How Malaria Parasite Morphs to Sneak Into Body

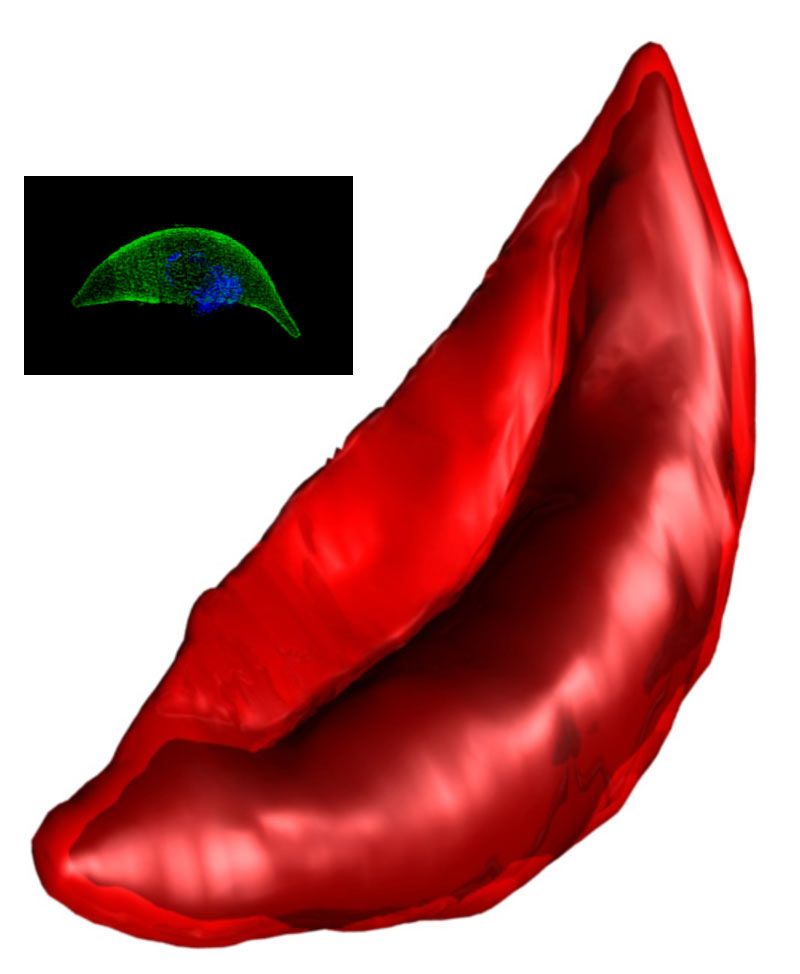

The first time doctors saw the odd banana-shaped malaria parasite was in 1880, and since then, scientists have been puzzled over how the lethal parasite goes about its shape-shifting. New research may have solved the mystery, revealing malaria uses a scaffold of proteins to contort its spherical body into a banana shape before sex.

The finding may explain why the parasite, called Plasmodium falciparum, is so skilled at invading the immune system and may provide targets for vaccines or drug development, the researchers said. The disease is often a particularly lethal one; one child dies from malaria every minute in Africa, according to the researchers. In 2010, there were about 216 million cases of malaria, and an estimated 655,000 malaria-related deaths, mostly among African children, according to the World Health Organization.

"As the malaria parasite can only reproduce in its 'banana form,' if we can target these scaffold proteins in a vaccine or drug, we may be able to stop it reproducing and prevent malaria transmission entirely," study researcher Matthew Dixon of the University of Melbourne in Australia said in a statement.

The researchers used 3D microscopy to get a close look at the parasite, which in its banana shape gets passed from a human host to a mosquito's gut, where it reproduces.

The microscopy revealed that specific proteins assemble into scaffolds, or girders (called microtubules), underneath the parasite's membrane. "This process of laying down more membrane and more support 'girders' continues until the parasite reaches its final length," Dixon said. Once the parasite is fully extended, the scaffolding is disassembled, leaving behind the elongated membrane that holds the parasite in its banana shape. The process from spherical shape to banana shape takes about seven to 10 days, he added.

"This stage of the parasite is then ready to circulate in the bloodstream and to be taken up by feeding mosquitoes and undergo sexual reproduction," Dixon said.

The results, detailed Feb. 14 in the Journal of Cell Science, suggest that when ready for sexual reproduction, the malaria parasites adopt their banana shape so they can fit through tiny, winding slits in the spleen. "Given the small size of the fenestrations [or slits] in the spleen, it is easier to squeeze an elliptical or banana-shaped parasite through the holes than a flat or round object of the same volume," Dixon told LiveScience in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study was led by Dixon and Melbourne doctoral student Megan Dearnley.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.