Voyager 2 in 1977 to study the outer planets of the solar system. Voyager 2 is trailing its twin counterpart, and is currently 9 billion miles (15 billion km) away from the sun. [Our Solar System: A Photo Tour of the Planets]

The instruments aboard the Voyagers are powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert the heat from plutonium's radioactive decay into electricity. The spacecraft have enough fuel to keep the instruments running until at least 2020, Stone said.

Though no one knows exactly what they will find, scientists are hoping that the Voyager probes continue to reveal exciting new discoveries about the solar system and beyond as they continue their cosmic cruise.

Until then, scientists are eagerly awaiting the next breakthrough.

"For me, it's been constant entertainment," said Eugene Parker, a professor emeritus in the department of physics at the University of Chicago. "I hold my breath as to what's going to happen next."

And for a mission that has been going strong for 34 years, astronomers have come to expect the unexpected.

"I think the entire science team — none of us could have imagined the wealth of discovery that continues today," Stone said. "No doubt there's still a lot of discovery left, and that's what science is all about."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.