Autumn Snow Predicts Winter Weather

A new weather-forecasting model based on autumn snowfall in Siberia could help meteorologists predict winter temperatures and snowfall in the United States and Europe.

The model results, reported this week in the Journal of Climate, could help make climate prediction more accurate and reliable for fields such as agriculture, water management and general weather risks. At least $3 trillion of the U.S. economy is sensitive to weather conditions, estimates the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Scientists led by Judah Cohen of Atmospheric and Environmental Research, Inc. (AER Inc.) verified the sCast (short for "seasonal forecast") model with seven real-time winter forecasts and 33 simulations of winters going back to 1972.

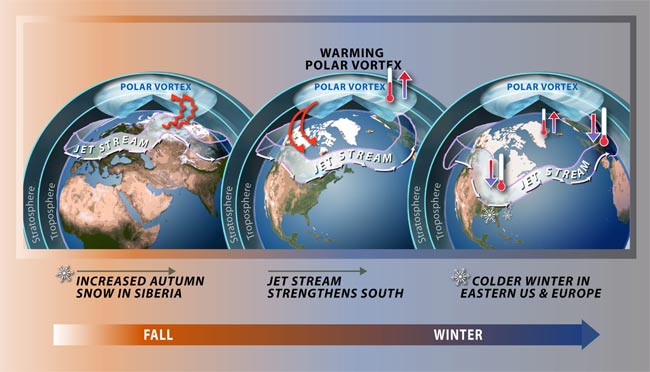

They used weather information from October, a month when snow begins to pile up across Siberia and when the Siberian high develops. This area of high pressure is the dominant weather pattern in the region. The cold air above Siberia enhances atmospheric disturbances, which propagate into the upper level of the atmosphere, called the stratosphere.

"This eventually descends from the stratosphere to Earth's surface over a week or two in January, making for a warmer winter in Northern Hemisphere high latitudes," Cohen said. "However, in mid-latitudes it turns colder, so winters in the northeastern U.S. and eastern Europe are likely to be colder and snowier than normal."

In general, greater-than-average snowfall causes weather patterns in the Arctic to shift southward into mid-latitudes during the winter, while below-average snowfall in Siberia sends the weather patterns poleward.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.