Humans Originated Near Rivers, Evidence Suggests

Just as great civilizations once emerged along the banks of major rivers such as the Tigris, Euphrates, Ganges and Nile, the ancestors of humans might have originated on riversides too, scientists find.

This discovery could help us better understand the environmental forces that shaped the origin of the human lineage, such as factors of the landscape that prompted our ancestors to start walking upright on two legs, researchers said.

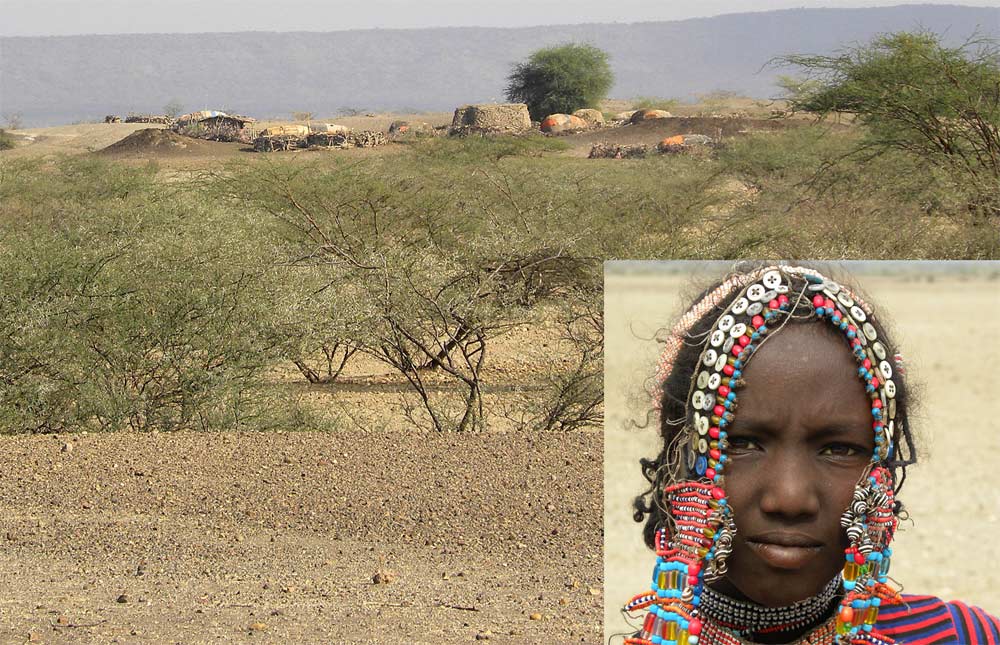

What may be the earliest known ancestor of the human lineage, the 4.4-million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus, or "Ardi," was discovered in Aramis in Ethiopia. The precise nature of its habitat has been hotly debated — its discoverers claim it was a woodland creature far removed from rivers, while others argue it lived in grassy, tree-dotted savannas.

