NASA Has Lost Hundreds of Its Moon Rocks, New Report Says

NASA has lost or misplaced more than 500 of the moon rocks its Apollo astronauts collected and brought back to Earth, according to a new agency report.

In an audit released Thursday (Dec. 8), NASA's Office of Inspector General states that the agency "lacks sufficient controls over its loans of moon rocks and other astromaterials, which increases the risk that these unique resources may be lost."

The report stresses the importance of maintaining stricter guidelines for the release of lunar materials to researchers, and more meticulous inventory procedures for their storage and return.

"NASA has been experiencing loss of astromaterials since lunar samples were first returned by Apollo missions," inspector general Paul K. Martin detailed in the report. "In addition to the Mount Cuba disk, NASA confirmed that 516 other loaned astromaterials have been lost or stolen between 1970 and June 2010, including 18 lunar samples reported lost by a researcher in 2010 and 218 lunar and meteorite samples stolen from a researcher at [NASA's Johnson Space Center] in 2002, but since recovered."

And while the agency reported the 517 missing moon rock samples, even more of these precious materials may have gone astray, according to the report. [Photos of NASA' Apollo Moon Missions]

Missing moon samples

Martin's office audited 59 researchers who had received samples from NASA, and found that 11 of them, or 19 percent, could not locate all of the borrowed materials.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The report also found that the Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston had records of hundreds of samples that no longer exist, and loans to 12 researchers who had died, retired or relocated, sometimes without the office's knowledge and without returning the samples.

"The Curation Office did not ensure that these loaned research samples were efficiently used and promptly returned to NASA," Martin wrote. "For example, we learned of one researcher who still had lunar samples he had borrowed 35 years ago on which he had never conducted research."

In response to the inspector general report, the agency is looking into modifying their loan agreements and procedures.

"NASA is committed to the protection of our nation's space-related artifacts, and sharing these treasures with outside researchers and the general public," NASA spokesman Dwayne Brown said in a statement. "We agree with the recommendations contained in the recently released Inspector General report examining NASA's controls over loans of moon rocks and other astromaterials to researchers and educators. Actions will mostly result in changes to loan agreements and inventory control procedures."

The agency does not consider lunar rocks and other moon samples to be at high risk, Brown added.

But perhaps the losses need to be put into context, said Robert Pearlman, editor of collectSPACE.com, an online publication and community for space history and artifact enthusiasts.

"According to the Office of Inspector General, out of the 26,000 samples NASA has on loan, it has lost just 517," Pearlman told SPACE.com. "That's not to excuse the space agency and its curators, but with so many samples spread across the globe, some losses are probably to be expected."

Still, the misplaced moon samples are truly regrettable, he added, and could be an indication of a broader issue within the public psyche.

"Maybe it is a sign of the times that some scientific researchers and educational organizations that were loaned samples and then lost them would no longer recognize the rarity and historical significance of the lunar material," Pearlman said. "It seems that the moon, or at least its exploration by humans, has lost some of its shine over the past four decades."

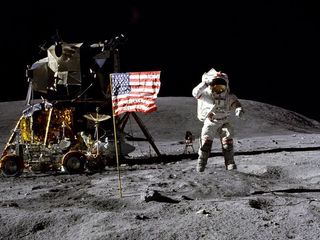

Back from the moon

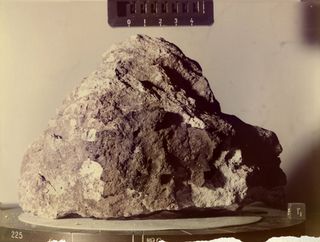

From 1969 to 1972, 12 astronauts landed on the moon during the agency's Apollo program. A total of 842 pounds (382 kilograms) of lunar rock and soil came back with these astronauts over the course of six moon landings.

NASA regularly loans moon rocks, meteorites and samples of comet dust to museums, researchers, educators and institutions around the world. The Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office maintains 140,000 lunar samples, 18,000 meteorite samples, and about 5,000 solar wind, comet and cosmic dust samples, the report said.

"As of March 2011, over 26,000 of these samples were on loan for scientific study, educational pursuits and public outreach purposes," Martin wrote.

Maintaining better control of these samples returned from space will likely require a much larger overhaul of the system currently in place.

"Perhaps the bigger question is why these samples were not actively being used — either in current research or educational lessons — such that their loss, other than to theft, would be far more conspicuous," Pearlman said. "Why were there researchers who received samples and didn't use them? Why were educational samples entrusted to just one staff member in such a way that upon that person's passing, no one else was aware of them?"

The space agency is committed to making changes to address the issues cited in the new report, Brown said.

"Over the history of the program, NASA has continually reviewed, assessed, and updated its procedures to mitigate incidents that result in loss of samples," he said. "NASA will incorporate the [Inspector General's] recommendations within new procedures and processes already in work. NASA plans to complete the entire updating process within 9 months."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.