Sharks' Scales Create Tiny Whirlpools for Speedy Swimming

Razor-sharp scales on their skin seem to make it easier for sharks to race through the water, by generating whirlpools that help pull them along, researchers say.

This research eventually could lead to an artificial shark skin that enhances the swimming of underwater robots, the researchers add.

Harvard University bioroboticist George Lauder and graduate student Johannes Oeffner created a simple robot and placed real shark skin around it to study the skin's properties.

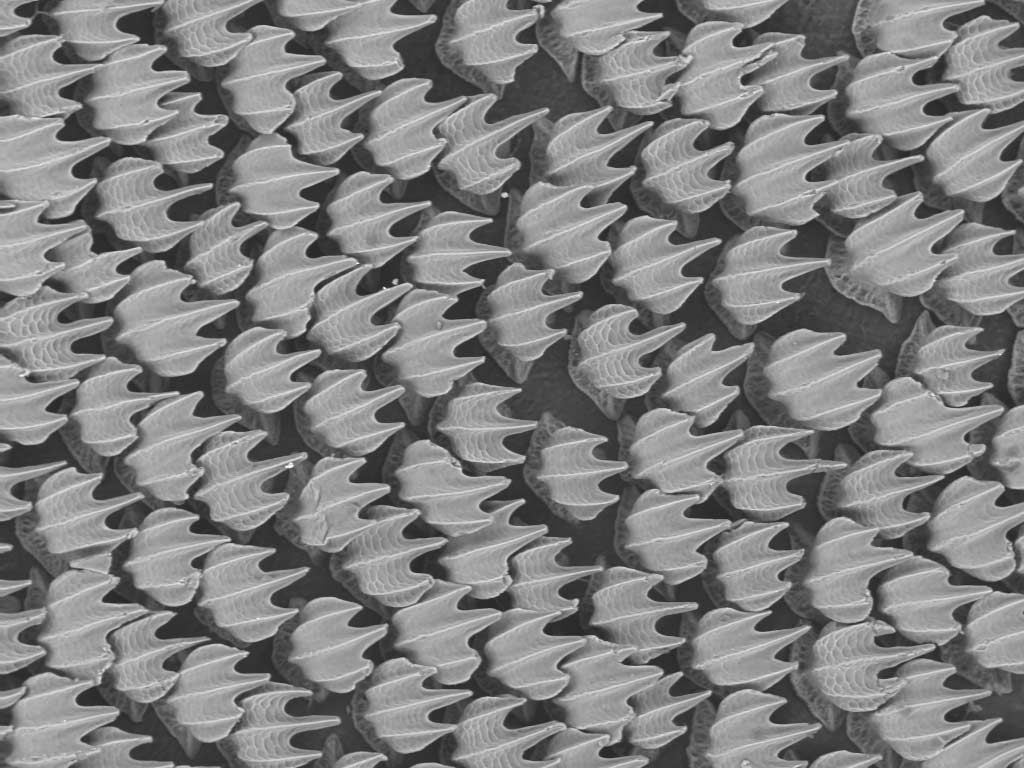

They discovered that the toothlike scales, called denticles, generated vortexes on the front edge of the skin, eddies that essentially would help suck the shark forward. "Leading-edge vortices are well-known in insect and bird flight," Lauder said.

Sharks are renowned for speedily cutting through water. Scientists have been focusing on how the sharks' denticles might boost swimming speed and agility. The sharks' rough skin was thought to behave like the dimples on a golf ball, disturbing the flow of water over the surface to reduce the drag it experiences.

However, existing research into the benefits of shark skin bothered Lauder, since much of it was based on shark skin mimics that were held rigidly in place and laid flat like a sheet of paper. "I have wanted to study the function of shark skin when it moves," he said. [A Gallery of Wild Sharks]

Shark robot

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lauder and Oeffner procured skin from several large mako sharks at a fish market in Boston and glued them onto a rigid piece of aluminum foil. They immersed this foil in a water tank, wiggled it from side to side with a robotic apparatus to make it "swim," and flowed water against it to give it a push. By timing the water flow needed for the flapping device to essentially stay in place, they could determine how fast the robot was effectively swimming.

The researchers then carefully sanded off the denticles to see how the skin performed without them.

"Sanding the denticles off was challenging, and was one of the more difficult aspects," Lauder recalled. "It's hard to sand them off without damaging the underlying skin. Each foil took several hours to do."

Oddly, instead of slowing down, the sanded foil sped up, which at first glance might suggest these scales were impeding the sharks. Harking back to their idea that sharks are flexible and not rigid, the scientists then glued two pieces of shark skin together to create a pliable membrane. They found that flexibility had a dramatic effect: Toothy, flexible surfaces were 12.3 percent faster than sanded ones. [Video of shark experiment]

Next-generation robot skin

The researchers also tested the swimming performance of two shark-skin mimics. One was the Speedo Fastskin FS II fabric, whose bumpy, ridged surfaces are supposed to reduce the drag swimmers experience. The other was a silicone rubber "riblet" — a membrane with sharp-edged ridges on it. "Riblets are being actively studied to put on wind turbine blades to reduce drag, and I believe that one of the America's Cup sailing boats in 1987 used riblets on the hull," Lauder said.

Although the riblets improved the flexible foil's swimming speed by 7.2 percent, the Speedo fabric apparently had no effect at all, perhaps because its bumps were small, rounded and very widely spaced compared with both shark denticles and the sharp-edged riblets. (Lauder did note that figure-hugging Fastskin swimming costumes probably enhance the swimmer's performance in other ways.)

To pin down why denticles might improve shark propulsion, they analyzed how the toothlike scales altered fluid flow around the body. They immersed the flexible shark-skin membrane in a water tank filled with tiny, hollow, silver-coated particles. As they set the machine flapping, they bathed the tank with laser light, which enabled them to see how the membrane set the particles and water swirling.

They learned that shark skin not only reduces drag but enhances thrust.

"The main future direction is manufacturing an artificial shark skin," Lauder said. "The most likely first uses will be to cover underwater robots."

Oeffner and Lauder detailed their findings Feb. 9 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.