One Year Later: Lessons Learned from Deadly Japan Earthquake

VANCOUVER, British Columbia — In 2011, Japan was one of the most prepared countries in the world for a massive earthquake. Yet when a mega-quake hit Japan last March, sparking a huge tsunami, it was shockingly devastating.

Now, almost a year after the Japan earthquake, scientists say the hard lessons learned will go a long way toward being better prepared next time.

"It was very large and largely unanticipated by many seismologists," James Mori of Kyoto University's Disaster Prevention Research Institute said here Sunday (Feb. 19) at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. "It was actually very disheartening for all the people doing earthquake research and hazard mitigation in Japan."

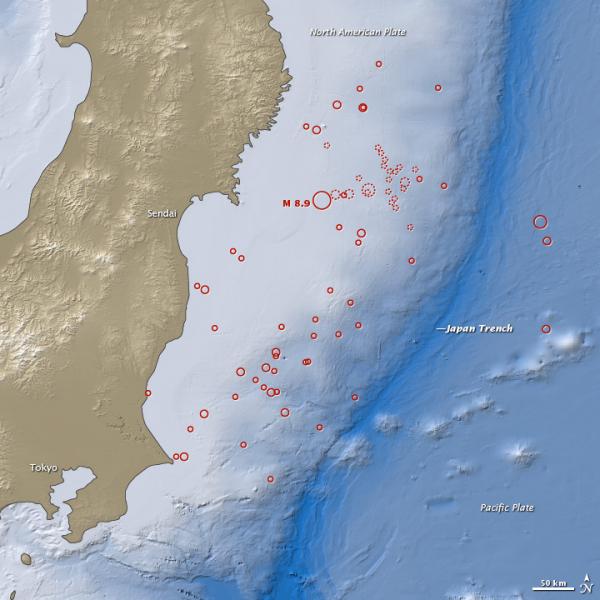

The quake, a whopping 9.0 on the magnitude scale used to rate the severity of earthquakes, struck off the east coast of Japan's Tohoku region on March 11. The temblor, the strongest ever to hit Japan and among the five most powerful earthquakes ever recorded, caused a massive tsunami wave that reached heights up to 133 feet (40.5 meters).

More than 22,000 people were reported dead or missing.

"The fact that tens of thousands of people were killed was really a shock," Mori said. "I think people thought that such kinds of events wouldn't happen in Japan with all the work put into earthquake research and hazard mitigation."

Lessons learned

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Part of the reason scientists weren't expecting such a strong quake in Japan was the fact that a quake that powerful had never before been recorded, and seismic predictions based on the known record of earthquakes in Japan did not forecast such an event.

"The lesson is that 400 or 500 years of historical records is not enough," Mori said.

In the wake of the Tohoku quake, researchers hope to make significant improvements to earthquake models and forecasting, both for Japan, and for the entire planet. They have a wealth of data to work from, as no other large earthquake in history has been recorded by as many instruments with as much precision, said John Anderson, a seismologist atthe University of Nevada.

"At last we have a very well-recorded mega earthquake, and the data is extraordinary," Anderson said.

For example, the data reveal that the ground motions were actually less violent than might have been predicted for such a huge earthquake. Between that fact, and the high building standards in Japan that ensured many structures were designed to withstand strong quakes, the property damage and loss of life from the earthquake alone were not as significant as they could have been.

"The shaking itself was not responsible for a large fraction of deaths — it was mostly the tsunami," Anderson said.

Disaster response

In addition to shedding light on the science of earthquakes, the experience of Japan is shaping ideas of how best to respond to disasters.

While Japan has in place a high-tech warning system to alert the public when an earthquake is imminent, it didn't work as well as it might have last March.

The warning was issued just eight seconds after the first wave of the earthquake was detected, Mori said. It sent a message to 124 television stations and 52 million phones. It automatically caused bullet trains to stop and elevators to halt.

However, calculations of the earthquake's likely strength based on the initial wave turned out to be wrong because the earthquake increased in power over time. Consequently, the system underestimated the severity and extent of the temblor, and the warning was not sent to places like Tokyo, which initially seemed too far to be affected, but actually was.

"That's just one of the inherent problems of the system and something that has to be dealt with," Mori said.

Furthermore, the tsunami warning, which followed the earthquake warning, did not reach many coastal residents who had already evacuated, or whose televisions and radios had stopped working due to power outages sparked by the earthquake.

Despite the fact that the tsunami hit 30 to 60 minutes later than the earthquake, many people had no warning of this more dire threat. [History's Biggest Tsunamis]

In the future, better alert systems are needed to send out updated information to the public before and during an emergency, the experts said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.