Valentine's Bubbly: 9 Romantic Facts About Champagne

Nothing says it's Valentine's Day like the pop of a freshly opened bottle of champagne — well, nothing says it quite so eloquently. The bubbly will do more than tickle your tongue and perhaps your heart, as there's loads of science sealed in as well.

From the physics of the 10 million or so bubbles in each glass and how they burst, to the glass shape's effect on the beverage's taste, here's what science can teach you about champagne.

1. For the best bubbles in your bubbly, try holding the glass at an angle while you fill it, rather than pouring the champagne straight down. A standard bottle contains about six times its volume in dissolved carbon dioxide gas, which is responsible for the liquid's fizz. Even so, for every carbon dioxide molecule that turns into a bubble, four others escape into the air.

2. Science also suggests caution when popping a bottle of bubbly. Corks from champagne or sparkling wine can erupt at speeds up to 60 mph (97 kilometers per hour). At that speed, a cork in the eye can put a serious damper on Valentine's Day romance.

"That is a lot of force to the eye," Mark Melson, assistant professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute, said in 2009. "The damage can range from corneal abrasions to retinal detachment."

3. If you've navigated the cork-popping successfully, you'll soon find yourself in bubbly bliss. In fact, champagne owes its flavor to these bubbles, which carry aromas directly to the nose.

In research published in 2009, scientists found that each champagne bubble carries tens of aromatic compounds — compounds that appear in heavier concentrations in bubbles than in the liquid champagne itself.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I love the idea that such a wonderful and subtle mechanism acts right under our nose during champagne tasting," said Gérard Liger-Belaira of the Laboratory of Enology and Applied Chemistry at Reims University in France. "In a single champagne glass, there is as much food for the mind as pleasure for your senses."

4. Perhaps that's why champagne is traditionally considered a celebratory drink. Sparkling wine has been a part of celebrations in Europe since at least the French Revolution, when the drink became part of secular rituals that emerged to replace earlier religious rituals, according to Kolleen Guy, a professor of history at the University of Texas at San Antonio and author of "When Champagne Became French" (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

"In a secular society, we want to mark both the joy and sanctity of the occasion," Guy told LiveScience's sister site Life's Little Mysteries. "Champagne does this symbolically, but also visually, since it overflows in abundance and joy."

5. While the basic mechanics of the carbon dioxide gas that creates this abundance has long been understood, scientists only recently figured out why bubbles rise in mesmerizing "trains." In 2006, scientists at the University of Reims in France discovered that fibers and gas pockets stuck on the inside of a champagne glass influence the timing of bubble trains, capturing them and allowing them to build up before they release in sparkling chains. So if you (or your date) like your sparkling wine extra-bubbly, towel-dry the glass to leave tiny fibers inside.

6. The word champagne is now reserved for sparkling wines coming from the Champagne region of France, but bubbly was first produced in England in the 1500s, when technology capable of preserving all those bubbles appeared, according to the book "Wine Science, Principles and Applications" (Academic Press, 2008).

7. Today in the United States, the biggest consumers of sparkling wine and champagne are, you guessed it, Californians. In 2009, the state consumed 2,938,370 9-liter cases of bubbly. Illinois came in second, quaffing 1,494,450 cases. [Champagne Facts (Infographic)]

8. Watch out, California: That extra-intoxicated feeling you get after a few glasses of sparkling wine is real. Blood-alcohol levels rise faster in people drinking fizzy champagne compared with people sipping flat stuff, according to research conducted in 2001 at the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom. Forty minutes of drinking bubbly sent people's blood alcohol to 0.7 milligrams per milliliter, compared with 0.58 milligrams per milliliter for people drinking the beverage flat. No one knows why bubbly has this effect, but it may be that the bubbles somehow influence how fast the alcohol gets taken into the digestive system.

9. But champagne just isn't champagne without its bubbles, and science is here to help you make the most of that effervescent experience. A new study, published Feb. 8 in the open-access journal PLoS ONE highlights the effects that glass shape and temperature can have on your champagne-drinking experience.

The researchers, led by Gerard Liger-Belair (GSMA), Guillaume Polidori (GRESPI) and Clara Cilindre (URVVC) of the University of Reims in France, studied the gaseous carbon dioxide and ethanol in the space above the champagne surface after it was poured into either a tall, narrow flute or a wide, shallow coupe. They found a much higher concentration of the gas above the flute than the coupe, which partly accounts for the very different drinking experiences from the two glasses.

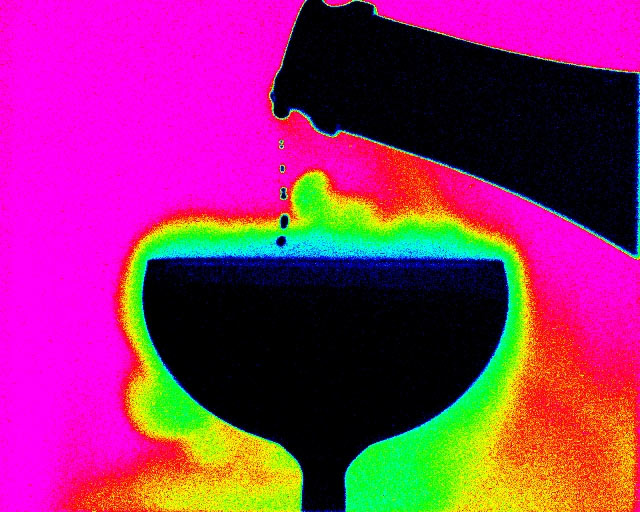

These results were also visualized by infrared thermography, which provided images of the gas escaping from the champagne surface. The authors also determined that, surprisingly, decreasing the champagne temperature did not affect the level of carbon dioxide gas above the flute.

These results "might be a precious resource to depict champagne consumer's sensation according to various tasting conditions, Cilindre said.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.