Space Probe Spots Weird Microwave Haze in Our Galaxy

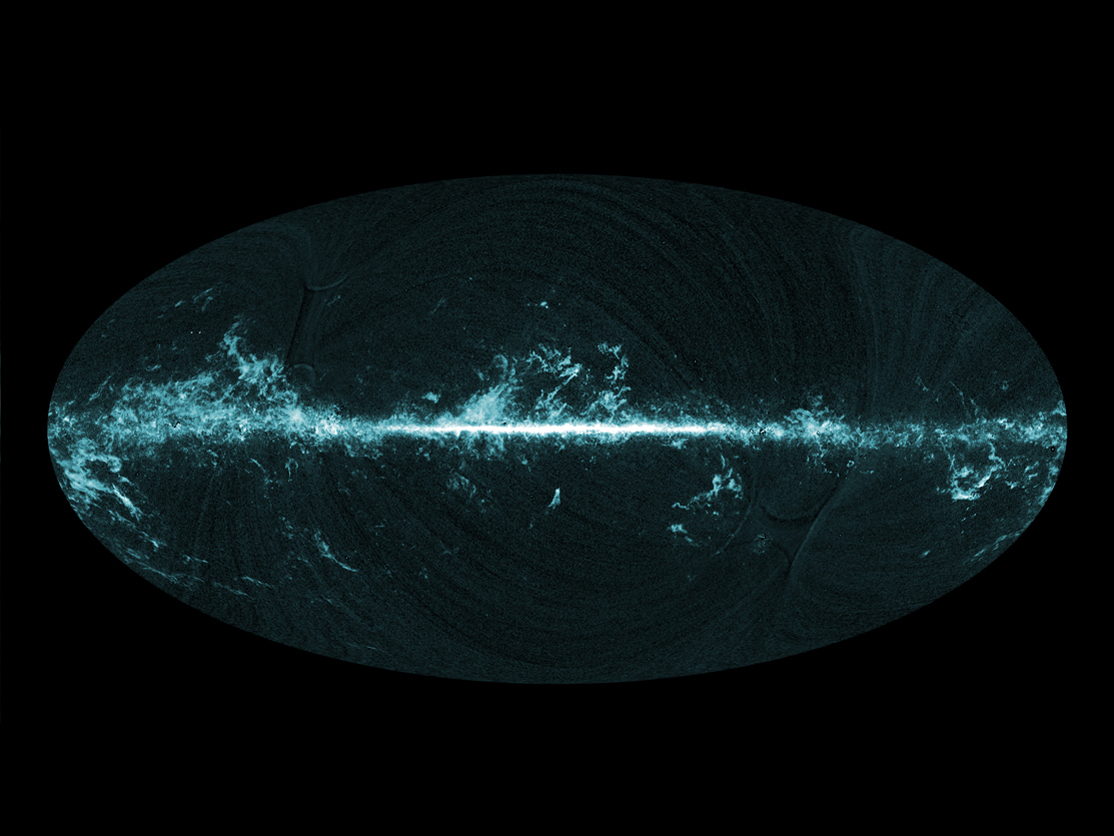

A European spacecraft has snapped new images of our Milky Way galaxy, confirming the puzzling presence of a shroud of microwave fog around the galactic core.

The new images come from the European Space Agency's Planck spacecraft, which showed the odd microwave haze during a survey that also turned up previously unseen patches of cold gas where new stars are forming.

The energy haze was hinted at by a previous NASA mission, but the Planck measurements confirmed its existence, researchers said. The Planck findings should help scientists construct a more-detailed blueprint of the cosmos, they added.

"The images reveal two exciting aspects of the galaxy in which we live," Planck mission scientist Krzysztof Gorski, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Poland's Warsaw University Observatory, said in a statement Monday (Feb. 13). "They show a haze around the center of the galaxy, and cold gas where we never saw it before."

