Field Trip: Exotic Yeasts, Frozen in Time

Budding with Potential

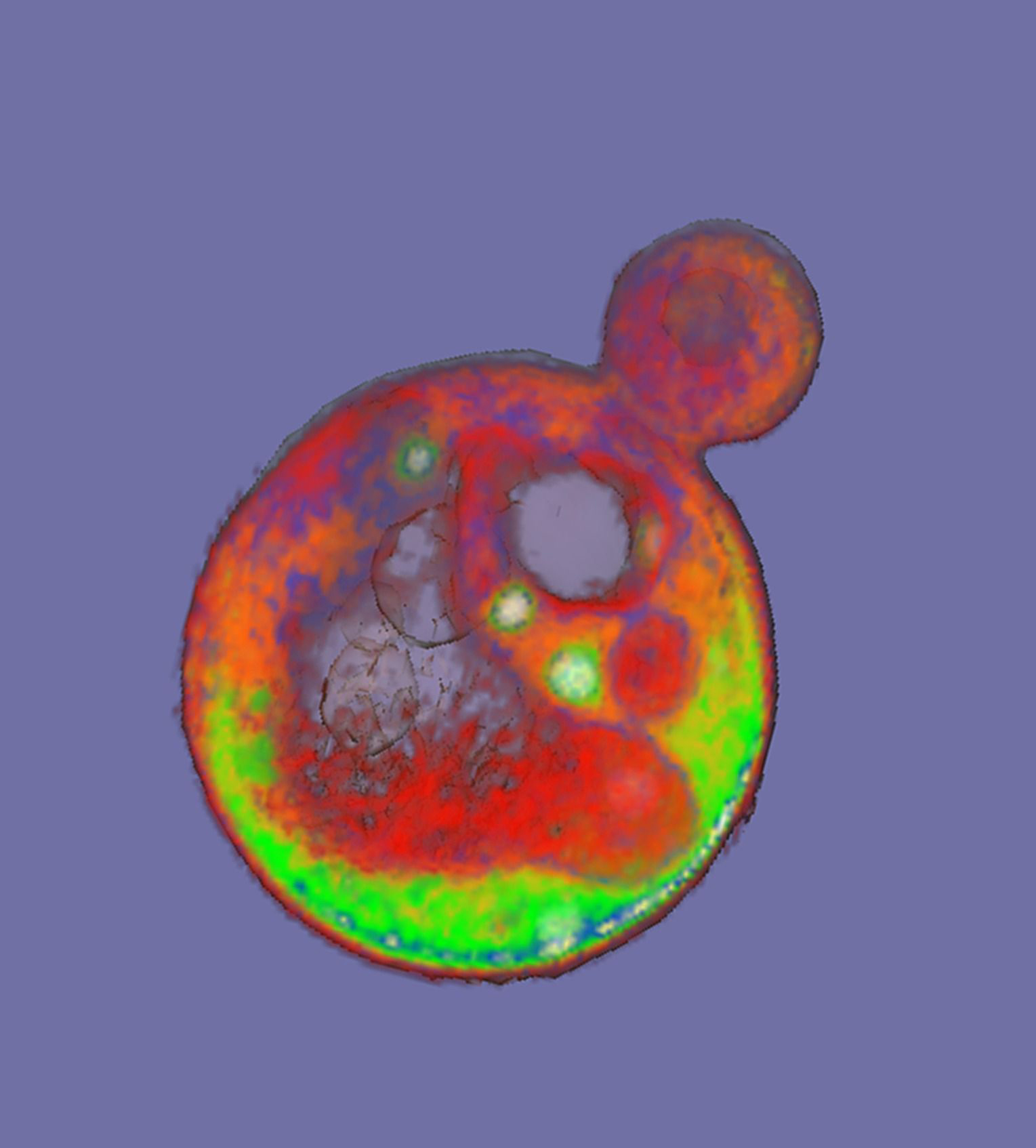

Yeasts are everywhere. The fourth largest public collection of wild yeasts, located at the University of California, Davis, has strains of the single-celled fungi collected from Antarctic seawater, hot springs, fruit, food processing facilities, air, macaroni, a horse's tumor, human cerebrospinal fluid and dandruff. They are the reason we can brew alcohol and they may hold the potential for better biofuels and drugs. And, under the right microscope, they can be quite beautiful. The image above shows a yeast cell in the process of budding, a form of reproduction.

