Spinning Star's Vanishing Act Reveals Cosmic Mystery

Pulsars are fast-spinning stars that emit regular beams of light known for their clocklike regularity. So, when one strangely turned off for a year and a half, astronomers were surprised to find that this abnormality could help them solve the longstanding mystery of what makes these flashing stars tick.

Despite more than forty years of study, astronomers still can't nail down what causes these rapidly rotating stars to pulse. But when one, called PSR J1841, turned off for 580 days, it gave astronomers a glimpse of how pulsars behave when they can't be seen.

In December 2008, Fernando Camilo, of Columbia University in New York, was using the Parkes telescope in Australia to search for a known object when he found a steadily flashing star in his field of view. He quickly identified it as a pulsar that was spinning once every 0.9 seconds — a fairly standard rotation.

"I wasn't too excited," Camilo admitted to SPACE.com.

His team continued to study the pulsar over the course of a year to help determine the characteristics of the new discovery, which orbits 22.8 light-years from the sun in the Scutum-Centaurus spiral arm of our Milky Way galaxy. Just as he was about to conclude his follow-up observations, the star disappeared. [Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

"At first, I thought there was something wrong with my equipment," Camilo said.

But after several tests, it was obvious that the pulsar had vanished.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I realized, it's really off now."

A vanishing star

Out of approximately 2,000 known pulsars, less than 100 stop pulsing completely. For most of them, the cessation is on the order of only a few minutes.

"Pulsars generally are steady emitters of radio pulses," Camilo said.

But "for a few rotations, some turn off."

Only one other pulsar has been found to vanish for more than a few minutes at a time — PSR B1931+24 turns on for a week at a time and then shuts off for a month.

Camilo concluded that he and his team had found another strange specimen.

For a year and half, he continued to observe the sky, waiting for the pulsar to return. He was hesitant to publish his findings to announce a unique object that was no longer visible for other astronomers to perform follow-up observations.

Then, in August 2011, the pulsar reappeared.

Not completely in the dark

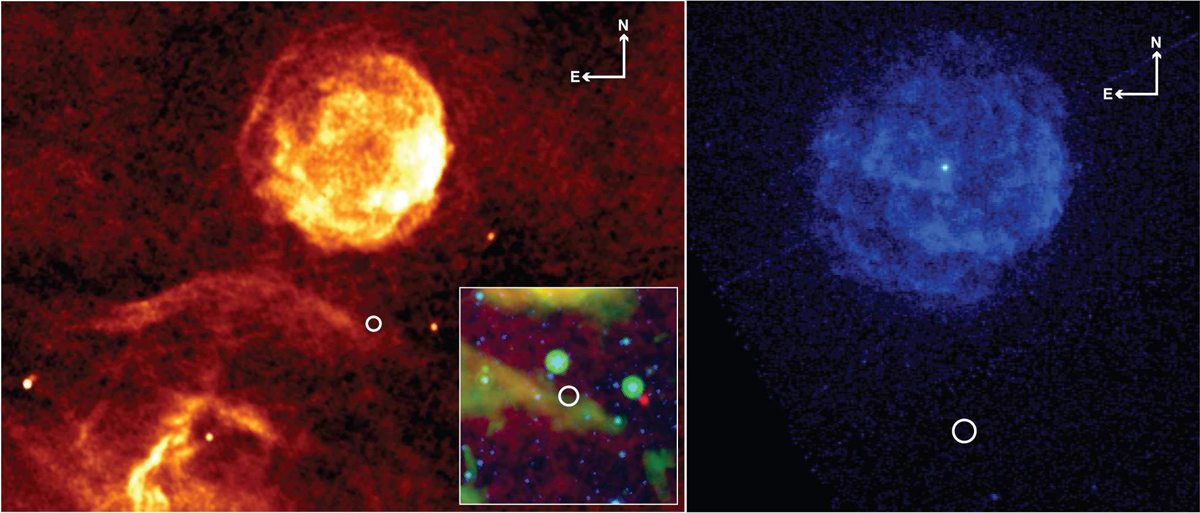

Born in explosive supernova blasts, pulsars are small, super-dense stars that rotate rapidly and emit a ray of high-energy light that sweeps around like a lighthouse beam.

The stars' spin causes their light to appear to pulse. Over their 30-million-year life spans, the pulsation slows gradually, until they finally burn out. [Supernova Photos: Great Images of Star Explosions]

As a pulsar sends radio waves toward Earth, astronomers can measure how fast it is spinning and how it slows down. But when the pulsing stops, the star is essentially hiding.

"When it's off, we literally don't see anything," Camilo said.

Pulsars that have long on again/off again periods allow astronomers to get a peek of what is happening behind the scenes.

By comparing the rotation speed when the star went dark to its speed when it turns back on, researchers can determine the average rate at which the star slowed down while it was unseen, Camilo explained.

Instruments can't capture that information with precision for pulsars that turn off for only a few minutes.

Massive currents in the magnetospheres of the neutron stars provide some of the torque that slows their spin. When the currents stop flowing, the pulsing gradually slows down. But astronomers still don't know what is stopping the currents from flowing.

"These are extremely massive stars — the mass of the sun, jam-packed into the size of a city," Camilo said. "They need a lot of energy to change their rotation. It's something energetic happening near the surface of the pulsar and its magnetosphere."

According to Camilo, information gleaned from PSR J1841 could help astronomers understand how pulsars work.

Furthermore, the discovery hints at the possibility that other known pulsars could be in the midst of their own long "on" period.

Jodrell Bank Observatory in England constantly catalogs known pulsars in the northern hemisphere, and astronomers there have not seen other pulsars vanish after a week or a year, implying that such disappearances are rare.

Camilo notes, however, that pulsars live for 30 million years, while they've only been studied since the 1970s.

"We are just sampling a short portion of [a pulsar's] life," he said.

A pulsar could have an "on" period of a hundred years.

"Some of the pulsars we know and love, and have been studying for 40-odd years, and consider to be reliable standards, maybe one of these years or decades one of them will just turn off."

The detailed findings of the study were published in the February edition of the Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.