Andromeda Galaxy's Exotic X-Ray Signal Actually a Bright Black Hole

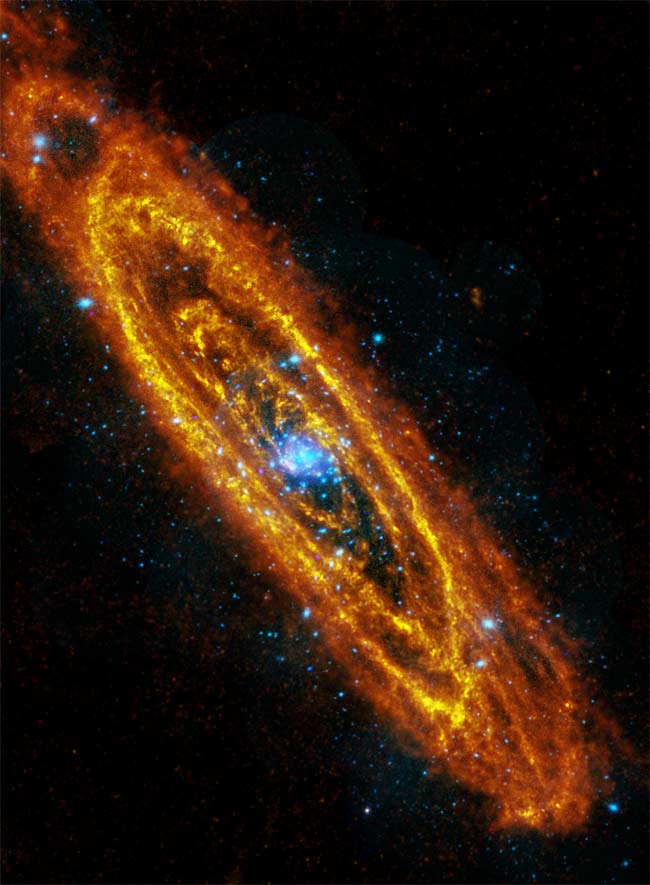

An intensely bright X-ray beacon shining in the Andromeda galaxy is actually a signpost for a hungry black hole that is gobbling up matter at a furious pace, new studies reveal.

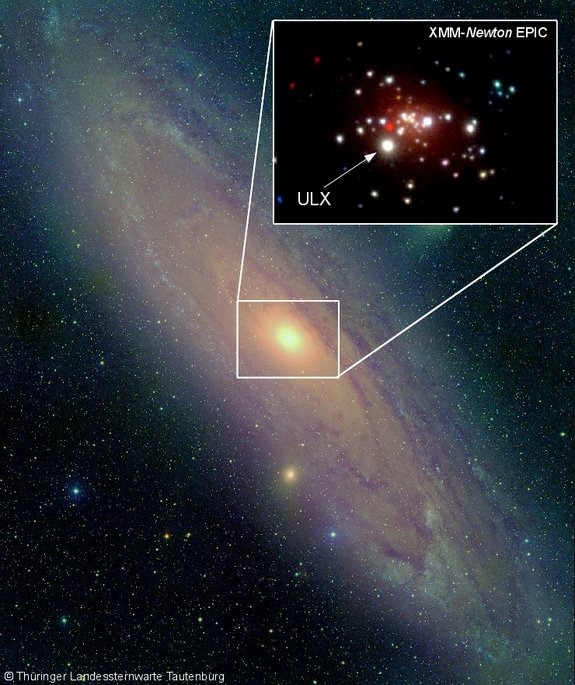

NASA's Chandra X-ray observatory first discovered the so-called ultraluminous X-ray source (ULX) in late 2009 in the Andromeda galaxy, which is located about 2.5 million light-years away from our own Milky Way galaxy.

Now, an international team of scientists say that this extremely bright object is the result of a stellar black hole gorging on large amounts of matter. These black holes rapidly guzzle their surrounding gas and dust to form an accretion disk that heats up and unleashes X-ray jets.

This ULX is the first one spotted in the spiral Andromeda galaxy, and is also the closest ULX ever seen, the researchers said.

Stellar black holes are formed by the collapse of massive stars and typically contain up to 10 or 20 times the mass of the sun. According to the new studies, the black hole causing the ULX object in Andromeda is at least 13 times more massive than our sun and formed after a massive star ended its life in a spectacular supernova explosion.

"ULX sources are still pretty exotic," study leader Matt Middleton, a research associate in the Department of Physics at Durham University in the U.K., said in a statement. "But our work shows that at least some are linked to the normal black holes left behind after the death of massive stars, objects that are found throughout the universe, and the way that they drag in surrounding material. The ULX in Andromeda flared up because of the black hole's voracious appetite for new material." [Photos: Black Holes of the Universe]

The research is detailed in studies published in two separate journals: Astronomy and Astrophysics and the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Their results could help astronomers better understand Ultraluminous X-ray sources and what causes them, the researchers said. Many of these objects are too distant to study, but the relatively close Andromeda galaxy gave scientists an opportunity to analyze the phenomenon in detail, without being obscured by large amounts of interstellar gas and dust.

Previously, some scientists predicted that ULX sources were caused by relatively small black holes that are only a few times as massive as the sun. Other scientists pointed to medium-size black holes that can be up to 1,000 times bigger than the sun and are formed by the merger of many stellar black holes.

The findings of the new studies show that the ULX spotted in Andromeda is likely caused by a normal stellar black hole that was formed by the collapse of a massive star.

The researchers monitored the ULX using data from Chandra, the XMM-Newton X-ray observatory, the Swift gamma-ray observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. Over the course of a few months, the scientists saw a sharp decline in the X-ray luminosity, which had not been seen in any ULX before.

This type of behavior is commonly seen with X-ray binaries — where a normal star is in a close orbit around a black hole — that are found in our Milky Way galaxy. By measuring the energy emissions from the ULX, the scientists were able to rule out the possibility that an intermediate-mass black hole was causing the uptick in X-rays that was originally detected.

"We were very lucky that we caught the ULX early enough to see most of its light curve, which showed a very similar behavior to other X-ray sources from our own galaxy," Wolfgang Pietsch, of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, said in a statement. "This means that the ULX in Andromeda likely contains a normal, stellar black hole swallowing material at very high rates."

The researchers plan to keep a close eye on the Andromeda galaxy, in hopes that one of the orbiting X-ray observatories will pick up another ULX in our cosmic neighbor. This would provide them with a valuable opportunity to test their theory.

"We would like to follow up this work by watching another outburst from the Andromeda ULX," Middleton said. "The problem is that these are likely to happen only every few decades so we could be in for a long wait before this source erupts again. If we do manage to spot another ULX outburst in Andromeda it will be a big help in understanding the extreme behavior of black holes and the way they pull in matter — something of great importance in shaping the wider universe."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.