Mysterious 'Winged' Structure from Ancient Rome Discovered

A recently discovered mysterious "winged" structure in England, which in the Roman period may have been used as a temple, presents a puzzle for archaeologists, who say the building has no known parallels.

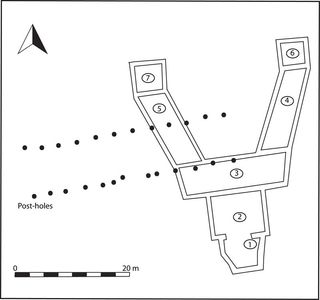

Built around 1,800 years ago, the structure was discovered in Norfolk, in eastern England, just to the south of the ancient town of Venta Icenorum. The structure has two wings radiating out from a rectangular room that in turn leads to a central room.

"Generally speaking, [during] the Roman Empire people built within a fixed repertoire of architectural forms," said William Bowden, a professor at the University of Nottingham, who reported the find in the most recent edition of the Journal of Roman Archaeology. The investigation was carried out in conjunction with the Norfolk Archaeological and Historical Research Group.

The winged shape of the building appears to be unique in the Roman Empire, with no other example known. "It's very unusual to find a building like this where you have no known parallels for it," Bowden told LiveScience. "What they were trying to achieve by using this design is really very difficult to say."

The building appears to have been part of a complex that includes a villa to the north and at least two other structures to the northeast and northwest. An aerial photograph suggests the existence of an oval or polygonal building with an apse located to the east.

The winged building

The foundation of the two wings and the rectangular room was made of a thin layer of rammed clay and chalk. "This suggests that the superstructure of much of the building was quite light, probably timber and clay-lump walls with a thatched roof," writes Bowden. This raises the possibility that the building was not intended to be used long term. [Photos of Mysterious Stone Structures]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The central room, on the other hand, was made of stronger stuff, with its foundations crafted from lime mortar mixed with clay and small pieces of flint and brick. That section likely had a tiled roof. "Roman tiles are very large things, they’re very heavy," Bowden said.

Sometime after the demise of this wing-shaped structure, another building, this one decorated, was built over it. Archaeologists found post holes from it with painted wall plaster inside.

Bowden said few artifacts were found at the site and none that could be linked to the winged structure with certainty. A plough had ripped through the site at some point, scattering debris. Also, metal detecting is a major problem in the Norfolk area, with people using metal detectors to locate and confiscate materials, something that may have happened at this site.

Still, even when the team found undisturbed layers, there was little in the way of artifacts. "This could suggest that it [the winged building] wasn't used for a very particularly long time," Bowden said.

The land of the Iceni

Researchers are not certain what the building was used for. While its elevated position made it visible from the town of Venta Icenorum, the foundations of the radiating wings are weak. "It's possible that this was a temporary building constructed for a single event or ceremony, which might account for its insubstantial construction,' writes Bowden in the journal article.

"Alternatively the building may represent a shrine or temple on a hilltop close to a Roman road, visible from the road as well as from the town."

Adding another layer to this mystery is the ancient history of Norfolk, where the structure was found.

The local people in the area, who lived here before the Roman conquest, were known as the Iceni. It may have been their descendents who lived at the site and constructed the winged building.

Iceni architecture was quite simple and, as Bowden explained, not as elaborate as this. On the other hand, their religion was intertwined with nature, something which may help explain the wind-blown location of the site. "Iceni gods, pre-Roman gods, tend to be associated with the natural sites: the springs, trees, sacred groves, this kind of thing," said Bowden.

The history between the Iceni and the Romans is a violent one. In A.D. 43, when the Romans, under Emperor Claudius, invaded Britain, they encountered fierce resistance from them. After a failed revolt in A.D. 47 they became a client kingdom of the empire, with Prasutagus as their leader. When he died, around A.D. 60, the Romans tried to finish the subjugation, in brutal fashion.

"First, his [Prasutagus'] wife Boudicea was scourged, and his daughters outraged. All the chief men of the Iceni, as if Rome had received the whole country as a gift, were stripped of their ancestral possessions, and the king's relatives were made slaves," wrote Tacitus, a Roman writer in The Annals. (From the book, "Complete Works of Tacitus," 1942, edited for the Perseus Digital Library.)

This led Boudicea (more commonly spelled Boudicca) to form an army and lead a revolt against the Romans. At first she was successful, defeating Roman military units and even sacking Londinium. In the end the Romans rallied and defeated her at the Battle of Watling Street. With the Roman victory the rebellion came to an end, and a town named Venta Icenorumwas eventually set up on their land. [Top 12 Warrior Moms in History]

"The Iceni vanish from history effectively after the Boudicca revolt in [A.D.] 60-61," said Bowden.

But while they vanished from written history, archaeological clues hint that their spirit remained very much alive. Bowden and David Mattingly, an archaeologist at the University of Leicester, both point out that the area has a low number of villas compared with elsewhere in Britain, suggesting the people continued to resist Roman culture long after Boudicca's failed revolt.

This lack of villas, along with problems attracting people to Roman settlements in the area, "can be read as a transcript of resistant adaption and rejection of Roman norms," writes Mattingly in his book "An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire" (Penguin Books, 2007).

There is "still a fairly strong local identity," said Bowden, who cautioned that while local people may have lived at the complex, the winged building is out of character for both Roman and Iceni architectural styles, a fact that leaves his team with a mystery.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.