Tiny 'Soccer Ball' Space Molecules Could Equal 10,000 Mount Everests

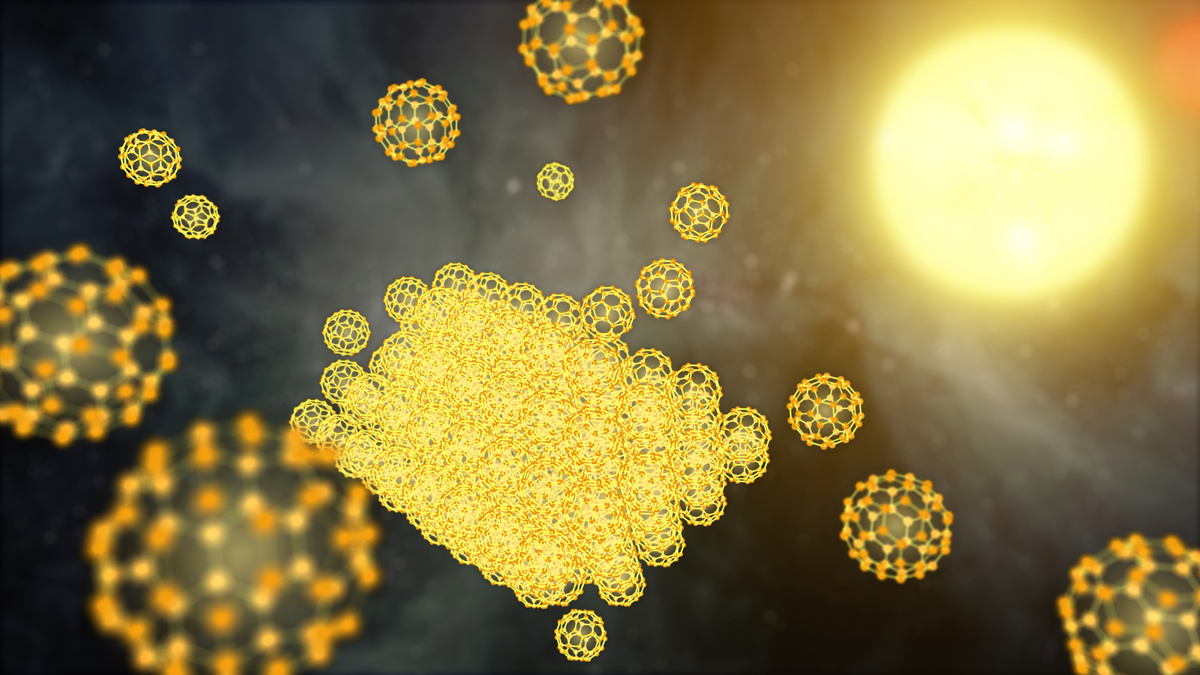

For the first time, astronomers have discovered the solid form of tiny carbon spheres in deep space inside a vast cloud of particles locked in orbit around two distant stars.

The carbon spheres, known as buckyballs, are formed from 60 carbon atoms linked together to form a hollow sphere, "like a soccer ball," NASA announced in a statement today (Feb. 22). Astronomers spotted vast quantities of the tiny space balls, enough to create 10,000 Mount Everests, circling a pair of stars 6,500 light-years from Earth.

"These buckyballs are stacked together to form a solid, like oranges in a crate," said the study's lead author Nye Evans of Keele University in England in a statement. "The particles we detected are miniscule, far smaller than the width of a hair, but each one would contain stacks of millions of buckyballs."

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, a space-based infrared observatory, spotted the buckyballs around the double-star system XX Ophiuchi. The light emitted by the carbon spheres is different than that seen in the gaseous form of buckyballs previously seen in space, allowing scientists to conclude that Spitzer had detected the material in its solid form, researchers said.

Buckyballs are also known as buckminsterfullerene. They take their name from the geometric arrangement of their carbon atoms, which resembles the geodesic dome designs of the late architect Buckminster Fuller.

On Earth, buckyballs can be used in superconductors, medicines, water purifiers and armor, NASA officials explained. They can form naturally as a gas from burning candles and appear in solid form in rock minerals.

Buckyballs can also be created artificially and appear as a solid dark "goo" in test tubes, NASA officials said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But astronomers had never seen the solid form of buckyballs in space until now.

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope detected the first signs of gaseous buckyballs in space in 2010, and ultimately found enough of the material to fill 15 of Earth's moons inside the Small Magellanic Cloud, a small neighboring galaxy to our own Milky Way.

However, knowing that gaseous material can coalesce into solid buckyballs such as those spotted by Spitzer takes the cake, researchers said.

"This exciting result suggests that buckyballs are even more widespread in space than the earlier Spitzer results showed," said Mike Werner, NASA's Spitzer telescope project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "They may be an important form of carbon, an essential building block for life, throughout the cosmos."

The research is detailed in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

This story has been corrected to reflect that buckyballs are made up of 60 carbon atoms, not molecules.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.