Mars 'Super-Drought' May Make Red Planet Too Dry for Alien Life

The surface of Mars may have been parched for too long for any life-forms to exist on the planet today, a new study suggests.

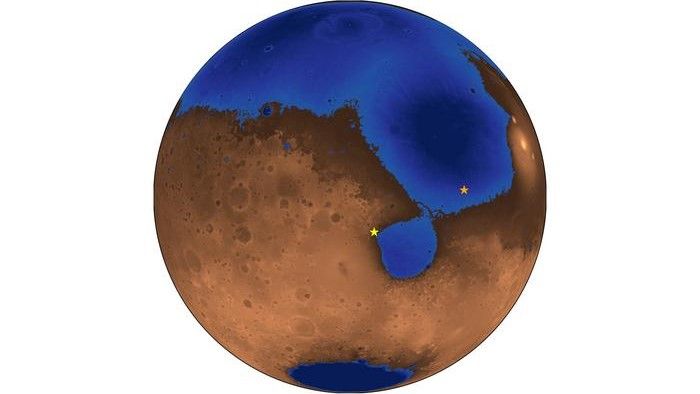

A team of researchers spent three years meticulously examining individual particles of Martian soil collected during NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander mission in 2008. According to their observations, the surface of Mars may have been arid and desolate for more than 600 million years, despite the presence of ice and despite previous studies that indicate the planet may have experienced a warmer and wetter past more than 3 billion years ago.

This could mean that the Martian surface is too hostile to support any life, the researchers said.

"We found that even though there is an abundance of ice, Mars has been experiencing a super-drought that may well have lasted hundreds of millions of years," study leader author Tom Pike, from Imperial College London, said in a statement. "We think the Mars we know today contrasts sharply with its earlier history, which had warmer and wetter periods and which may have been more suited to life."

The results of the study are published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, but the findings will also be discussed at a meeting hosted by the European Space Agency on Feb. 7.

The researchers found that the soil on Mars had been exposed to liquid water for no more than 5,000 years since the planet formed billions of years ago. If this is the case, the water was likely on the surface for too short a time, the scientists said. [Photos: The Search for Water on Mars]

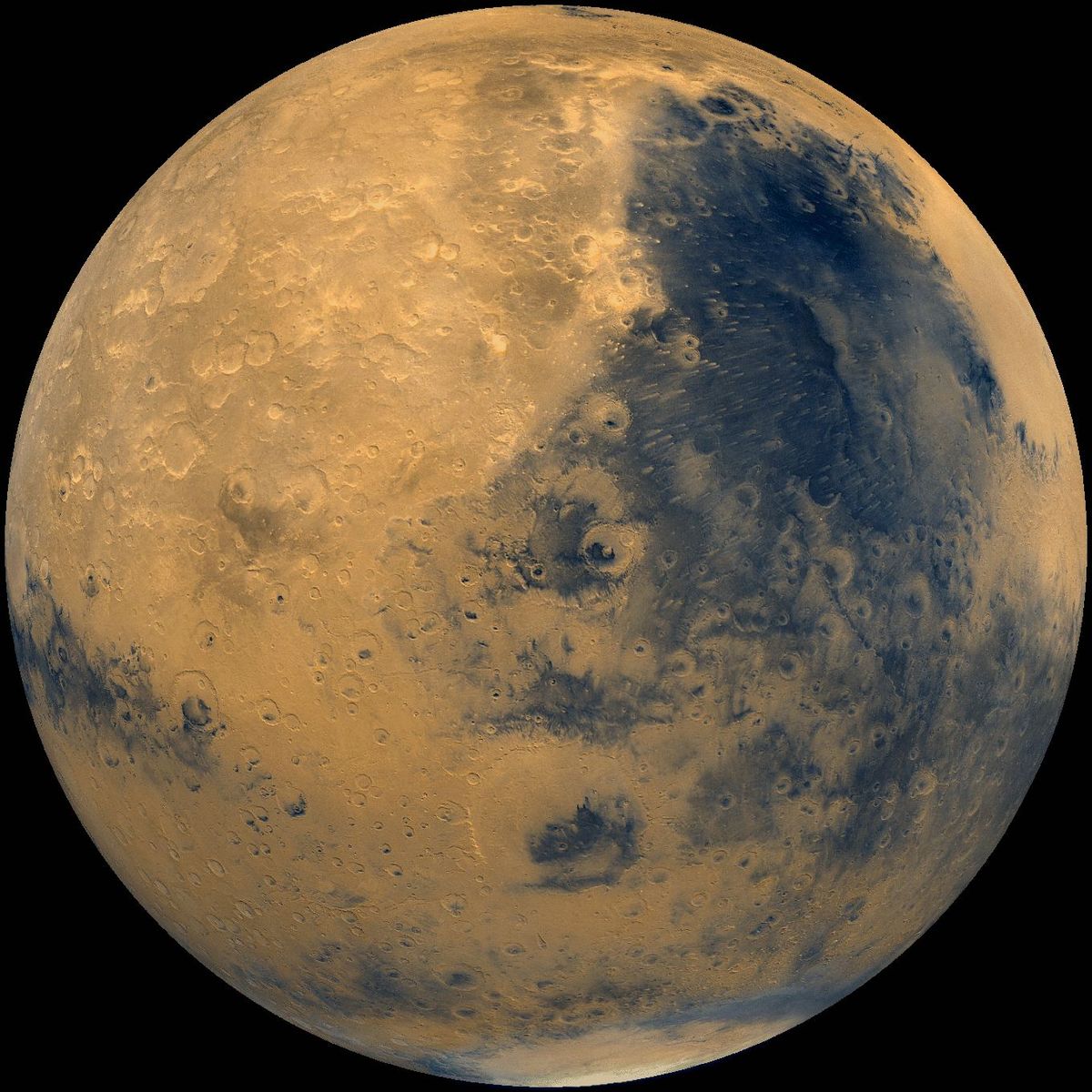

Pike and his colleagues analyzed soil samples dug up by the Phoenix lander's robotic arm. Phoenix touched down in the northern arctic region of Mars to hunt for signs that the planet is or was habitable, and to analyze Martian ice and soil on the surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers used an optical microscope to scrutinize larger sand-size particles, and an atomic-force microscope to make 3D images of the surface to study microscopic particles.

Since the end of the mission in November 2008, the research team has painstakingly cataloged individual particle sizes to glean information about the history of the Martian soil.

The researchers looked for tiny clay particles that are formed when rock is broken down by water. If present, the clay specimens signal an interaction between the soil and liquid water. But the team found no signs of this crucial marker.

Pike and his colleagues calculated that even if the few particles they saw in this size range were clay, they still made up less than 0.1 percent of the soil in the samples they analyzed. For comparison, soil on Earth is made up of 50 percent clay or more, according to the researchers. This indicates that the soil on Mars has had an extremely dry history.

The scientists calculated the slowest rate that clays could form on Earth, and using these models, they determined that the soil on Mars had been exposed to liquid water for only a maximum of 5,000 years.

The researchers also compared soil from Mars, Earth and the moon and found that Martian soil has been largely dry throughout its history. Furthermore, they found that soil on Mars and the moon is being formed under the same arid conditions because they were able to match the distribution of soil particle sizes.

Still, the findings are not necessarily a nail in the coffin or Martian life.

"Future NASA and ESA missions that are planned for Mars will have to dig deeper to search for evidence of life, which may still be taking refuge underground," Pike said.

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.