Amazing Astronomy Illustrations From the 1800s Resurface Online

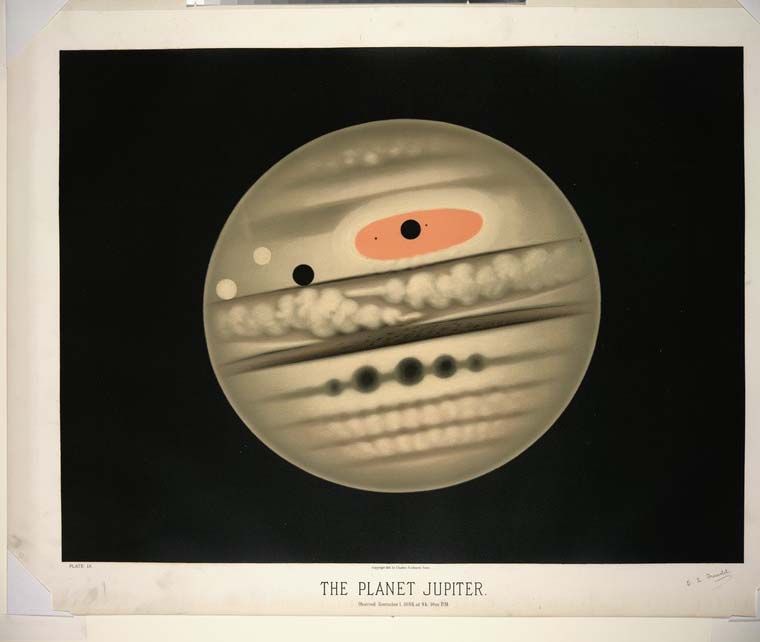

Recently digitized drawings by a 19th-century artist reveal stunning sunspots, auroras and even planetary bodies as they were observed in the Victorian era.

Recently digitized and made available by the New York Public Library, the images are a remarkably modern-looking glimpse into astronomy in the late 1800s. Drawn by French-born artist Etienne Leopold Trouvelot (1827-1895), the illustrations range from detailed surface studies of the moon to likenesses of the planets that could pass for pop art.

One drawing reveals the Great Comet of 1881 as seen in June of that year. Thanks to advances in photography, that comet was the first photographed clearly with both head and tail, according to a 1999 article in the Irish Astronomical Journal. Another details a meteor shower that lit up the skies one night in November 1868. [See Trouvelot's Astronomy Illustrations]

Trouvelot himself is less well-known for his astronomical art as he is for his earlier hobby as an amateur entomologist. In an attempt to improve silk production in the United States, Trouvelot imported the gypsy moths from Europe. Some larvae escaped, resulting in an invasive species disaster. Today, gypsy moths are still a devastating pest, consuming forest foliage in the northeastern United States and parts of the Southeast and Midwest.

Trouvelot tried to warn entomologists about the gypsy moth introduction, according to the U.S. Forest Service, but nothing was done. He then moved on to astronomical illustration and an eventual faculty post at Harvard University. A crater on Mars bears his name.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.