'Dead' Deep Sea Vents Teem with Life

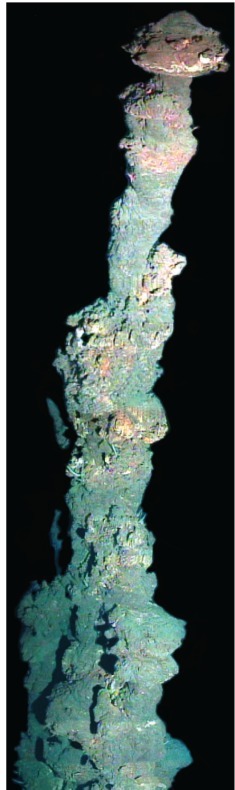

Volcanic seafloor vents that roar with the scalding heat of Earth's interior don't stay hot forever. Eventually, over hundreds or thousands of years, they flicker out and turn cold.

Yet new research reveals that the action on these oases of life on the seafloor doesn't stop when the heat goes off. Life goes on in the frigid dark, but on a teeny scale.

It turns out that large populations of bacteria live on expired vents, and these microbes are very different from those that thrive when the vents are piping hot, according to a study published this week in the journal mBio.

Scientists found evidence that up to 2,000 different sorts of microbes were living in a small section of a long-expired vent near the East Pacific Rise, a vast seam on the seafloor in the southern Pacific Ocean where two tectonic plates are being wrenched apart. For comparison, up to 8,000 varieties of microbes have been found living on active, hot vents, and up to 10,000 in deep seawater.

Although finding the microbes themselves didn't come as a huge shock — scientists have found bacteria living in other types of cool seafloor rocks — the revelation of who exactly moved in once the vents went cold was surprising, according to the study authors.

"Seeing the shift in the microbial population — seeing who actually came and left was fairly illuminating for me," said study co-author and geomicrobiologist Katrina Edwards, a professor at the University of Southern California.

Who's there?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The samples from the East Pacific Rise vents revealed a world of bizarre biological harmony. Microorganisms that employ utterly different physiological mechanisms to survive were living almost side by side.

In other samples of seafloor rock, the microbe communities typically change gradually, shifting in a way that brings to mind a road trip across an entire country, "whereas here, it's like there are different neighborhoods, and they can change pretty drastically," said Jason Sylvan, a USC post-doctoral researcher and lead author on the paper.

Gated communities of anaerobic organisms (which don't need oxygen to survive) were parked next to gated communities of aerobic organisms, which do require oxygen.

"Finding things that are anaerobic and aerobic right next to each other was surprising," Sylvan told OurAmazingPlanet.

A living arrangement akin to a golden retriever and a trout living across the hall?

"It's probably more drastic than that, but that's the right idea," Sylvan said.

Big effects

Overall, Edwards said, the research highlights how little we know about the sheer abundance of life on the seafloor, which has implications for understanding large-scale planetary processes.

Both scientists emphasized that the deep ocean increasingly appears to play a huge role in the way carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change, is processed by the planet's interlocking systems of atmosphere, land and ocean.

"There are all these organisms down there making biomass, and that's not accounted for in our carbon cycle at all," Edwards told OurAmazingPlanet. "The ocean floor is quite vast so there is an opportunity for these organisms to have an effect."

The research comes on the heels of splashy news from deep sea vents around the world.

Scientists recently announced the discovery of ghostly white yeti crabs swarming newfound vents near Antarctica, and bizarre shrimp with eye-like features on their backs that thrive on the deepest vents ever discovered on Earth.

Sylvan said the cold, expired vents deserve attention, too.

"When we think of hydrothermal vents we think of things that are really exciting, like hot, black smoker ventsor big animals," he said, "but there are also exciting things happening that aren't necessarily visible to the naked eye."

- Gallery: Unique Life at Antarctic Deep-Sea Vents

- Earth's Final Frontier: Mysteries of the Deep Sea

- In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.