Gallery: Peek Inside a Coral Nursery

Growing & Protecting Coral

Our oceans' coral reefs faces many threats, including damage caused by shipping vessels, severe storms, earthquakes, plankton blooms, disease, pollution, predators, overfishing and coral bleaching, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

However, man-made coral nurseries like the one featured in this gallery are aiming to help coral populations rebound and thrive.

Read on to see how precious coral is grown and cared for before being moved to their final home on a natural reef.

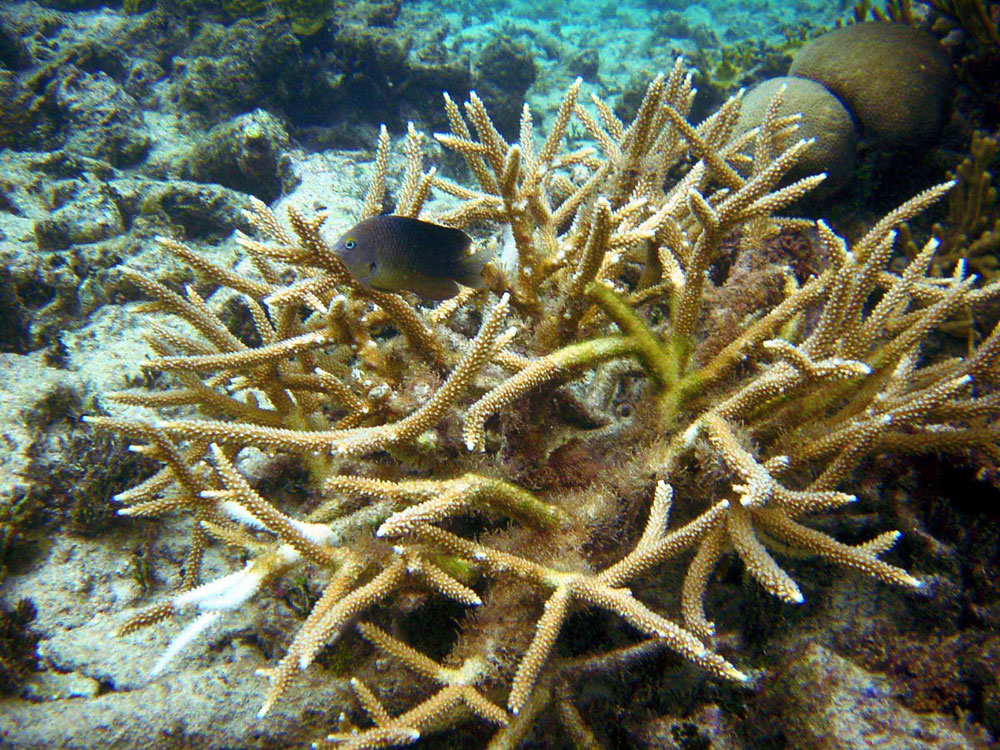

Staghorn Coral

Researchers and volunteers at The Nature Conservancy (TNC), an organization focused on ecological conservation around the world, are working to help staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) populations grow.

Staghorn coral gets its name from its beautiful formation, which resembles the antlers of male deer. These "antlers" grow remarkably fast, increasing in length by about 4 to 8 inches (10 – 20 centimeters) a year; as such, the staghorn coral plays an important role in the development of coral reefs and habitats for fish and other marine life.

Despite its rapid growth, staghorn coral is listed as federally threatened under the Endangered Species Act, according to the National Park Service.

