Fossil Footprints Reveal Oldest Elephant Herd

The world's oldest elephant tracks have now been revealed, 7-million-year-old footprints in the Arabian Desert, researchers say.

These prehistoric footsteps, likely the work of some 13 four-tusked elephant ancestors, are the earliest direct evidence of how the ancestors of modern elephants interacted socially, and the oldest evidence of an elephant herd.

"Basically, this is fossilized behavior," said researcher Faysal Bibi, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Museum for Natural History in Berlin. "This is an absolutely unique site, a really rare opportunity in the fossil record that lets you see animal behavior in a way you couldn't otherwise do with bones or teeth."

The site, known as Mleisa 1, is in the United Arab Emirates. The region then was home to a great diversity of animals, including elephants, hippopotamuses, antelopes, giraffes, pigs, monkeys, rodents, small and large carnivores, ostriches, turtles, crocodiles and fish. These were sustained by a very large river flowing slowly through the area, along which flourished vegetation, including large trees. The animals resembled those from Africa during the same time, though there are also similarities with Asian and European species of that period.

Fossil trackways in the region have been long known to locals, and were taken to be the prints of dinosaurs or giants of ancient myth. It was not until January 2011, when researchers mapped the area from the air for the first time, "that we realized what we had and how we could go about studying it," Bibi said. [The Creatures of Cryptozoology]

"Once we saw it aerially, it became a much different and clearer story," said researcher Brian Kraatz at Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, Calif. "Seeing the whole site in one shot meant we could finally understand what was happening."

The footprints cover an area of 12.3 acres (5 hectares). This is about equal to nine U.S. football fields, seven soccer fields, or the base of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The trackways are visually stunning," said researcher Andrew Hill at the University of Poitiers in France. "It is quite obvious to anyone, without any technical knowledge, that these are the footprints of very large animals, and to learn that they are over 6 million years old presents a visitor with the sensation of walking back in time."

The researchers noted that while these prehistoric titans were proboscideans like modern elephants, they likely looked quite different. Of the three kinds of fossil proboscidean species in the area at that time, the one that most likely made the trackways was Stegotetrabelodon syrticus, the earliest known member of the elephant family, "which carried tusks in both its upper and lower jaws," Bibi told LiveScience.

The trackways stretch up to about 850 feet (260 meters) long, making them "the most extensive ever recorded for mammals, and to view them is to be transported 7 million years back in time when herds of four-tusked primitive elephants and other related behemoths roamed a wetter and more vegetated Arabian Peninsula," said paleontologist William Sanders at the University of Michigan, who did not take part in the study. [Photos of Elephant Trackways]

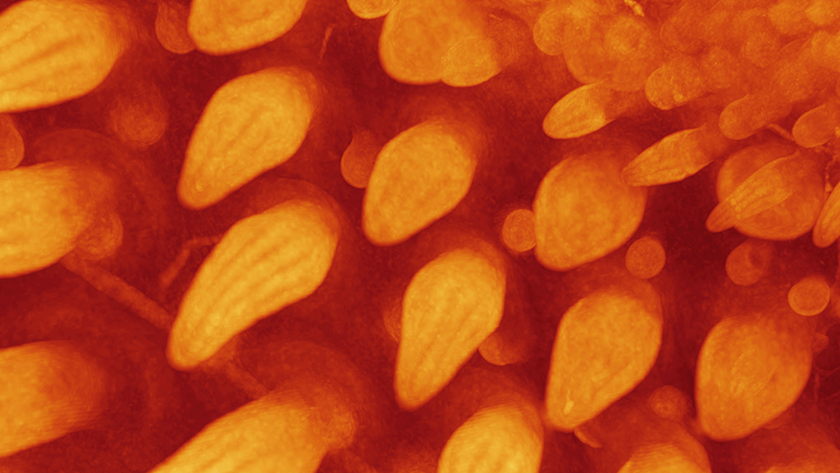

Actually mapping these footsteps proved challenging, since the individual tracks are each only about 15 inches (40 centimeters) wide, too small to show up in satellite imagery. To do so, researchers mounted a pocket digital camera onto a kite, stitching the hundreds of pictures it took into a single large mosaic image that gave a broad overview of the site.

Analysis of the footsteps suggests they belonged to a herd of at least 13 elephants of different sizes and ages that walked through mud, leaving behind tracks that hardened, were buried, and then re-exposed by erosion.

The researchers also discovered tracks from a solitary male traveling in a different direction from the herd. These suggest the extinct giants divided into solitary and social groups, just as elephants do today. Also, these ancient pachyderms might have structured themselves along lines of sex just as their modern relatives do, with the males leaving the herd to live alone.

"Like the human handprints in Paleolithic caves, animal trackways crystallize in time [the] identity and behavior of the organisms that made them, and yield rare insights about these organisms, which fossil bones alone cannot provide," Sanders said.

The scientists detail their findings online tomorrow (Feb. 22) in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.