New Vaccine Approach Gives Hope to Those Living with HIV

Brian Brown has been taking antiretroviral drugs for five years. If he stops, the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, in his body will multiply and eventually, he'll get really sick. "You have to take them with food," Brown said. "Even if you aren't really hungry." A 39-year-old licensed practical nurse, Brown has to remember to take his drugs daily. It's a routine familiar to people with all kinds of chronic diseases, including HIV and diabetes.

Brown got a break, though. In 2010, he was part of a study of a new kind of vaccine for HIV, called Vacc-4x, from a company called Bionor. He was able to stop taking his two drugs for almost two years. The vaccine didn't cure him, but it cut down the number of HIV viral particles in his body to nearly undetectable levels, and his immune system's virus-fighting cells, called T-cells, went up.

Vacc-4x is just one HIV treatment that illustrates a new approach to HIV vaccines that has gained increasing currency in the last few years. Most people think of vaccines as a preventative measure, and early efforts to control HIV were focused on that strategy. The problem is that even though some are promising, preventing infection doesn’t do any good for the 34 million people worldwide who are already infected. To stop the spread, the key might be a post-infection vaccine like those given for rabies.

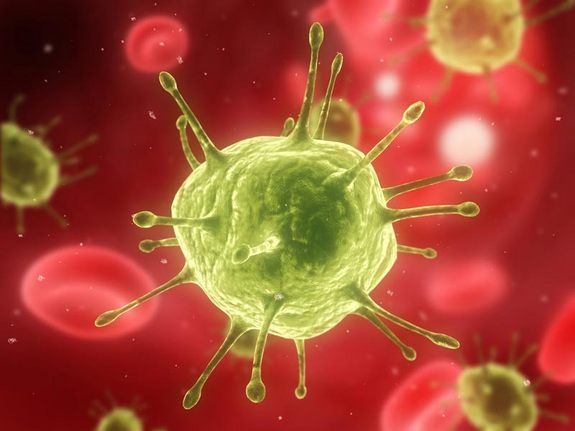

HIV, however, is a tough nut to crack. It attacks the very cells that detect and kill invading pathogens. Even when it isn't actively replicating, it can live in tissues in the nervous system or the gut for years. This is one reason HIV takes so long to manifest, and why the immune system has a tough time recognizing it and destroying infected cells. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Currently, the best way to treat HIV is with antiretroviral therapy — drugs that aim at keeping the levels of virus in a person's blood low. These drugs have extended life spans, allowing for normal lives and reducing the chances of transmitting the virus. However, the side effects can negatively affect health, bringing liver problems and nausea.

There is also the problem of sticking to the drug regimen. "Adherence is a challenging thing," said Frank Oldham, chief executive officer of the National Association of People With AIDS.

Enter: new HIV vaccines

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There are several therapeutic vaccines in development. Approaching HIV in slightly different ways, all are designed to allow the body's immune system to at least fight the virus to a standstill, and perhaps even keep it at undetectable levels. Common to all treatments is giving the immune system some way to recognize HIV. The vaccines differ in the markers (called antigens) they use to flag HIV particles, and in how they are delivered to the body.

Vacc-4x trains a person's immune system to recognize and fight a key protein that HIV relies on, called gp24. It also stimulates the production of white blood cells, which normally are killed by the virus. Early results show patients' viral loads coming down by a factor of three.

Genetic Immunity, a U.S.-Hungarian company, is testing a vaccine called DermaVir. Rather than focusing on a single protein, DermaVir uses a tiny bit of HIV DNA (called plasmid DNA) to generate a set of 15 chemical markers that the body's T-cells can recognize. The idea is to maximize the number of ways the immune cells can "see" the virus. The vaccine is administered by rubbing the skin enough to irritate it. Cells called dendritic cells will pick up a nanoparticle containing the DNA and deliver it to the lymph nodes, where the infection-fighting T-cells are generated.