As part of the "Threatened Coral Recovery in Florida and the U.S. Virgin Islands" project, TNC is monitoring more than a dozen coral nurseries that have been installed and are being maintained by several other organizations, including Nova Southeastern University, University of Miami, Coral Restoration Foundation, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and Mote Marine Laboratory. Funding for this project was made available through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

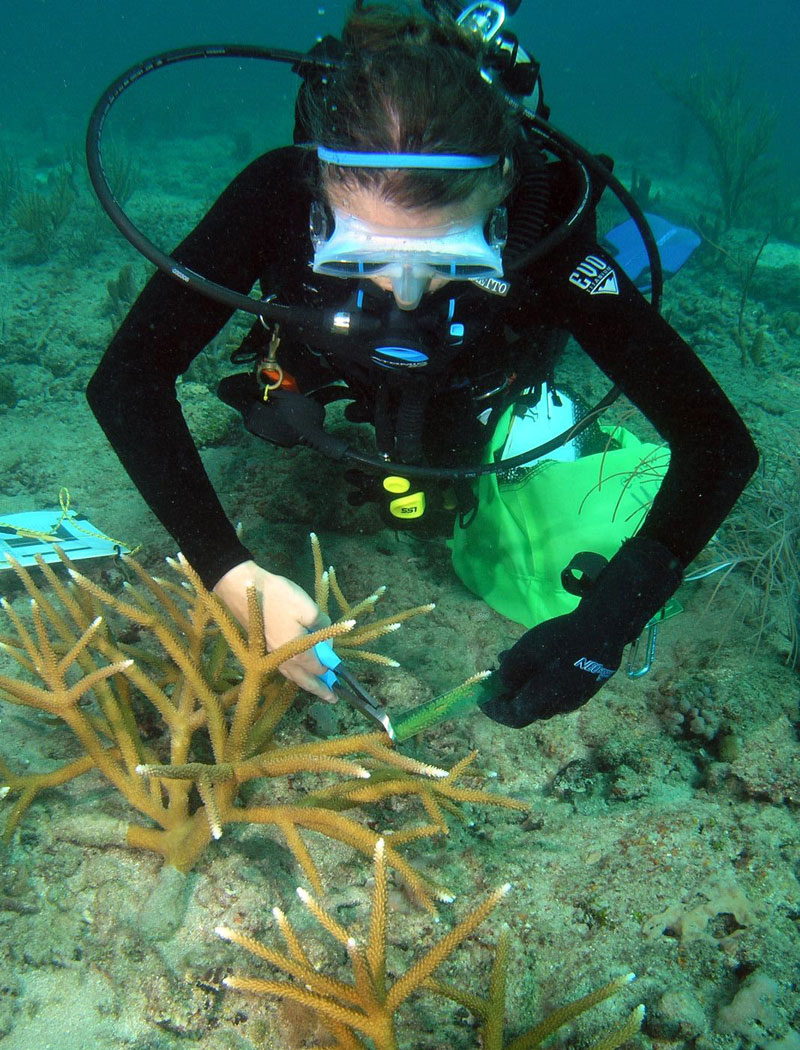

Clipping the "Horns"

First, researchers carefully measure and clip off tissue from healthy staghorn coral growing in the wild. These fragments are then brought into of TNC's 14 nurseries to be propagated.

Most of these nurseries exclusively grow staghorn coral, although six of the nurseries also grow elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata).