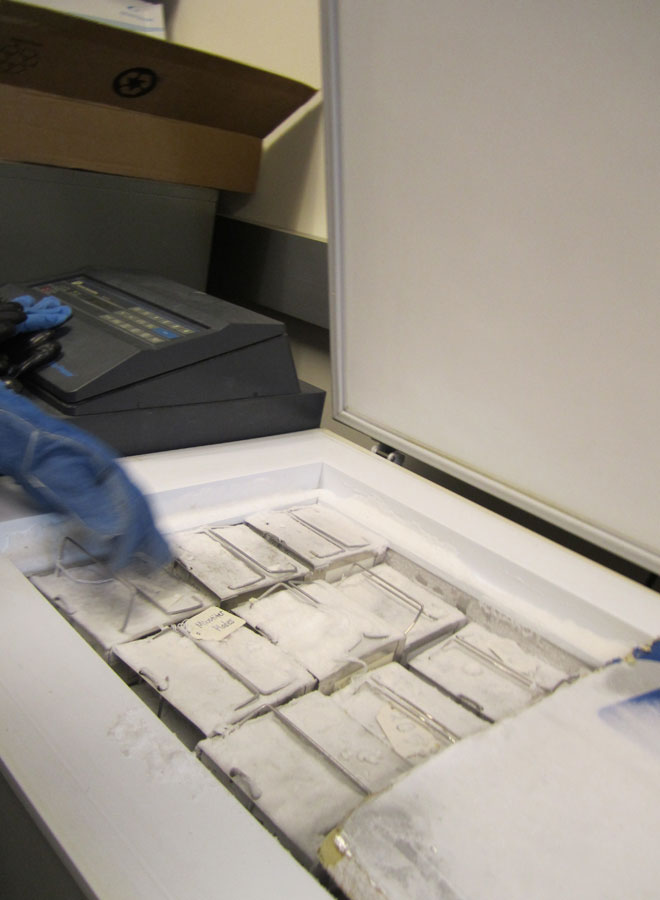

A Frozen Home

The Phaff Yeast Culture Collection at the University of California, Davis, houses more than 10,000 strains of microbes, most of them yeast, kept dormant at -112 degrees Fahrenheit (-80 degrees Celsius). Just in case, two freezers each house a complete set of the collection. A third set will be sent to Colorado as an emergency back-up.

