Alien Planet Warps Its Solar System

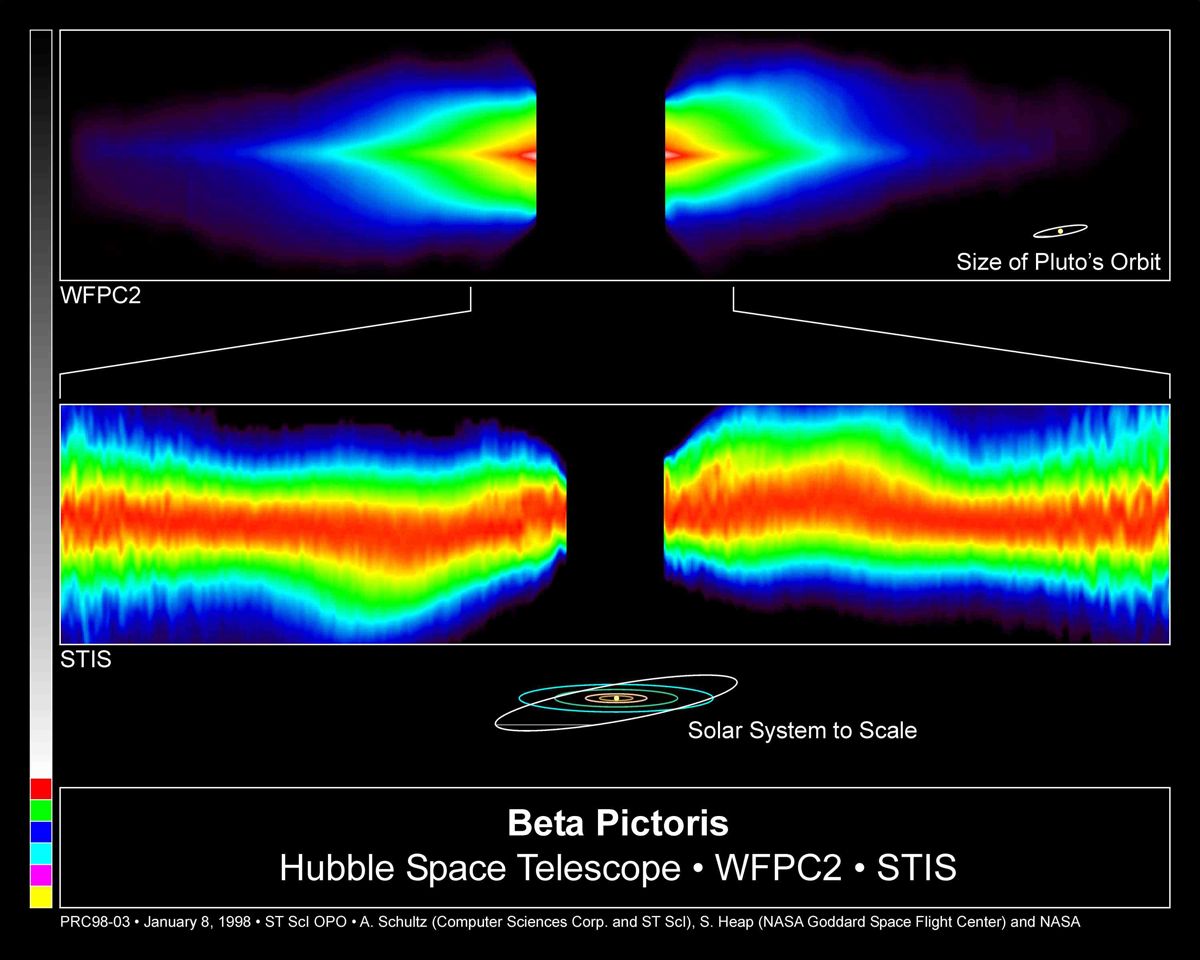

An alien planet circling around a distant star has caused a disk of debris around the system to warp into crookedness, scientists find.

The study could help illuminate the complicated mechanics at work in alien star systems.

Astronomers had originally thought a second planet in the Beta Pictoris system might have caused the warp in the debris disk surrounding the star, but the new study rules out this scenario, scientists say.

The most likely culprit is the star's first-discovered planet, a Jupiter-sized world known as Beta Pictoris b, researchers said. Though the present orbit of this planet would not create the distortion, new research indicates that the disk itself may have moved the planet from an earlier path that could have altered the shape of the disk. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Alien Planets]

One planet or two?

Gas and debris tend to orbit stars in a smooth plane around their equators, but in the year 2000 astronomers realized that the debris disk around Beta Pictoris was slightly warped.

"The inner part of the disk is tilted, and the outer part, far away from the star, is flat," Rebekah Dawson, a graduate student at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., told SPACE.com.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronomers believed a planet was creating the warp. As such a body moved through the disk, its gravitational effects would change the way the particles within the debris moved, scientists reasoned.

After a decade of searching, astronomers managed to directly image Beta Pictoris b. But, to their surprise, the orbit of the planet seemed to indicate the planet could not have created the tilt.

"If it was causing the warp, we would expect that the planet would be on an inclined orbit," Dawson said.

Instead, research published in August 2011 by Thayne Currie of NASA revealed that the planet's orbit was flat, aligned with the outer edge of the disk rather than the interior.

With this in mind, Dawson and her team modeled potential orbits of a second planet and its interactions with Beta Pictoris b, in hopes of finding a path that would explain the observations. However, the researchers were unable to simulate a planet of the right mass at the right distance to cause the warp.

Such a ghost planet would have to have formed the distortion without disrupting the orbit of the existing planet. It would have needed to be small enough to have escaped previous detection, and in a position that wouldn't have created another bend in the system.

"We considered all different possible masses and distances from the star for other planets, and were able to rule them all out," Dawson said.

Smaller, more distant planets could exist within the system, but none would be responsible for the distortion, she added.

"The fact that there is a known planet with the mass and distance that it has, means it is not possible for another planet to be making the warp," Dawson said.

The researchers detailed their findings in a paper published in the December issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A changing orbit

When Dawson and her team realized the tilt could not have been created by a second planet, they decided to re-examine the first.

If Beta Pictoris b, in its past, had an inclined orbit, it could have sufficiently shifted the dust and rock within the disk. At the same time, friction between the planet and the dust and rock of the disk could have dragged the planet enough to alter its orbit, flattening it into the same plane as the debris.

"The planet is losing energy to the disk as it passes through," Dawson said.

Such a scenario could reveal a great deal about the history of the disk, which is made up of colliding rocks and dust in the mature system, similar to the Kupier belt and the asteroids between Mars and Jupiter.

"These are the leftover rocky things that didn't become planets."

These tiny pieces are too small to see individually, but detailed modeling of the evolution of the system could allow astronomers to study this challenging body.

"It would tell us a lot about the disk and the properties of the planetesimals that are very hard to actually probe," Dawson said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.