Our hazy galaxy

The microwave light comes from a region surrounding the galactic center, and it looks like a form of energy called synchrotron emission, which is produced when electrons pass through magnetic fields, Davide Pietrobon, another Planck scientist at JPL in Pasadena, Calif., explained in a statement. [Gallery: Planck Spacecraft Sees Big Bang Relics]

"We're puzzled though," Gorski said, "because this haze is brighter at shorter wavelengths than similar light emitted elsewhere in the galaxy."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Several explanations have been proposed, including galactic winds, higher rates of supernova explosions and the annihilation of dark matter particles.

Where stars are born

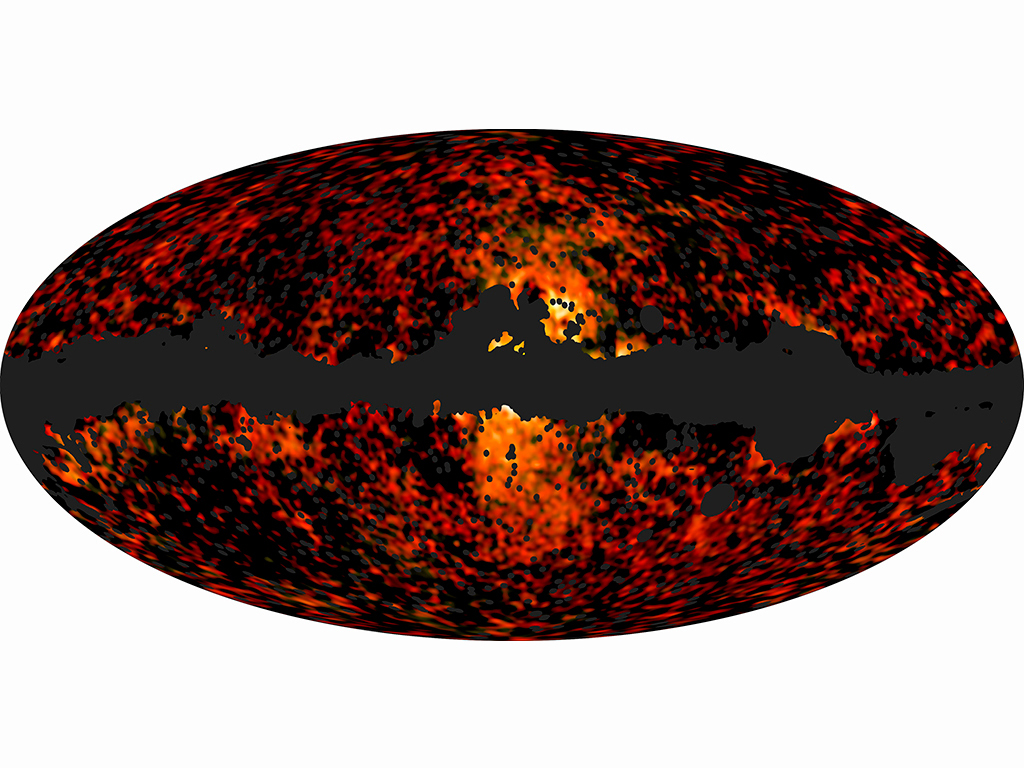

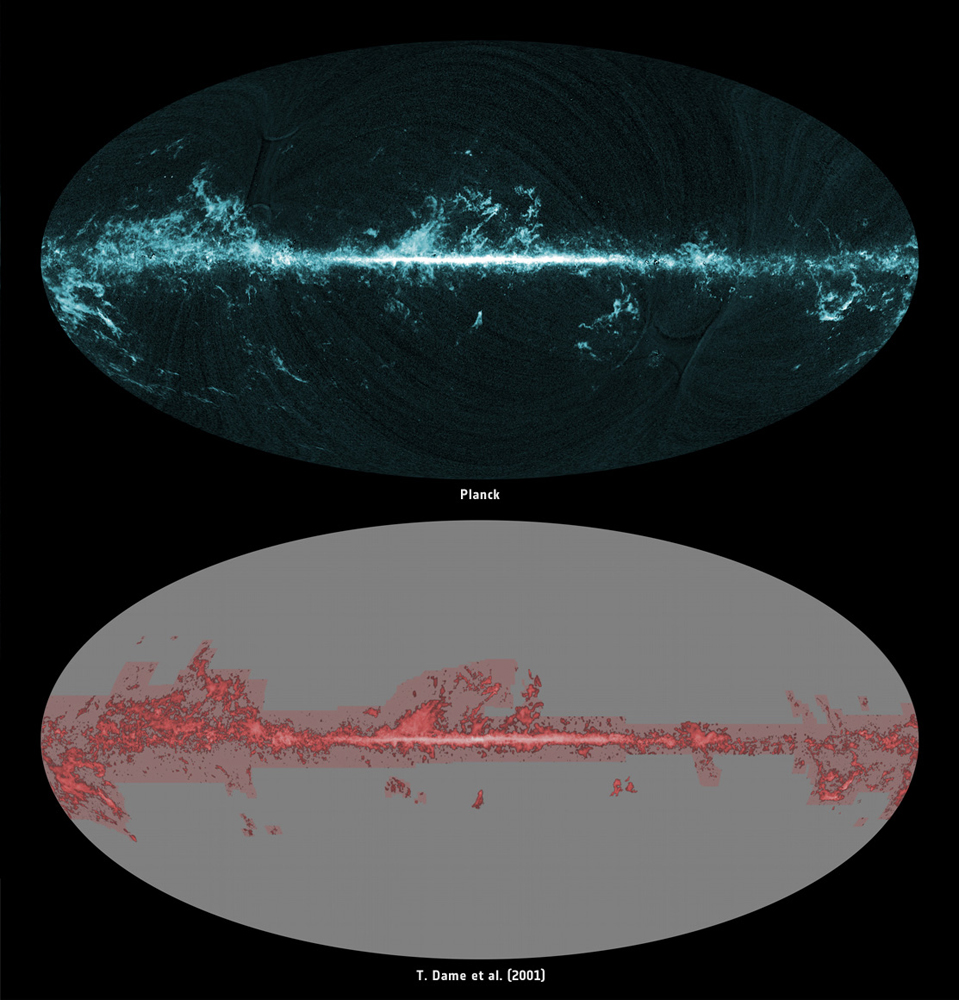

One of the other newly released all-sky images from Planck is the first to map the distribution of carbon monoxide across the entire sky.

Clouds of cold gas in the Milky Way and other galaxies are predominantly made of hydrogen molecules, which make the clouds difficult to see because they do not emit much radiation. Molecules of carbon monoxide are much rarer, but they form under similar conditions and emit more light. By scanning the sky for carbon monoxide, astronomers can then pinpoint the more elusive clouds of hydrogen where stars are born.

Mapping carbon monoxide is a time-consuming process using radio telescopes on the ground, so previous studies focused on portions of the sky where clouds of molecules were known or expected to exist.

But Planck is able to scan the whole sky, which makes traces of the gas detectable in places that have not been probed before, the researchers said.

"The results achieved thus far by Planck on the galactic haze and on the carbon monoxide distribution provide us with a fresh view on some interesting processes taking place in our galaxy,” Jan Tauber, ESA’s project scientist for the Planck mission, said in a statement.

The Planck observatory was launched in 2009 on a mission to take some of the most detailed measurements yet on the cosmic microwave background (CMB), a relic of the Big Bang that is believed to have created the universe. After 13.7 billion years, the CMB lingers in the cosmos as a pocked veil of radiation.

By studying the CMB, scientists are hoping to understand what our universe is made of and the origin of its structure. But the radiation can be reached only after all the foreground emissions, which include the galactic haze and the carbon monoxide seen by Planck, have been identified and removed.

"The lengthy and delicate task of foreground removal provides us with prime data sets that are shedding new light on hot topics in galactic and extragalactic astronomy alike," Tauber said.

The new findings from the Planck mission are being presented this week at an international astronomy conference in Bologna, Italy. The first round of findings on the CMB radiation from the Planck mission are expected to be released in 2013.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.