Winged Dinosaur Wore Plumage of Black Feathers

The raven-size creature long thought of as the earliest bird, Archaeopteryx, may have been adorned with black feathers, researchers have found.

The structures that held the black pigment may have strengthened wing feathers, perhaps helping Archaeopteryx fly, scientists added.

Archaeopteryx lived about 150 million years ago in what is now Bavaria in Germany. First unearthed 150 years ago, the fossil of this carnivore, with its blend of avian and reptilian features, seemed an iconic evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds.

One recent study has called into question whether Archaeopteryx was a true bird or just one of many birdlike dinosaurs. To learn more about whether birds and birdlike dinosaurs might have evolved flight, and if so, why, researchers often turn to the animals' feathers. Illustrations of the creature are often colorful, but such depictions of its plumage until now had little else but artistic license to draw on.

"Being able to reconstruct the colors of feathers can help us gain more knowledge about the organisms and more responsibly reconstruct what they looked like," researcher Ryan Carney, an evolutionary biologist at Brown University, told LiveScience.

Black feathers

An international team of scientists now finds that a well-preserved feather on Archaeopteryx's wing was black. The color-generating structures within the creature's feather, known as melanosomes, "would have given the feathers additional structural support," Carney said. "This would have been advantageous during this early evolutionary stage of dinosaur flight." [Images: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

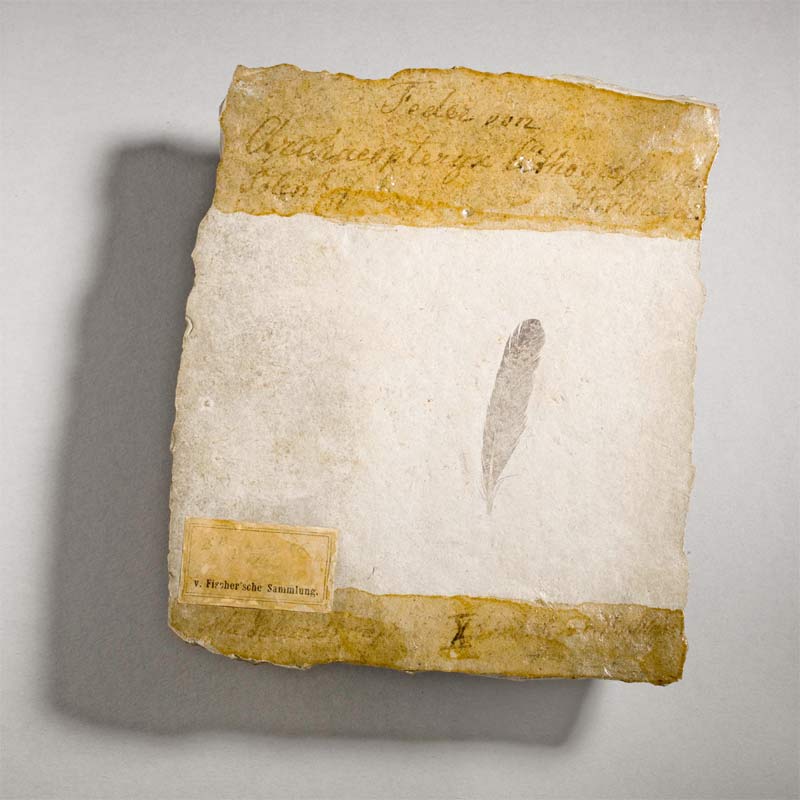

The Archaeopteryx feather was discovered in a limestone deposit in Germany in 1861. After two unsuccessful attempts to pinpoint any melanosomes within the feather, the investigators tried a more powerful type of scanning electron microscope.

"The third time was the charm, and we finally found the keys to unlocking the feather's original color, hidden in the rock for the past 150 million years," Carney said.

The group located patches of hundreds of melanosomes encased within the fossil. The sausage-shape melanosomes were about 1 millionth of a meter long and 250 billionths of a meter wide — that is, about one-hundredth the diameter of a human hair in length and less than a wavelength of visible light in width. To determine the color of these melanosomes, researchers compared the fossilized structures with those found in 87 species of living birds that represented four classes of feathers — black, gray, brown and ones found in penguins, which have unusually large melanosomes compared with other birds.

"What we found was that the feather was predicted to be black with 95 percent certainty," Carney said.

Did Archaeopteryx fly?

To better pin down the structure of the feather, they analyzed its barbules — tiny, riblike appendages that overlap and interlock like zippers to give a feather rigidity and strength. The barbules and the way melanosomes are lined up within them are identical to those found in modern birds, Carney said.

This analysis revealed the feather is a covert, one that covers the primary wing feathers that birds use in flight. Its feather structure is identical to that of living birds, suggesting "that completely modern bird feathers evolved as early as 150 million years ago," Carney said.

Color may serve many functions in modern birds, and it remains unclear what use or uses this pigment had in Archaeopteryx. Black feathers may have helped the creature absorb sunlight for heat, acted as camouflage, served in courtship displays or assisted with flight.

"We can't say it's proof that Archaeopteryx was a flier, but what we can say is that in modern bird feathers, these melanosomes provide additional strength and resistance to abrasion from flight, which is why wing feathers and their tips are the most likely areas to be pigmented," Carney said. "With Archaeopteryx, as with birds today, the melanosomes we found would have provided similar structural advantages, regardless of whether the pigmentation initially evolved for another purpose."

More feathers will need to be tested across Archaeopteryx to see how the animal was colored overall, researchers said. Unfortunately, this is the only Archaeopteryx feather discovered with the kind of residues one can test for color.

Still, this one feather is enough to leave an indelible mark on Carney. "I got a tattoo of the feather on the 150th anniversary that Archaeopteryx's scientific name was published," he said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Jan. 24) in the journal Nature Communications. Their work was funded by the National Geographic Society and the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Follow Live Science for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.