Life Surprisingly Thrives Near Deepest Spot on Earth

Life finds a way, even in the total darkness near the deepest known part of the ocean, according to new research.

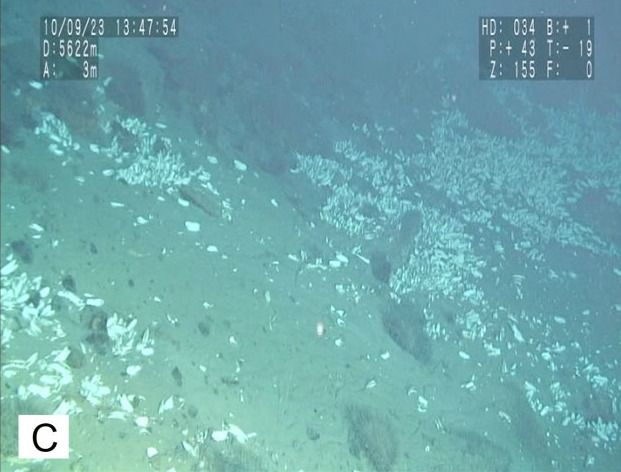

Scientists have discovered fields of bone-white clams clustering near hydrothermal vents in the western Pacific Ocean that lie as deep as 19,230 feet (5,860 meters) below the surface, near the Mariana Trench, the deepest point on Earth's surface.

The discovery, made during a September 2010 expedition, was utterly unexpected, according to a study on the find published in a recent issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Deepest of the deep

Scientists aboard a manned submersible were conducting research dives to study the geology of a region of the Mariana Trench, the deepest trench on Earth, which lies several hundred miles south of the island of Guam. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

The researchers happened upon the hydrothermal vents just 50 miles (80 kilometers) northeast of the Challenger Deep— the deepest spot on the planet, where the seafloor plunges to 35,700 feet (10,880 meters).

In addition to clams, the team saw or collected various deep-dwelling sea anemones, snails, at least one type of comb jelly known for producing shimmering bioluminescence, and at least one crab that has long, reaching front pincers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team retrieved 30 clams from the site, along with 170 pounds (77 kilograms) of rocks.

The vents may be the deepest ever discovered. The team named them the Shinkai

Seep Field, for the vehicle that allowed the find, the Shinkai 6500, a Japanese manned submersible with one of the deepest ranges of any vehicle on the planet.

Different kind of vent

However, unlike the deepest known active volcanic vents on Earth — the Piccard/Beebe vents, which lie 16,400 feet (5,000 meters) below the Caribbean — the newfound Pacific vents are not superheated by volcanic forces, but are a cooler type of hydrothermal vent. They spew heated, chemically-rich water, but is not fueled by volcanic activity, but is instead driven by the collision of two oceanic plates.

"These kinds of low-temperature fluid vents are very difficult to find and may be very widespread on the ocean floor," said Robert Stern, a professor of geosciences at University of Texas Dallas, and one of the paper's authors, in a statement.

"And they can sustain high-biomass communities," he added. "This has implications for the chemical composition of the oceans and the distribution of deep-sea life."

The discovery comes on the heels of a string of revelations about life at hydrothermal vents around the globe. Scientists have uncovered yeti crabs living on vents near Antarctica, and expeditions to the Piccard/Beebe sites in the Caribbean uncovered eyeless shrimp.

The Shinkai vents were discovered by a joint team of geoscientists from the United States and Japan. Stern said he and his colleagues are proposing to return to the region within the next year or two.