Empathetic Rats Help Each Other Out

The act of helping others out of empathy has long been associated strictly with humans and other primates, but new research shows that rats exhibit this prosocial behavior as well.

In the new study, laboratory rats repeatedly freed their cage-mates from containers, even though there was no clear reward for doing so. The rodents didn't bother opening empty containers or those holding stuffed rats.

To the researchers' surprise, when presented with both a rat-holding container and a one containing chocolate — the rats' favorite snack — the rodents not only chose to open both containers, but also to share the treats they liberated.

Peggy Mason, a neuroscientist at the University of Chicago and lead author of the new study, says that the research shows that our empathy and impulse to help others are common across other mammals.

"Helping is our evolutionary inheritance," Mason told LiveScience. "Our study suggests that we don't have to cognitively decide to help an individual in distress; rather, we just have to let our animal selves express themselves."

Empathetic rats

In previous studies, researchers found that rodents show the simplest form of empathy, called emotional contagion — a phenomenon where one individual's emotions spread to others nearby. For example, a crying baby will trigger the other babies in a room to cry as well. Likewise, rats will become distressed when they see other rats in distress, or they will display pain behavior if they see other rats in pain.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, Mason and her colleagues wanted to see if rats could go beyond emotional contagion and actively help other rats in distress. To do so, the rats would have to suppress their natural responses to the "emotions" of other rats, the result of emotional contagion. "They have to down-regulate their natural reaction to freeze in fear in order to actively help the other rat," Mason explained.

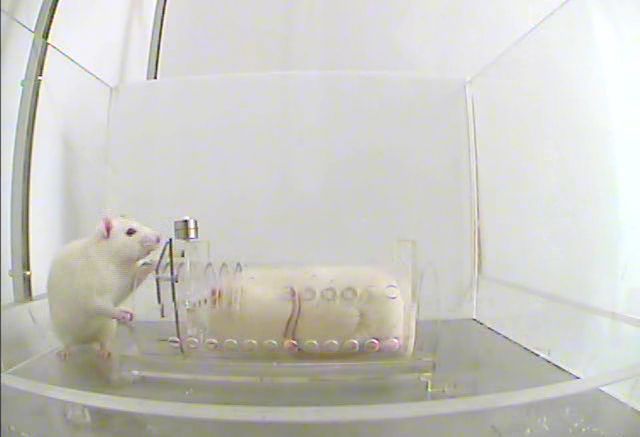

The researchers began their study by housing rats in pairs for two weeks, allowing the rodents to create a bond with one another. In each test session, they placed a rat pair into a walled arena; one rat was allowed to roam free while the other was locked in a closed, transparent tube that could only be opened from the outside.

The free rat was initially wary of the container in the middle of the arena, but once it got over the fear it picked up from its cage-mate, it slowly began to test out the cage. After an average seven days of daily experiments, the free rat learned it could release its friend by nudging the container door open. Over time, the rat began releasing its cage-mate almost immediately after being placed into the arena.

"When the free rat opens the door, he knows exactly what he's doing — he knows that the trapped rat is going to get free," Mason said. "It's deliberate, purposeful, helping behavior."

The researchers then conducted other tests to make sure empathy was the driving force in the rats' behavior. In one experiment, they rigged the container so that opening the door would release the captive rat into a separate arena. The free rat repeatedly set its cage-mate free, even though there was no reward of social interaction afterwards. [Like Humans, Chimps Show Selfless Behaviors]

True motivations

While it appears that the rats are empathetic, questions about the rodents' true motivations still remain.

"It is unclear whether the rats sympathize with the distress of their cage-mates, or simply feel better as they alleviate the perceived distress of others," Jaak Panksepp, a psychologist and neuroscientist at Washington State University, wrote in an article accompanying the study.

Mason says they don’t yet know if the free rats are acting to relieve their own distress, the distress of their cage-mates, or a combination of both, but this is definitely a topic for further research. She’s also looking to study if the rats would behave the same way if they weren’t cage-mates, and she would like to tease out the brain areas and genes involved in the behavior.

But, she says, “We now have this incredibly controlled, reproducible paradigm.” Other scientists should be able to use the model they developed to see if empathy and prosocial behavior are present in other animals, she said.

The study was published today (Dec. 8) in the journal Science.