Our Planet's Killer Electrons Shoot Toward Space, Not Earth

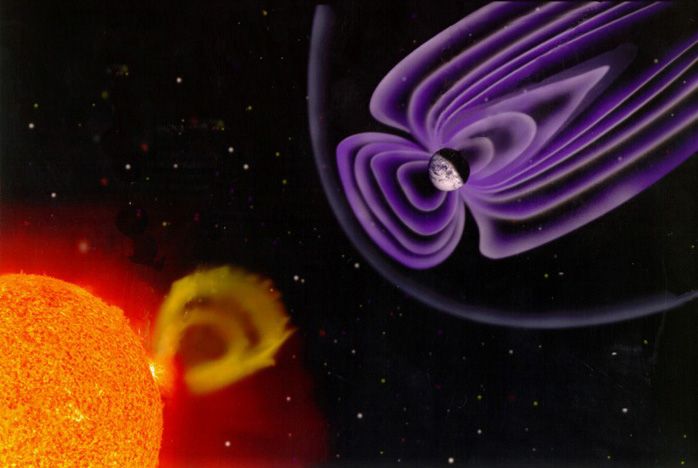

As the sun heads toward its 2013 maximum, the corresponding increase in space weather may temporarily strip the radiation belts around Earth of their charged electrons. But a new study of data recorded by 11 independent spacecraft reveals that the deadly particles are blown into space rather than cast into our planet's atmosphere, as some scientists have suggested.

Streams of highly charged electrons zip through the Van Allen radiation belts circling Earth. When particles from the sun collide with the planet's magnetic field, which shields Earth from the worst effects, the resulting geomagnetic storms can decrease the number of dangerous electrons.

Where those particles go is something physicists have long puzzled over — and since they could wreak havoc on sensitive telecommunication satellites and pose a risk to astronauts in space, it's an important question, researchers say.

At the heart of the geomagnetic storm mystery are strange dips, known as dropouts, in the number of charged particles in the radiation belts. These lapses can happen multiple times per year, but when the sun is going through an active period — as it is now — the number can increase to several times per month, scientists involved in the new study explained. [Amazing auroras from geomagnetic storms]

Astronomers have previously suggested that the missing particles could have been ejected toward Earth, where they might have been absorbed by the atmosphere. This activity still could explain some of the loss, particularly that which occurs when no geomagnetic storm has been detected, but not all of it.

A team of scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles, observed a geomagnetic storm in January 2011 with a plethora of instruments. They noticed that as intense solar activity pushes against the outer edge of Earth's magnetic field on the daylight side, the lines can cross, allowing the damaging electrons to escape into space.

"Those particles are entirely lost," lead scientist Drew Turner told SPACE.com. The research is detailed in the Jan. 29 edition of the journal Nature Physics.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although material ejected from the sun can deplete the Earth's outer radiation belt, it can also resupply the belt with more charged particles in only a few days, Turner said.

Previous studies have found that the volume of electrons can spike after a solar event. When the belts are first almost depleted, Turner's observations imply a larger influx than previously accounted for.

The team used 11 different satellites, including NASA's five Themis spacecraft and two weather satellites operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the European Organization for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites, to study a small geomagnetic storm. The abundance of spacecraft allowed them to capture a complete picture of the interactions between Earth's magnetic field and the particles streaming from the sun.

"It's impossible to get the sense of the entire process with one pinpoint of information," Turner said.

He called the lineup of the various crafts "lucky."

The upcoming launch of NASA's Radiation Belt Storm Probes Mission (RBSP), scheduled for August 2012, may help to remove some elements of chance from further studies.

"RBSP will provide two more points of view with perfect instruments for radiation belt studies," he said.

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.