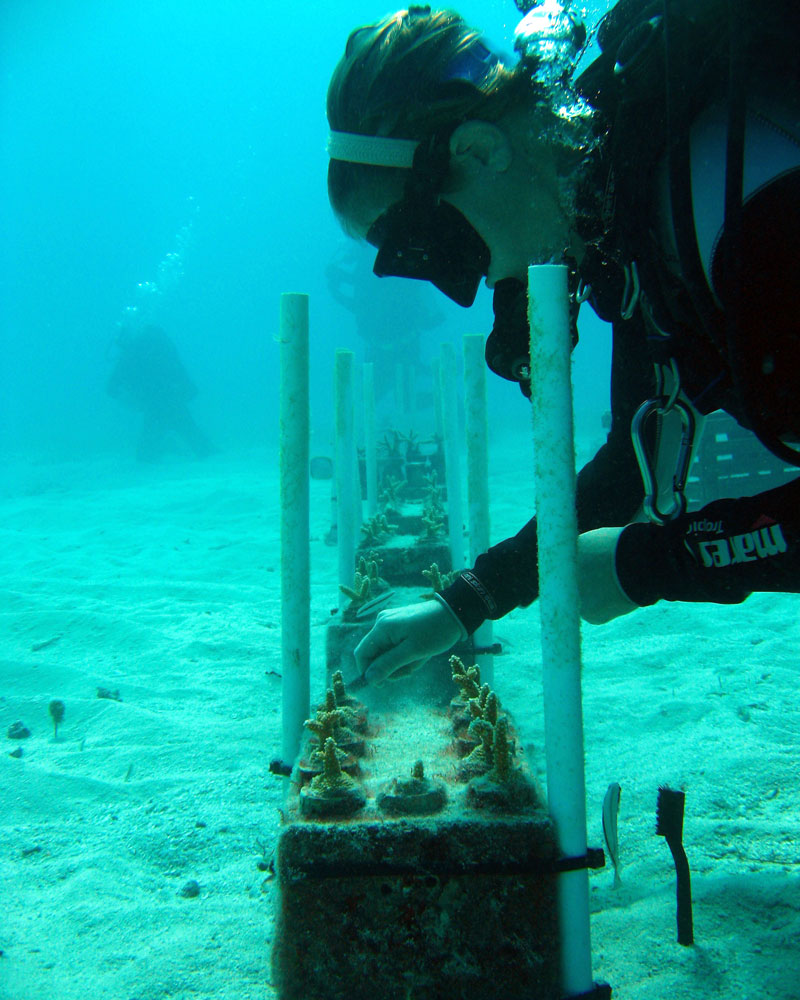

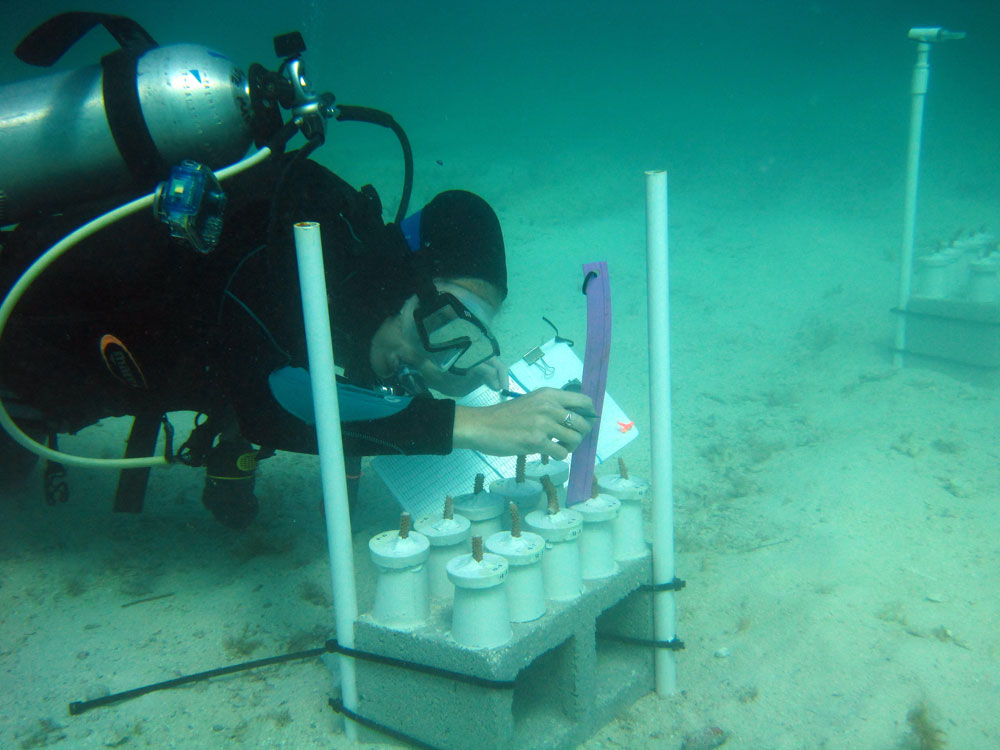

Planted on Pucks

In the traditional "block" nurseries, the researchers use underwater epoxy adhesive to attach the collected pinkie-size coral fragments to small concrete disks called pucks. These disks can then be fastened to pedestal blocks to lift the coral higher and closer to the light.

