Just Another Face: Brain Breakdown Hinders Recognition

Some people are better at recognizing a face. Now a study of individuals who have prosopagnosia, a disorder rendering them unable to distinguish another's mug, suggests a possible cause: a breakdown in a brain pathway used to process faces.

This breakdown seems to occur at different places in people with the disorder: About half of patients are able to recognize faces, but the signal gets lost before reaching the brain's higher-order centers. The other half seem to have difficulty analyzing faces to begin with, the researchers found.

"This is something we don't have a handle on. There are probably lots of different types of prosopagnosia. There are connections between these different areas, and there are a lot of places this can break down or fail to develop properly," study researcher Bradley Duchaine, of Dartmouth University, told LiveScience. "In many cases we don't understand why they failed to develop the mechanism necessary for face perception."

Seeing versus recognizing

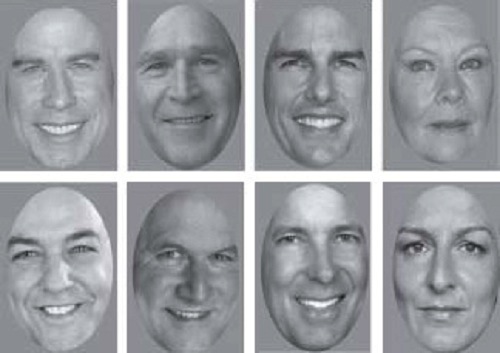

Duchaine brought in 12 people who were born with prosopagnosia and had them look at several photos of faces while their brain activity was monitored with electrodes. The faces included those of well-known celebrities and many people that the patients shouldn't recognize. The researchers compared the brain activities with those of people who recognize faces normally. [Inside the Brain: A Journey Through Time]

A normal brain will show certain responses when it recognizes a face. There will be a strong response after 250 milliseconds in one area of the brain that is responsible for analyzing the visual information from a face and making the connection of whether or not that face is familiar. Then, another response occurs in another area at around 600 ms, which connects that face with higher-level processing including specific information you know about that person.

When the prosopagnosia patients didn't recognize the famous faces, the researchers saw a weak-to-no response at 600 ms, suggesting their brains didn't complete the face-recognition circuit. If they did recognize a face (for example, a president who had been in office for a few years or someone with a unique birthmark), their brains looked just like a normal person's; they showed strong reactions at both 250 ms and 600 ms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An array of abilities

Interestingly, half of the patients showed a normal response at 250 ms and half didn't. The group who responded to the famous faces seems to have normal face-processing and memory abilities, but the signal gets lost when connecting to higher-level processing (the event that takes place at 600 ms) so they aren't able to connect those facial features to information about a known person.

"They are recognizing it at 250 milliseconds, but for some reason that information isn't passed along to those processes that are producing the 600 millisecond response," Duchaine said. "You might imagine there is some kind of disconnection between these [brain] areas, but we don't know what the problem is there."

Recent studies have found that this trait is inherited in families: If your parents are good at remembering a face, you probably will be too. People can also develop prosopagnosia after an accident or stroke in their temporal lobe, which damages the facial recognition centers. Duchaine studied only people who were born with the inability, though.

In contrast to prosopagnosia, some people can remember faces of people they met years ago and only in passing. The "super-recognizers," as they're being called, excel at recalling faces and suggest that there is — as with many things — a broad spectrum of ability in this realm.

Jia-Liu, a researcher at Beijing Normal University in China who wasn't involved in the study, said the study was very interesting. "This study is also important because this marker may be used in diagnosis of prosopagnosia and other cognitive disorders with deficits in face recognition, such as autism," Liu said.

The study was published Jan. 23 in the journal Brain.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.