Candid Camera: Shark Gulps Another Shark Whole

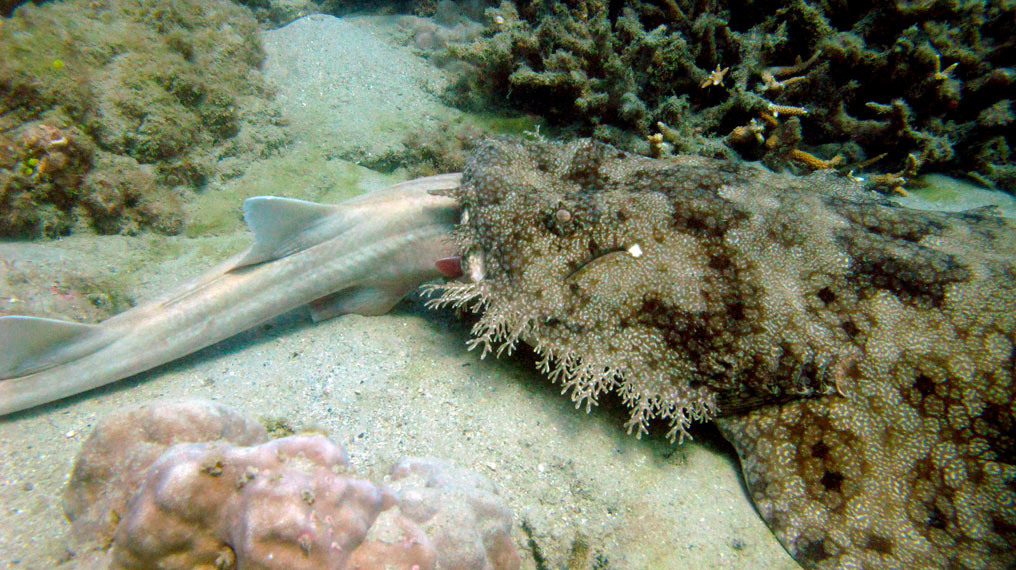

The photo says it all: an alien-looking shark, adorned with mossy hairs and a flat face, with its mouth agape and a slender bamboo shark headfirst inside. Though not unusual for a shark to snack on another shark, it's not typical behavior — and it's certainly not common for humans to catch the action firsthand.

In fact, the researchers who came upon the shark-eat-shark scene on the fringes of Great Keppel Island on the southern Great Barrier Reef didn't realize at first what they were looking at.

"The white bamboo shark appeared first, and as we came closer, we suddenly realized that its head was not hidden under a ledge, as is usual, but in the mouth of the very well-camouflaged wobbegong," Daniela Ceccarelli of Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence (ARC) for Coral Reef Studies, told LiveScience, adding that "witnessing predation events like this is very rare."

Ceccarelli and David Williams, also of ARC, were conducting a fish census there on Aug. 1, 2011, when they spotted the sharks.

The eater in this party was a tasselled wobbegong shark (Eucrossorhinus dasypogon) more than 4 feet long (1.3 meter); the wobbegong's prey was a 3.2-foot-long (1 m) brown-banded bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium punctatum). Like other wobbegong species, this one is an ambush predator, lying in wait on the seabed and then attacking prey at high speed.

"It's not unusual for them to prey on other sharks, especially small sharks such as the bamboo shark, as they forage for invertebrates on the seabed," Ceccarelli said.

They watched the sharks for about 30 minutes, with neither shark moving during that stint. The wobbegong didn't further ingest the bamboo shark, the researchers note in a brief article published online Feb. 4 in the journal Coral Reefs. "We didn't observe the end of the predation event, but as the bamboo shark was most definitely dead, we assume that the wobbegong eventually consumed it," Ceccarelli said. The meal would likely have taken at least several more hours, the researchers point out in their paper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Wobbegongs also have jaws that can dislocate, a large gape and sharp, rearward-pointing teeth, allowing them to grasp relatively large prey before swallowing it whole, the researchers noted.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.