Strange Lump of Dark Matter Shouldn't Exist, But Does

A lonely clump of dark matter 2.4 billion light-years from Earth is confounding scientists by its mere presence, researchers say. Contrary to popular astronomy theories, the invisible stuff appears to have been left behind in space after a cluster of galaxies collided.

While the fundamental nature of invisible dark matter remains mysterious, scientists think they have a pretty good idea of how it behaves. For one thing, most galaxies are thought to reside inside larger masses of dark matter, and the two are thought to stay attached, even after cosmic collisions.

Yet this time, it appears the galaxies may have left their dark matter cocoons in the dust.

"This result is a puzzle," astronomer James Jee of the University of California, Davis, said in a statement. "Dark matter is not behaving as predicted, and it's not obviously clear what is going on. Theories of galaxy formation and dark matter must explain what we are seeing."

In the dark on dark matter

Dark matter has never been directly detected; it doesn't reflect light or interact with normal matter except gravitationally. Yet scientists think it dominates the universe, composing 98 percent of all matter in the cosmos.

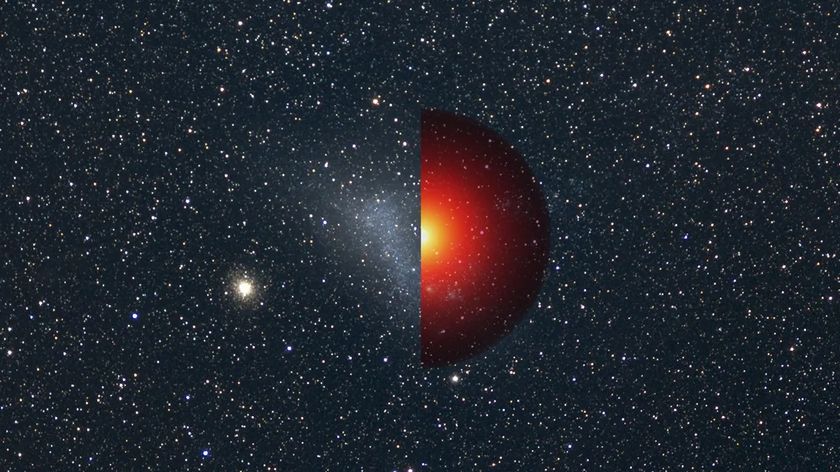

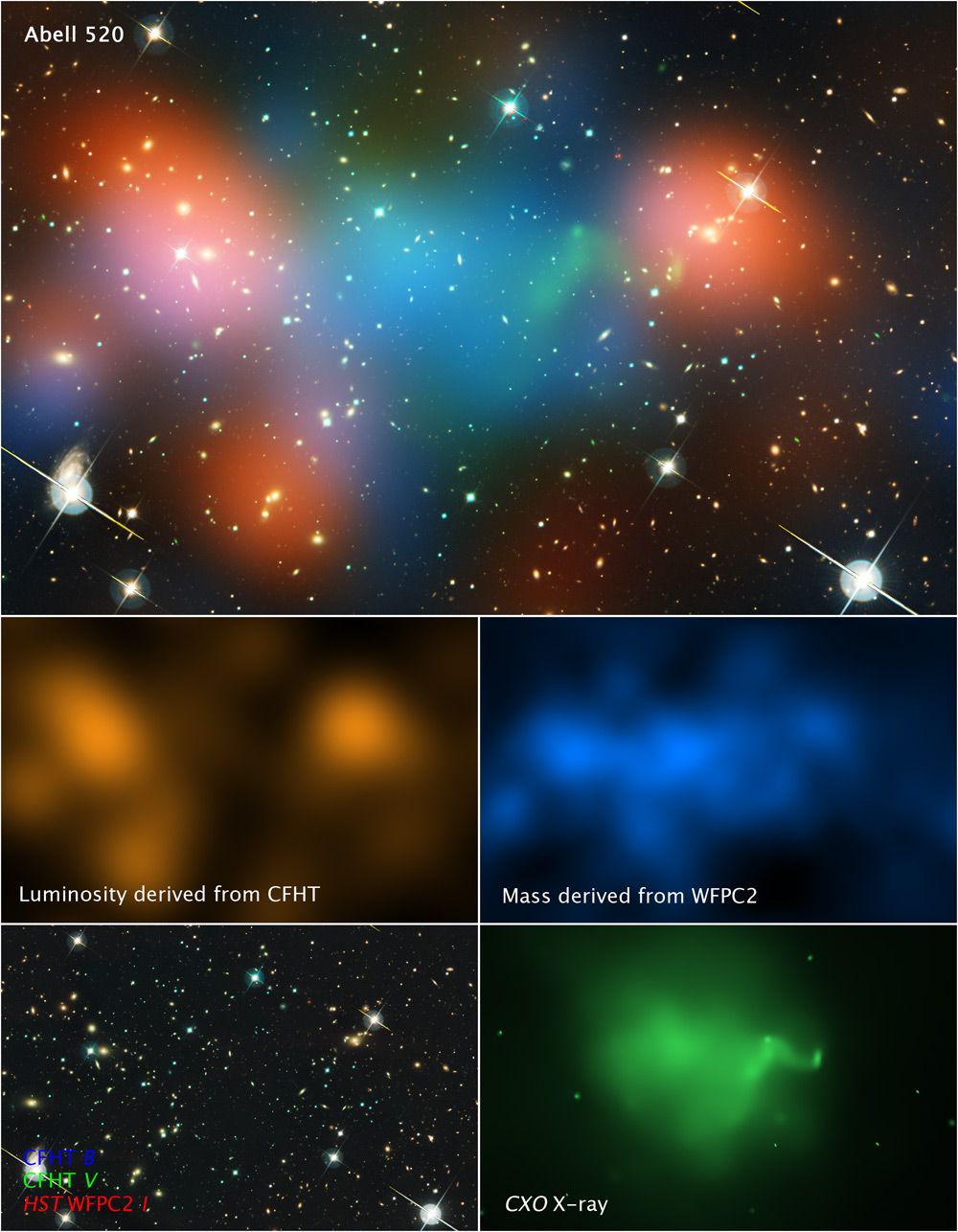

Lee led the team in 2008 that studied the clump of dark matter while using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to investigate the collision of a distant galaxy cluster. The observations were made to follow up on the initial detection of the lone dark matter clump in 2007, which was made bythe Canadian Cluster Comparison Project using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) in Hawaii. [Gallery: Fantastic Hubble Photos]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Canadian Cluster Comparison Project results were not conclusive, so some scientists doubted the strange finding.

