Computer Game Teaches Kids How To Play Nice With Dogs

Can kids learn to let sleeping dogs lie by playing a computer game? A new study finds that the answer is "sort of."

A software program designed to teach kids how to interact safely with dogs does teach valuable lessons, according to the research. But the children have trouble translating their computer learning into real-world situations with a live dog. The findings are important because children make up the majority of the 5-million dog-bite victims in the United States each year, according to study researcher David Schwebel.

"It's a much more major public health problem than I think most people realize," Schwebel, a child psychologist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, told LiveScience. "Certainly dogs are great companions , great pets, and they're safe and fun most of the time. But they can be dangerous — they are animals."

About 217 3- to 5-year-olds per 100,000 in the United States were bit by a dog badly enough in 2009 to need medical attention, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Part of the problem, Schwebel said, is that kids are active and unpredictable, and can stress out dogs. But another dog-bite risk is an issue of child development. Before the age of 4 or so, children don't understand that other people (and animals) have thoughts and desires different from their own. So when a child sees a sleeping dog and wants to pull its ears, that kid can't comprehend that the dog might not be in the mood for ear-pulling. [Infographic: When Dogs Bite]

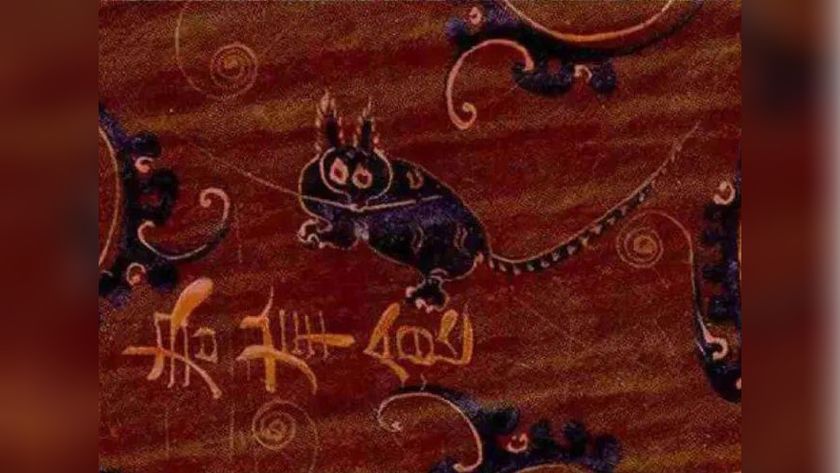

The Blue Dog

To try to teach kids how to properly interact with their pets, the nonprofit organization The Blue Dog Trust developed an interactive computer game called "The Blue Dog." The game sets up animated scenarios where kids can choose whether to play with a dog that is napping, eating or otherwise indisposed. If the kids make the unsafe choice — sneaking up on a dog during dinnertime, for example — the dog will growl and bark.

Schwebel and his colleagues wanted to find out if the program really worked. They recruited 76 3- to 5-year-old kids from Birmingham, Ala., and Guelph, Ontario, alerting parents to their study via churches and schools. All of the children had pet dogs, as the software is designed to teach kids how to play with their own family pets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each kid came to the psychology lab and completed three dog-related tasks. In the first, researchers showed the children pictures of dogs in different situations and asked if the child would go pet the dog in each. In the next tasks, the researchers acted out make-believe scenes with the children using a dollhouse and dolls. For example, they might tell the child that it was playtime for the dog figurine (part of the doll set), but the dog was feeling sick. The children were then asked to play out what they think should happen next.

Finally, the kids went into a room with a real dog, where they were rated on their safe and unsafe behaviors. (All the dogs were trained therapy dogs.)

Those three tasks gave the researchers a score for how much each child already knew about dog safety and how well they put their knowledge into practice. After the tasks, the kids and their parents went home with a copy of one of two education software discs: "The Blue Dog" or "The Great Escape," a fire-safety program. Both groups were told to use the software frequently.

Learning curve

After three weeks, the kids returned to the lab to complete the same three dog-safety tasks again. The research turned up "mixed news" for kids who played the dog-safety computer game, Schwebel said.

"What we found is that children did learn. … They did better on the pictures," he said. "They actually recognized when you should pet a dog and when you should not pet a dog."

But when put into a room with a real dog, those lessons went out the window. In fact, the researchers reported in December 2011 in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology, all the kids got more bold in interacting with the dog, regardless of which computer game they'd played, possibly because nothing bad had happened the first time they played with a dog in the psychology lab.

The Blue Dog Trust funded the research, but had no involvement with the study or the reporting of the results.

Schwebel and his colleagues are now working on ways to improve the software program to boost kids' street smarts around dogs. It's not unusual for people, even adults, to understand hypothetically what they should do in a situation but do the opposite, he said.

"A lot of people know they shouldn't speed when they go down the highway," he said. "But that doesn't mean that they follow the speed limit."

For now, he added, the main take-away for parents is to supervise children around dogs, no matter how trusted the family pet. [10 Things You Didn't Know About Dogs]

"People assume their dogs are safe, and most dogs are safe most of the time," Schwebel said. "But it's hard for people to admit that their dog has the potential to bite, if provoked enough. Every dog, if provoked enough, will bite."

Schwebel hopes that a greater awareness of the risks of mixing dogs and children will help dogs as well as kids. "Dogs don't like to be stressed by children," he said, adding that a dog that bites may end up euthanized.

"I'd like to see dog safety get on the radar," Schwebel said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.