Deep Sea Expedition Probes Tectonic Plates

On a chilly November Saturday after Thanksgiving, a team of scientists departed Honolulu for a remote portion of the central Pacific Ocean on the research vessel R/V Marcus G. Langsethin search of clues that would help explain the rumbling of the Earth.

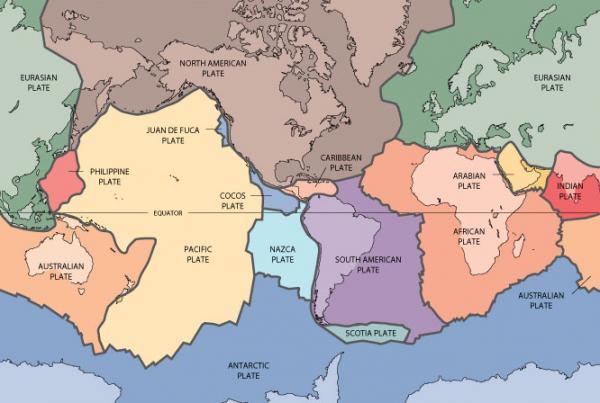

Their mission was to address very basic questions about the formation and evolution of oceanic tectonic plates, the jigsaw puzzle-like sections of the Earth's crust that move across the planet's surface and bump against each other, creating earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and new crustal rock.

The exact target of the mission was aswath of seafloor approximately 1,200 miles (1,900 kilometers) southeast of Hawaii where the ocean has an average depth of 16,700 feet(5,100 meters). According to one of the mission scientists, Jim Gaherty, this area was chosen because it contains some of the oldest oceanic crust on the planet and it has not been modified by other volcanic activity since it was formed 70 million years ago.

"We hope that the structure of this mature, pristine oceanic plate can illuminate the most basic aspects of plate formation and evolution," said Gaherty,a research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, who also blogged about the experience.

Sea sickness

The team of 13 scientists and 34 crew members faced some challenges on their initial voyage. Research ships travel at 10 knots (a whopping 12 mph) and the first few days were filled with sickness as the researchers adjusted to large rolling waves and strong winds.

Four days after departing Honolulu, they began deploying ocean-bottom seismometers and seafloor magneto-telluric instruments over a grid spanning 360 by 250 miles (580 by 400 km). The instruments measure natural electrical fields and magnetic fields simultaneously.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These fields can be used to infer the conductivity structure of the rocks at depth. The combination of seismic velocity and electrical conductivity are very useful for determining the composition, temperature and melt content of the rocks that make up the plate; these, in turn, allow us to better understand the evolution of the plate," Gaherty told OurAmazingPlanet.

Tight schedule

Living and doing science aboard the research vessel requires a very tight schedule and a round-the-clock attitude. "The ship is expensive to operate, so we don't want to waste any time," Gaherty said.

The team splits up into 12-hour shifts to make sure the instruments are deployed and data are collected properly. "Some days are extremely busy —we deployed 17 seismometers in one 12-hour shift," he said. Other days are spent finishing work that has been neglected from their jobs back on land.

The month-long voyage was just the beginning of the project to delve deep into the ocean's plates. Gaherty predicts the team will spend the better part of the next year carefully analyzing this data, producing images of the subsurface and then integrating the data from ocean-bottom seismometers.

"Based on those results, we will then think about what we have learned about plate evolution, what more questions still need to be answered, and how and where we need to go to answer those questions,"Gaherty said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.