"The results were both intriguing and exciting but also engendered justified skepticism, the main criticism being that the clump of dark matter was an artifact of ground-based observations, though we confirmed the CFHT results using observations from the Japanese Subaru telescope," said Arif Babul of the University of Victoria, who led the project.

Now, the new Hubble observations seem to confirm that this clump was abandoned by the galaxies, which belong to a merging galaxy cluster called Abell 520. But astronomers still face the huge challenge of explaining why dark matter is not behaving as expected.

The new findings will be published in an upcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

How to 'see' dark matter

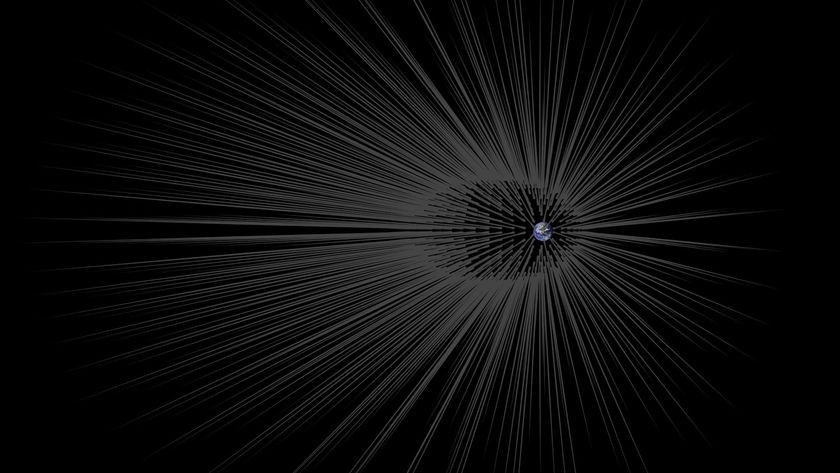

To detect this outlier dark matter blob, astronomers couldn't see it. Instead, they used a technique called gravitational lensing, predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity, which describes how mass bends space and time around it.

That means that when light passes by a massive object — even dark matter — it will travel along a curved path. The researchers were able to calculate how much light from background galaxies was being bent as it traveled past the dark matter clump on its way to Earth.

The observations indicate that dark matter and its interactions with normal matter are even more complicated than experts thought.

"Observations like those of Abell 520 are humbling in the sense that in spite of all the leaps and bounds in our understanding, every now and then, we are stopped cold," Babul said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.