Planted on Pucks

In the traditional "block" nurseries, the researchers use underwater epoxy adhesive to attach the collected pinkie-size coral fragments to small concrete disks called pucks. These disks can then be fastened to pedestal blocks to lift the coral higher and closer to the light.

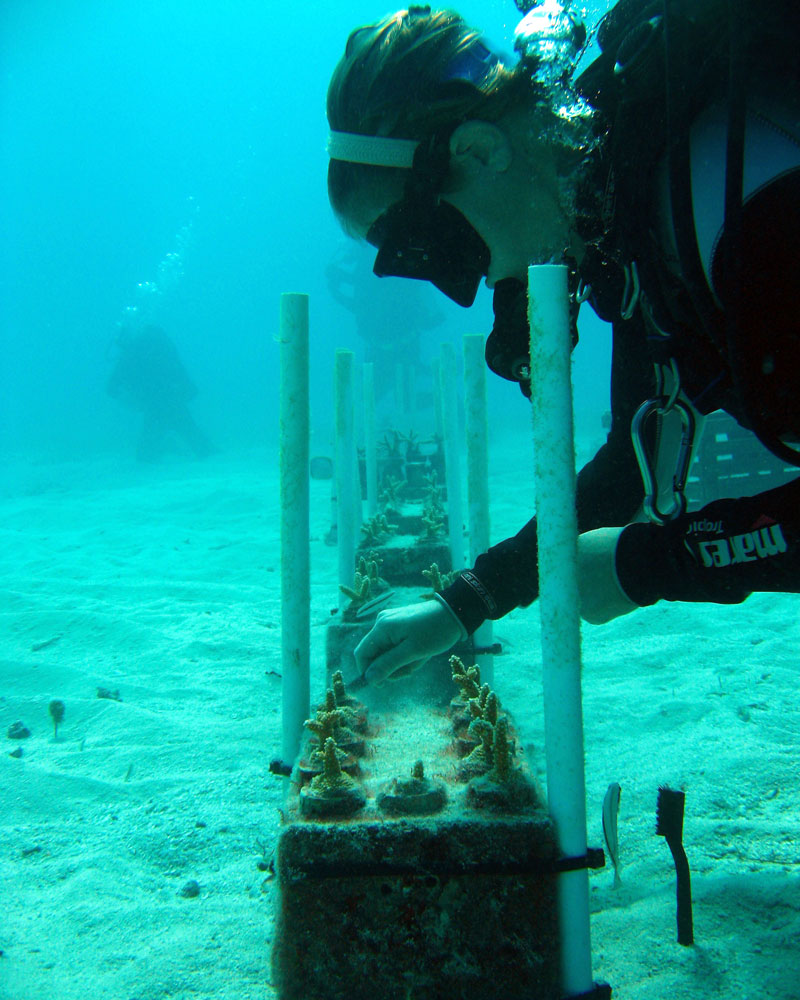

Growing Tall

A healthy staghorn coral fragment grows on a concrete puck. Researchers wait for the coral to reach a certain size before it can be "outplanted," or transferred to a natural reef environment.

"Our guidance is that a staghorn coral must be 5 centimeters in length to be outplanted, and an elkhorn coral must be at least 5 centimeters in diameter," Caitlin Lustic, a coral recovery coordinator at TNC, told LiveScience.

"We start with a 3-centimenter fragment of coral and then let it grow and create new corals through fragmentation," she said.

