What 'American Values' Really Means

American values. President Barack Obama wants to reclaim them. Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul wants to restore them. Newt Gingrich says he articulates them. Other presidential candidates, politicians and commentators have plenty to say about them as well.

But what exactly are they talking about? What are American values?

The answer: It depends.

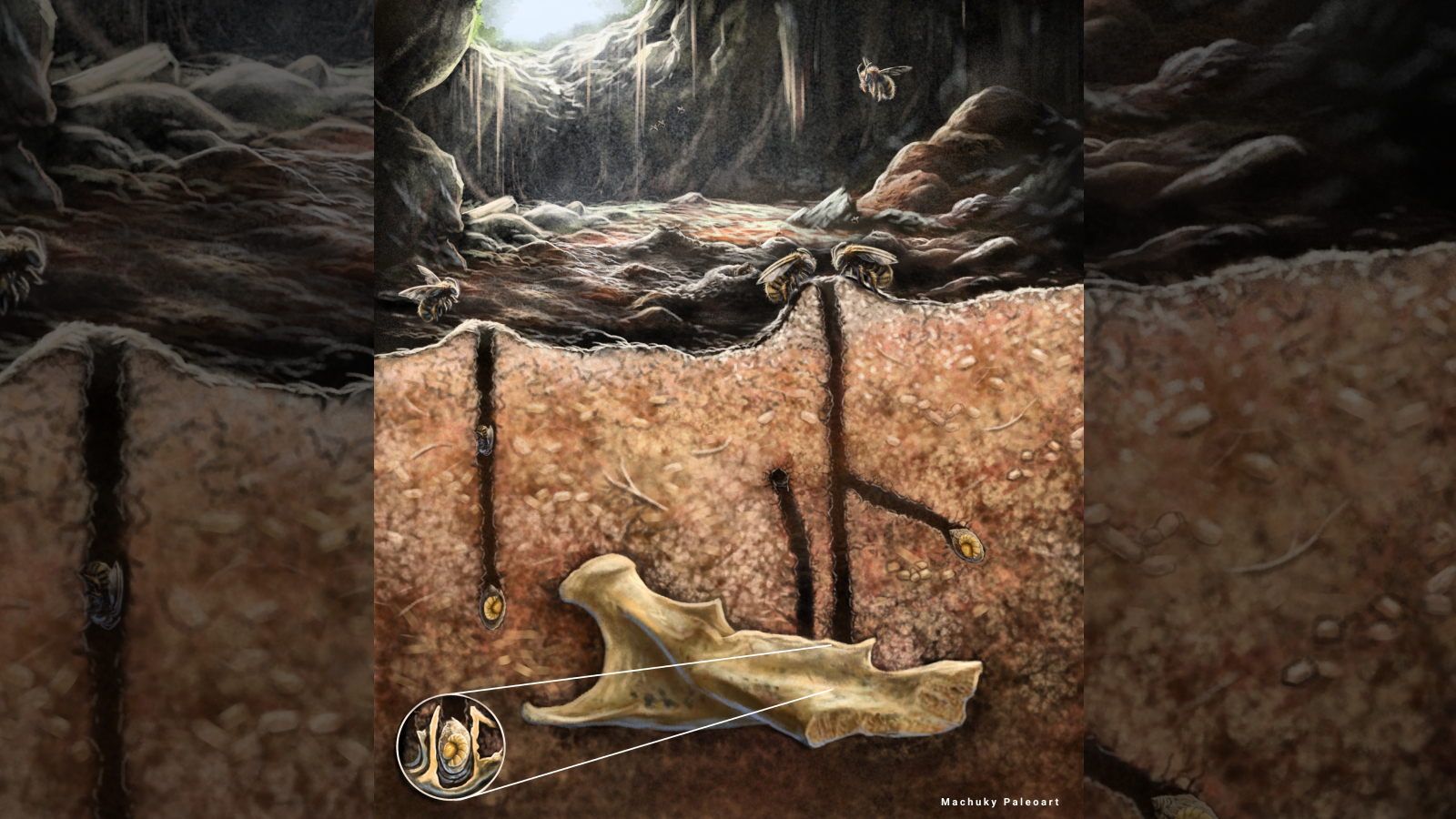

Vanessa Beasley, an associate professor in the department of communication studies at Vanderbilt University, compares the phrase, "American values" to a Rorschach test— in which a person looks for an image within symmetrical inkblots. The test prompts different people to see different things. [10 Mysteries of the Mind]

"It means whatever that group of constituents wants it to mean," she said.

