Mighty Arms Helped Extinct Cats Keep a Mouthful of Fanged Teeth

Sabertooth cats and other super-toothy predators apparently possessed mighty arms that they used to help them kill.

The beefy arms would have served to pin down prey and protect the ferocious-looking teeth of the feline predators, which were actually fragile enough to fracture, scientists find.

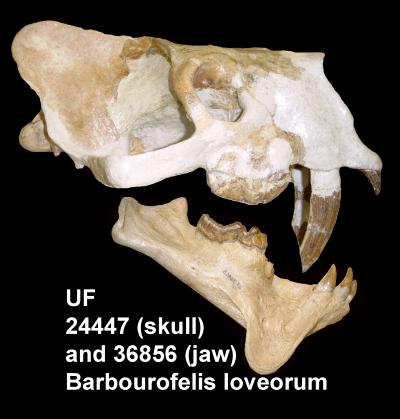

The finding also may hold for other knife-fanged prehistoric carnivores; long before sabertooth cats evolved, a number of now-extinct toothy hunters once roamed the Earth. These included the nimravids, or false sabertooth cats, which lived from 7 million to 42 million years ago alongside a sister group to cats known as barbourofelids, which lived from 5 million to 20 million years ago.

"If you saw one of these animals you'd probably think it was a cat, but true cats didn't evolve until millions of years later," said researcher Julie Meachen-Samuels, a paleontologist at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in Durham, N.C.

Nimravids and barbourofelids left no living descendants, but fossils revealed their fangs came in a wide range of shapes and sizes. Some were shorter and round, while others were longer and flattened. Some even were serrated like a steak knife, Meachen-Samuels said.

Sabertooth cats had long fangs that looked formidable but were fragile compared with those of modern felines. The daggerlike teeth were more vulnerable to fracture.

"Cats living today have canines that are shorter and round in cross-section, so they can withstand forces in all directions," Meachen-Samuels said. "This comes in handy for hunting — their teeth are better able to withstand the stress and strain of struggling prey without breaking."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Previously, Meachen-Samuels and her colleagues found the sabertooth cat Smilodon fatalis had powerful forelimbs — stronger than those of any cat today.

"Thick, robust bones are an indicator of forelimb strength," Meachen-Samuels said.

The scientists conjectured these heavily muscled arms helped the cats to pin down prey while also protecting their fangs from fracturing as they bit into their struggling victims. As Meachen-Samuels analyzed the fossils of other toothy predators, she had a hunch they might have possessed beefy arms as well.

"I started noticing this trend," she said.

Meachen-Samuels measured the upper canines and arm bones of hundreds of museum specimens of extinct cats, nimravids and barbourofelids that once roamed North America. She also measured the teeth and arm bones of 13 cat species living today, such as the tiger, all of which have conical teeth. [Gallery: Tiger Species of the World]

After comparing the dimensions of the teeth with those of the arms, Meachen-Samuels found something that was true for all the groups of predators: the longer the teeth, the thicker the arms. This discovery held up even after taking into account the fact that bigger species generally have bigger bones.

This deadly combination presumably arose repeatedly in different toothy predators over time because it gave them an advantage when catching and killing prey.

"The predators needed to hold prey down first before making a killing bite at the throat," Meachen-Samuels told LiveScience. "This mode of prey killing evolved several times independently in many lineages of carnivores, not just cats. It wasn't just saber teeth that evolved but an entire suite of prey-killing adaptations — forelimbs and teeth together."

Meachen-Samuels added, "This killing mode was not uniquely limited to sabertooth cats, but extended into many other carnivores and possibly even some marsupials."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Jan. 4 issue of the journal Paleobiology.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.