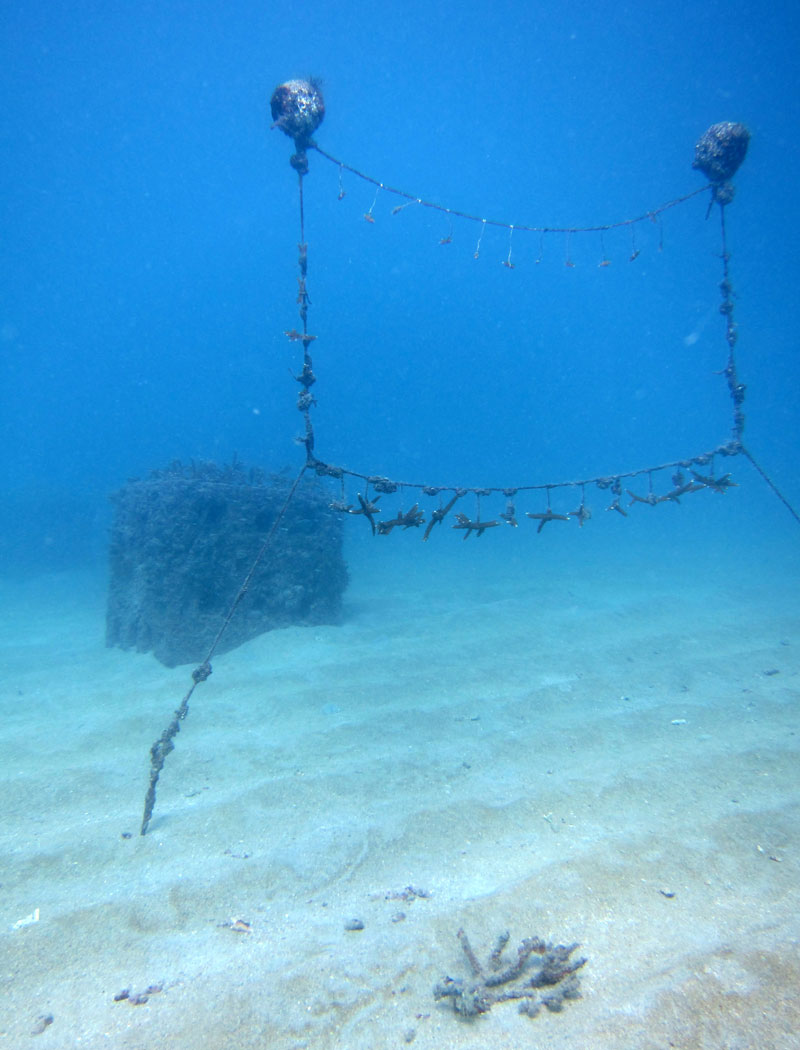

On the Line

In total, the 14 TNC nurseries are home to about 28,000 coral fragments.

The growth rate of a coral fragment depends on its genotype and the nursery method used to cultivate it. For example, the fragments can also be grown hanging from a line or strung from a "tree" fixture underwater.

This photograph shows coral fragments developing on a line nursery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A New Approach

This amazing shot shows staghorn coral fragments hanging on a "tree" nursery, which is a new design that was piloted as part of the TNC's coral growth project.

Tracking New Growth

As the coral fragments develop, they are regularly measured as part of the nurseries' monitoring protocol.

Cleaning the Coral

At the nurseries, the coral fragments are also regularly cleaned to prevent harmful algae growth, which can smother young corals (Read related article: Seaweed Wages Chemical Warfare Against Corals). Even after the coral fragments are outplanted, researchers will continue to monitor and maintain the corals to make sure that they remain healthy and continue to grow.

Ready to Go

These staghorn coral fragments are ready to be outplanted back to natural reefs. It's a tough underwater world out there, but the researchers will do all they can to help the young corals adjust.

"In the first year, it is common for them to experience predation and breakage," Lustic said. "To counteract this, some predators will be removed from the corals and broken pieces will be epoxied to the substrate."

The organization and its collaborators are currently working on outplanting the fragments, and estimate that they will outplant at least 5,000 corals to at least 34 different reef sites.

Outplant sites are selected based on which habitat area is capable of supporting healthy colonies. An area's existing wild coral populations are also taken into consideration, since one main goal of the project is to increase genetic diversity in natural coral reefs.