The vaccine has been tested on about 70 patients so far and showed a 70 percent reduction in viral load, according to Genetic Immunity’s president, Dr. Julianna Lisziewicz. Another set of trials on patients is currently under way. [AIDS: A 'Winnable' Public Health Battle?]

Another approach is being taken by Gaithersburg, Md.-based company VIRxSYS, which uses a genetically altered HIV virus to deliver the vaccine. The body doesn't recognize HIV easily, and thus won't mount an immune response to the very vehicle delivering the medicine, said Franck Lemiale, senior director of immunobiology at the company.

To make sure that the T-cells will "see" many strains of HIV, the VIRxSYS vaccine uses proteins called Gag, Pol and Rev, which tend to be the same in all of variations of the HIV virus.

The company said in July 2011 that a version of its vaccine tested in monkeys, called VRX1273, had not only brought the viral loads down to undetectable levels in body fluids, but in tissues as well. If that result can be duplicated in humans, it might mean that the vaccine is helping the body to eliminate the virus entirely.

Vaccine vectors

Other groups are trying different delivery modes, or vectors. Dr. Chil-Yong Kang, a virologist at the University of Western Ontario, heads up a lab whose preventative vaccine, after receiving FDA approval in December, will go into trials designed to determine the safety of the vaccine. Kang hopes his vaccine, which would ride into the body on another virus, will also enable the body to attack infected cells in the tissues where HIV likes to hide.

Perhaps the most high-tech vaccine under development is from Argos Therapeutics, called AGS-004. Monocytes, a type of white blood cell, are taken from the patient, and artificially induced to become immature dendritic cells. Those cells are then exposed to the RNA (a molecule similar to DNA) of HIV particles taken from the patient until they produce antigens, red flags of sorts, to alert the immune system of the virus. Re-introduced to the patient, they can then bring the antigens to the T-cells, which then find and kill HIV.

Of the vaccines, Vacc-4x, Argos and Dermavir are closest to being approved for general use, with Vacc-4x having just finished phase 2 trials for efficacy in humans and Argos and Dermavir in phase 2b. That means all are seen as safe to use, have been tested in small groups, and will next be tested in large populations (phase 3). The others are either still being tested in animals or in the safety phases of testing.

"Clearly this field is young enough that we don't have a product that we can say is the greatest," said Dr. David M. Asmuth, co-director of the Clinical Research Center at the University of California, Davis, Medical Center, which administered the Vacc-4x to HIV patient Brown. While the trials have shown promise, he is still cautious.

Asmuth notes the Vacc-4x trial Brown was in showed a reduction in viral load. But it is still unclear how long that would last once the patients were off ART.

He also noted that HIV-positive individuals have a "set point" — a viral load that stabilizes after infection, and can remain stable for years. When people get sick, it is because the number of virus copies suddenly increases and the immune system is overwhelmed. The current crop of vaccines being tested may only change the set point to something lower. That is still a good thing, but it isn't a cure.

What would be ideal, Asmuth said, is a vaccine that reproduces what doctors see in people whose own bodies keep HIV under control for years, sometimes indefinitely. They are called "long-term non-progressors." Their viral loads should stay low and the CD4 count (a measure of immune health) should stay at 500-600, which is normal (a CD4 count less than 200 is often used as the diagnosis for AIDS). None of the vaccines being tested has shown they can do that — yet.

Even so, Asmuth is optimistic. "Who would have guessed 30 years ago that we would have the degree of control over the virus that we have now?"

Oldham said the fact that such therapies are in trials at all is exciting. "This would be a monumental breakthrough," he said. "Antiretrovirals were the beginning. I think therapeutic vaccines would be the next step towards improving lives."

Brown meanwhile, said the Vacc-4x trial meant many of the small routines he built up over years won't be necessary anymore — and small changes add up. "I didn't have to remember to take my pills," he said. "I could travel without having to think about bringing them."