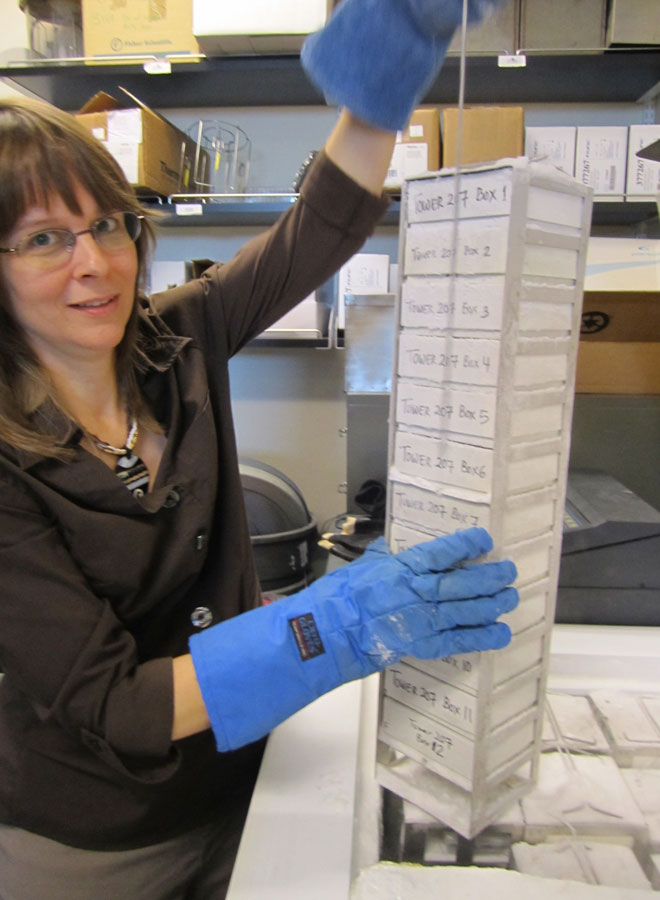

The Collection

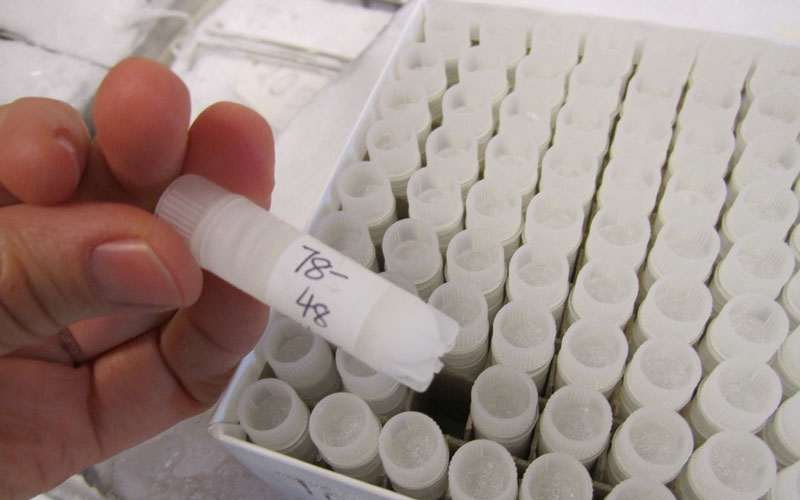

Each box contains 81 vials, each vial contains a single strain of yeast. Curator Kyria Boundy-Mills checks each vial every five years to make sure there are still enough live cells inside. She is an enthusiastic ambassador for the fungi: "I've got the greatest job in the world."

Frozen in Time

The cold temperatures keep the yeast dormant. The oldest strains in the collection are more than a century old.

Old Fashioned Yeast

Before the yeasts were put into freezers, they were preserved like this, in glass test tubes under mineral oil, with a piece of cotton to allow oxygen in and keep other fungi out. Boundy-Mills keeps some of the old ones around for show.

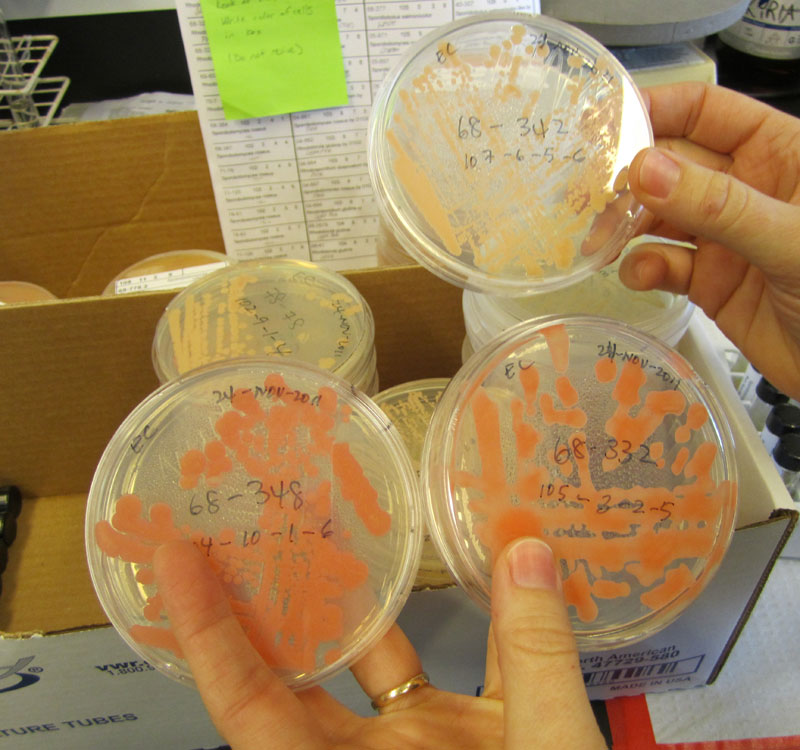

A Rainbow of Yeasts

Boundy-Mills grows yeasts from the freezers on Petri dishes like these to send out to other researchers. These yeast colonies come in many hues.The first two digits written on the dishes represent the year this strain was collected.

