Oldest Copy of 'Mona Lisa' Painted Alongside Original

A copy of Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" was painted by a pupil or follower of the artist at about the same time as the original was created, and is now considered the oldest known copy of the enigmatic piece of work, scientists announced this week.

The painting was previously held in the Spanish royal collections, before it was sent to Madrid in 1819 when the Museo del Prado there was founded. Researchers studying the artwork think it is the painting referred to in 1666 in an inventory of the palace Alcázar in Seville as a female portrait associated with da Vinci. They suspect the copy may have reached Spain in the early part of the 17th century, according to Miguel Falomir Faus, the Prado's curator of Italian Painting up to 1700.

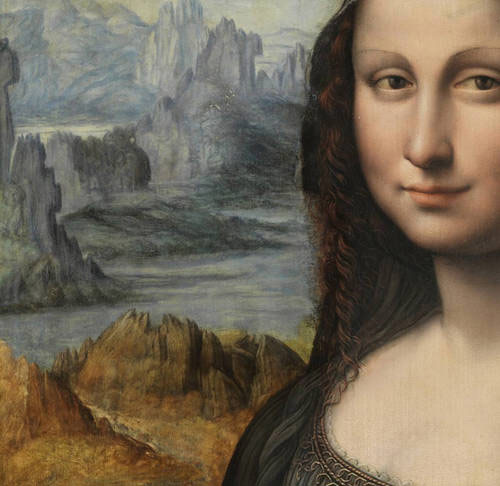

The painting originally received little notice because its sitter is posed in front of a plain black background, not a landscape as in da Vinci's "Mona Lisa." But as conservators were restoring the painting for its inclusion in a da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre in Paris scheduled to open March 29, they found that the black varnish obscured a copy of da Vinci's dreamy countryside. This Mona Lisa copy sheds light on details of the mysterious woman posing in the painting, including the cloth covering her breast, the semi-transparent veil around her shoulders and the shape of the chair. The copy also shows more clearly the landscape in the background.

Previous research has suggested da Vinci did indeed give Mona Lisa eyebrows, though they have since disappeared. That same study, in which an engineer scanned the original painting with various wavelengths of light, also suggested the great artist first painted fingers on the sitter's left hand in a slightly different position.

Scientists have also long wondered the identity of the sitter. Last year, archaeologists reported they had unearthed the skeleton that possibly belonged to Lisa Gherardini Del Giocondo, the women believed to be the model for da Vinci's famous painting, in a Florence convent. Based on an early look at the cranium and pelvis, the skeleton appears to be female, researchers said.

Restoration of the rediscovered copy is expected to be complete in about three weeks. The discovery was announced at the meeting of the Prado's Royal Board of Trustees.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.