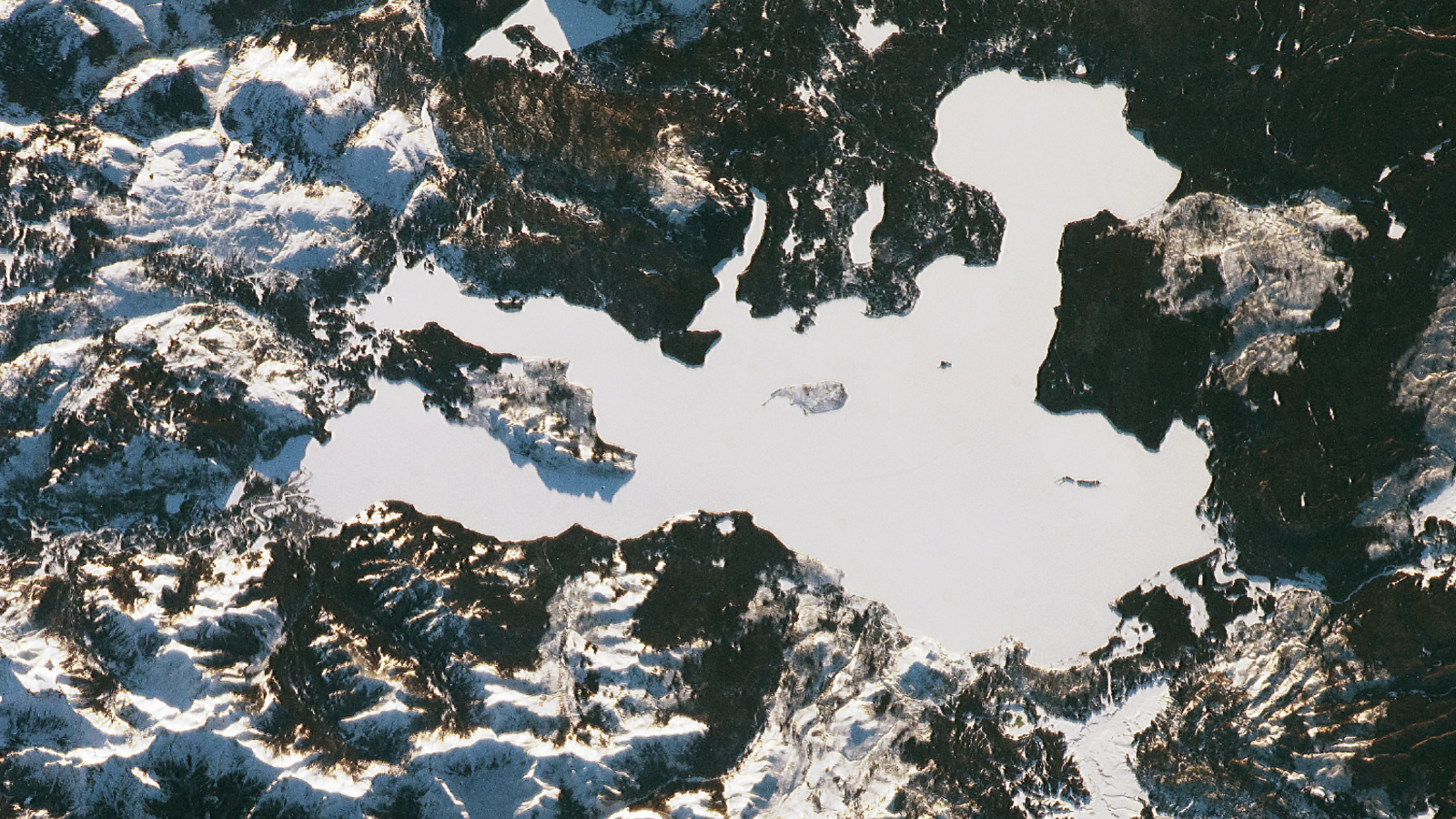

To learn more about what the area was like back then, scientists investigated sediments from the site where Ardi was excavated. They noticed layers of sandstone that were likely created by ancient streams regularly depositing sand over time. These rivers may have reached up to 26 feet (8 meters) deep and 1,280 feet (390 m) wide.

The researchers also looked at isotopes within these sediments. All isotopes of an element have the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons — for instance, carbon-12 has six neutrons, while the heavier carbon-13 has seven. The grasses that dominate savannas engage in a kind of photosynthesis that involves both carbon-12 and carbon-13, while trees and shrubs rely on a kind of photosynthesis that prefers carbon-12.

All in all, carbon isotope ratios suggest the environment back then was mostly grassy savanna. However, the way in which those ratios fluctuate suggests riverside forests also cut through this area. Oxygen isotope ratios that are closely linked with climate also suggest the presence of streams, researchers added.

"Great rivers such as the Nile and Ganges have been very important in our history, and we now find that rivers might have also helped play a key role at the dawn of humanity," researcher Royhan Gani, a geologist at the University of New Orleans, told LiveScience. [Photos: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Knowing the context in which our distant relatives dwelt when key traits such as walking upright evolved can shed light as to why such characteristics developed in the first place. For instance, as savannas began dominating what were once primarily forests, it might have made more sense to start walking on two feet to conserve energy when moving through tall grasses.

"We now want to get a better understanding of why and how climate was shifting over a much larger area to get an even better idea of how the environment changed," Gani said.

Royhan Gani and his wife Nahid Gani detailed their findings online Dec. 20 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.