Defective Birth Control Could Spur Big Lawsuits for Pfizer

It's possible that women who become pregnant after taking the defective birth control pills Pfizer recalled today (Feb. 1) could sue the drug company for unwanted pregnancies, experts say. And they could ask for a lot of money.

Courts have typically thought about so-called wrongful pregnancy cases as similar to medical malpractice, said I. Glenn Cohen, assistant professor and co-director of the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School. Similar cases have allowed people to sue for things like unwanted pregnancies after botched vasectomies. In the past, there has even been a case in which a woman successfully sued a pharmacist for a pregnancy that resulted from errors in filling the woman's birth control prescriptions, Cohen said.

The best chance for a case, however, would be for affected women with unwanted pregnancies to band together and bring a class-action lawsuit against Pfizer, said Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania. Such a case could ask for considerably more money than an individual case, and would be more attractive to lawyers, Caplan said.

"I'm sure some enterprising lawyer is already thinking of bringing a class-action lawsuit…against the company," Cohen said.

Another appealing aspect of a class-action lawsuit is that, by pooling people together, a case avoids singling out any individual child who, if it weren't for a defective birth control pill, might not otherwise exist, Caplan said. "Judges and juries don’t tend to want to say 'You'd be better off if you didn’t exist,'" Caplan said.

Just how much money a class-action lawsuit could seek depends on where the suit is filed, Cohen said. Thirty-two states recognize "wrongful pregnancy cases," in which a healthy baby is born from an unwanted pregnancy. Of these states, most allow women to sue for damages related to the cost of the pregnancy itself, and in some states, the cost of emotional distresses from an unwanted pregnancy, and the cost of taking time off from work, Cohen said.

A limited number of states allow women to ask for economic expenses related to raising the child until he or she is 18 years old, which could be hundreds of thousands of dollars in each case.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If many women took part in a class-action suit that sought the price of raising each of the children until the age of 18, "that's a lot of money," Cohen said.

However, before a class-action case can be brought against Pfizer, it would need to be certified by a court, which has become more difficult in recent years, Cohen said.

Moreover, if there are significant differences between the women's cases, it could be even harder for the suit to be certified, Cohen said. For example, if some of the women had healthy babies and some had unhealthy babies, they would file different types of lawsuits, Cohen said. An unhealthy baby would mean a woman would need to file a "wrongful birth" lawsuit.

Other factors could complicate the case. For instance, the cause of the pregnancy could be called into question — Pfizer could allege that a woman had misused the product, and the pregnancy did not result from a faulty product, Cohen said.

Women may also be reluctant to come forward to file a case against Pfizer. Some women may not want others to know they are using birth control, Caplan said. Others may not want to argue in court that they would be better off without their child, he said.

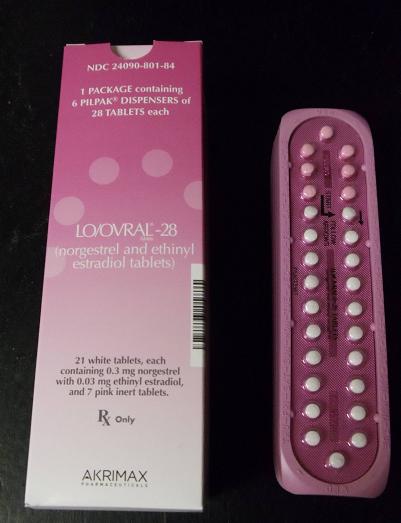

Pfizer has said that the pills in the recalled birth control packages do not pose health risks to the women that take them, but that they may not prevent pregnancy. Women taking the recalled products should being taking non-hormonal birth control immediately, the company said.

Pass it on: Women who become pregnant while taking defective birth control bills may be able to sue the pill's manufacturer.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner. Find us on Facebook.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.