Eyeless Sea Creature Senses Light Like Humans

An eyeless sea creature, related to jellyfish and sea anemones, may nonetheless be able to "see" light and dark, say researchers who found light-sensitive neurons that work in a manner similar to human vision.

"I wouldn’t call this vision, because as far as we know the hydra are not processing information beyond what's light and what’s dark, and vision is much more complicated than that," said study researcher Todd Oakley of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

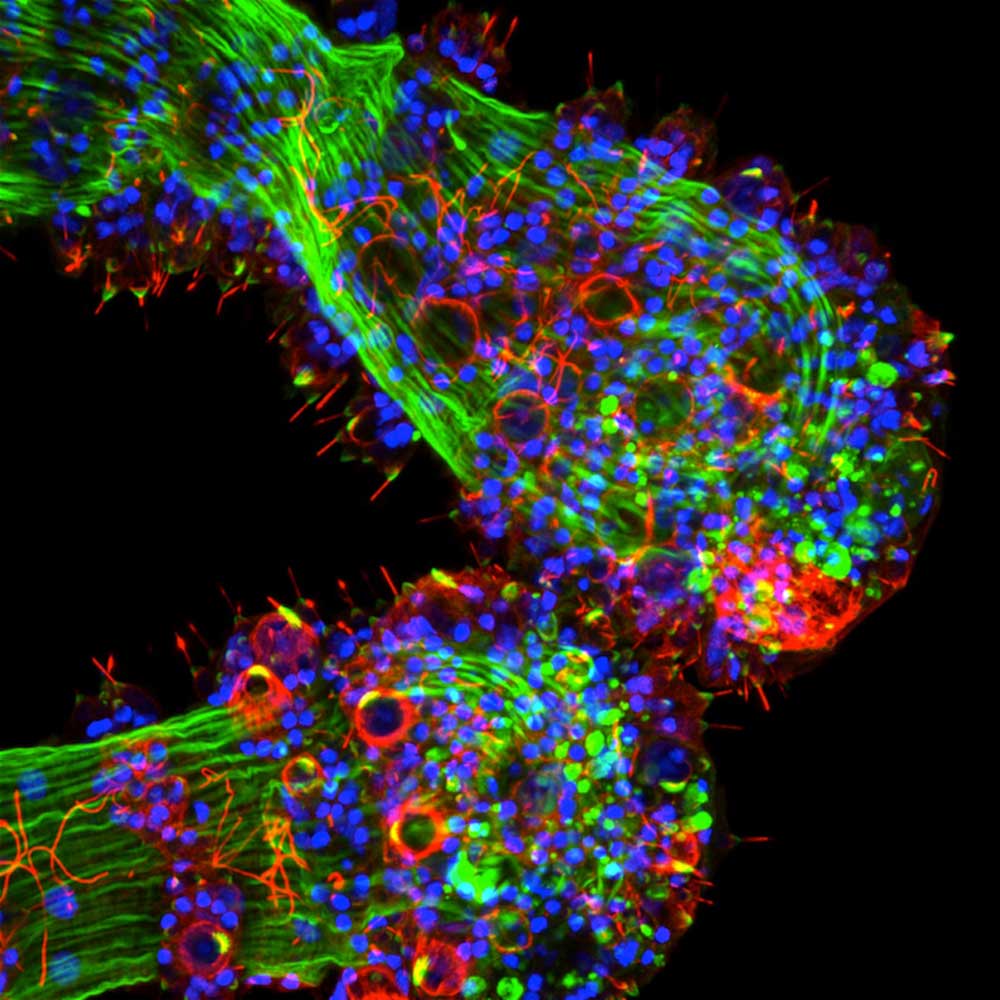

These tiny freshwater polyps called hydra are part of the Cnidaria family, and like jellyfish and other family members sport stinging cells called cnidocytes to help them catch prey. Specifically, the hydra studied (Hydra magnipapillata) has a simple mouth surrounded by tentacles containing barbed cnidocytes, which they use to stun animals like the water flea, before eating them alive. Next to the stinging cells are sensory neurons.

"Hydra stinging cells were already known to be touch-sensitive and taste-sensitive, but no one had ever thought before to look for light sensitivity — probably because they don't have eyes," Oakley said in a statement.

Hydra are simple-looking creatures, under a half-inch (1 centimeter) long and transparent, though this can change depending on the color of the food they have just eaten. They are also somewhat athletic, placing their tentacles on the substrate, before releasing and performing a somersault.

"There is a certain elegance to their movement," David Plachetzki, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Davis, told LiveScience in an interview. "They look like they were designed with an art-deco look to them."

In their study, Oakley, Plachetzki, who at the time was at UCSB, and their colleagues found genes for a light-sensitive protein called opsin inside these sensory neurons, and what's more, they discovered the protein regulates the firing of the polyp's harpoonlike cnidocytes. The whole process is directed by light; the stinging cnidocytes appear to fire less often in bright light versus dim light. [8 Bizarre Creatures on Earth]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They also found these sensory neurons contain the ion channels and additional proteins required to convert light into electric signals, the same process that occurs in the human retina and allows us to see.

The researchers aren't sure why light is the trigger, though they speculate it could have to do with prey, as twilight marks the time when most of their prey comes out to forage.

"Another reason is that there could be a small shadow cast on the tentacles by the prey," Plachetzki noted, suggesting the dimming light would trigger the cnidocytes to fire.

The light cue may also help with their end-over-end somersaulting locomotion, as it could signal that the tentacles are facing the substrate (away from the surface light) to which they need to attach, he added.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.