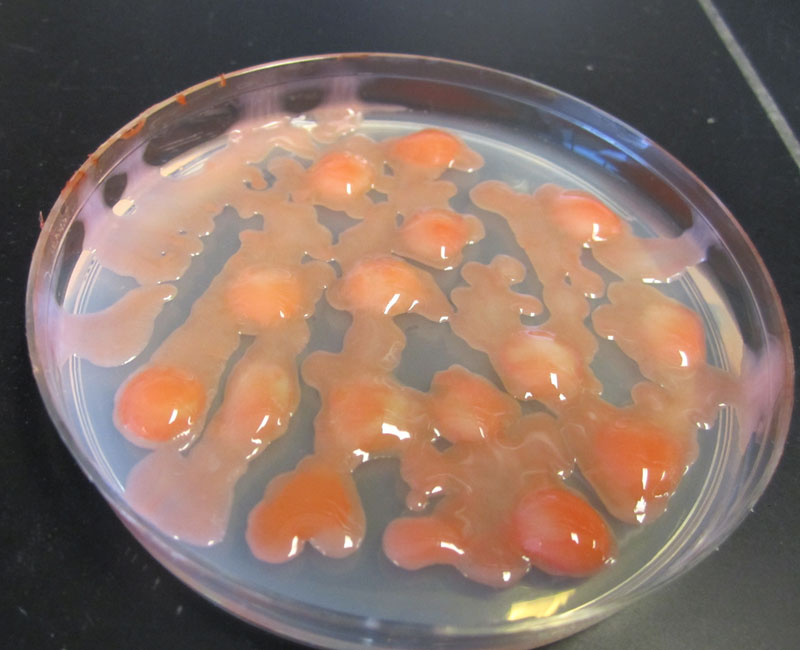

Lumpy Yeast

A particularly lumpy, or mucinoid, yeast. Herman Phaff, the collection's namesake, collected this yeast from insect frass (or poop) from a tree in British Columbia, in 1968.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Beetles & Biofuels

Boundy-Mill's work can take her far from the collection. She is heading up a National Institutes of Health-funded biodiversity survey that is looking for microbes with potential to improve biofuels or develop drugs. One unlikely place they look: The guts of wood-eating beetle larvae, like the dissected Buprestid beetle larva shown above.

The Grown-Up Version

An adult version of the Buprestid beetle, caught near the trees where the larvae were collected. The researchers need the adult versions of the larvae from which they collect microbes so they can identify the species of beetle.

Biodiversity Legwork

The work area for the biodiversity research at Papalia Protected Forest in Indonesia. This is where researchers assigned ID numbers to each larva and filled out paperwork.

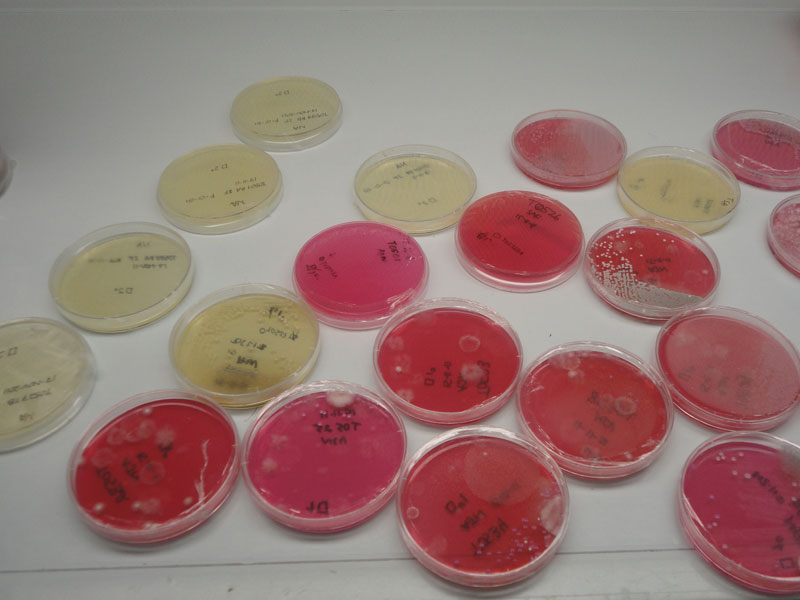

Microbes with Potential

Microbes grown from beetle larva guts in Petri plates at Universitas Haluo Oleo in Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. The researchers are looking not only for yeast, but also promising molds and bacteria.