After the State of the Union address, in which Obama called upon the nation to "reclaim" American values, LiveScience went looking for a common definition. Big surprise: We didn't find just one.

Depending on whom you ask, this phrase can offer insight into our national political rhetoric, as Beasley describes. It can also offer a window onto our collective psychology and help to explain characteristics of our society, according to some research that links values to economic systems.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Three out of four

In his State of the Union address, Obama talked of restoring "an economy where everyone gets a fair shot, everyone does their fair share and everyone plays by the same set of rules. What's at stake are not Democratic values or Republican values, but American values."

Meanwhile, Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum has spoken of "our values about faith and family," and fellow contender Mitt Romney has referred to the "American values of economic and political freedom."

All of these touch on aspects of the four primary interpretations of American values, only three of which are used today, according to Beasley.

The first is economic, the American dream: If you work hard, you will receive the fruits of your labor.

The second is religious or moral and traces back to our Puritan roots, and it has two competing varieties: We have freedom to worship and the right to object to religious intolerance; alternatively, the United States is a solely Christian nation.

The third is about individualism: We each have the ability to create our own fortune, the freedom to make our own choices.

The fourth, the one we don't hear much anymore, is what the country's founders called civic republicanism, the idea of making sacrifices — for example, going to war — for the common good. This version directly conflicts with individualism, Beasley points out.

With a wink

When invoking these national values, politicians don't get specific, typically leaving room for their audience to fill in its own perceived common references, Beasley said. Something similar happens with references to "freedom." It appears to be an ideal that unites us as Americans, unless we have a conversation about what it means. Then it may turn out one of us is talking about economic freedom, while the other is concerned with the pursuit of happiness, she said.

This catch-phrase tactic is increasingly a part of campaign rhetoric, in part because people are grouping themselves more with others who share their views and away from others who don't.

"If you are in a group of people who have the same beliefs that you have, you don't have to fill in the gaps," Beasley said.

The political right invokes the phrase "American values" more frequently than the left, an imbalance Beasley traces back to 1992, when former Vice President Dan Quayle addressed what he described as a decline in family values, such as the acceptance of unwed motherhood.

In his speech, President Obama was attempting to reclaim the phrase for the left, Beasley said. "I think Obama is trying to redefine American values within the economic context on grounds that resonate with working- and middle-class voters."

Two Americas

American values mean something different from a psychological perspective, with Tim Kasser, a professor of psychology at Knox College, uses a framework that includes places values according to how extrinsic or intrinsic they are. Extrinsic values, such as a desire for fame or wealth and material gain, are focused on earning rewards or praise and tend to be more self-oriented, while intrinsic values, like a desire for community, are more cooperative.

"The fact is that America has many things that are quite extrinsic, but also some things that are quite intrinsic as well," Kasser said.

For instance, in a study published in 2011 in the journal Ecopsychology, Kasser and others set out to speak to the extrinsic American character to some study subjects and the intrinsic national character of others. They did this by constructing brief profiles of the values associated with either side: The extrinsic side included a focus on wealth, financial success, material gain, competitiveness and "Hollywood ideals of beauty, celebrity and fame." The intrinsic description included generosity, willingness to pull together in times of need, self-expression, personal development and strong family values. [7 Thoughts That Are Bad For You]

A reflection of economics?

Research has shown that if a value on one end of the spectrum is primed, this causes people to suppress values on the other end of the spectrum, and alters their behavior. So, for example, a discussion of money or image can make people less helpful to others, he said.

His research indicates this phenomenon plays out a national scale, with roots in a country's economic system.

Research has shown that nations like the United States, which have economic systems that emphasize the power of the free market with limited regulation, citizens have a greater preference for extrinsic values than citizens of other wealthy nations with more coordinated economics, like those of the Scandinavian nations. (For the record, people in all of these countries rate intrinsic values as more important than extrinsic, but the gap narrows for nations with economic systems like ours.)

This extrinsic shift makes it difficult for citizens of the more free-market economies to care about the more pro-social, intrinsic values, because "it is relatively difficult to simultaneously care about the two sets of values," he said.

This has societal implications, according to Kasser. He has related the priority a nation places on more intrinsic values with better performance on a number of measures: children's well-being, more generous maternity-leave laws, less advertising directed at children, and lower carbon-dioxide emissions.

He points out that a 2007 report from the United Nations Children's Fund ranked the United States second to last for children's well-being among economically advanced nations, above only the United Kingdom.

"The point is that our economic organization … influences citizens' values. Those values end up influencing who we vote for and what policies are passed. Those policies and values, in turn, end up influencing how we treat each other and thus the well-being of children," he wrote in an email to LiveScience.