Powerful Solar Flare May Be Signal of More to Come

An active region on the sun that unleashed a powerful solar flare Sunday (March 4) does not appear to be quieting down, and may have more surprises in store over the coming week, scientists say.

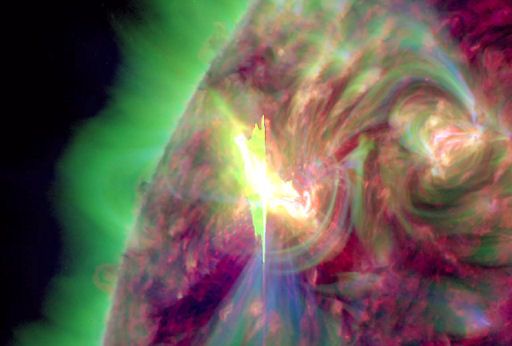

An X1.1-class solar flare erupted from the sun at 11:13 p.m. EST on March 4 (0413 GMT March 5). X-class flares are the most powerful type of solar storm, with M-class eruptions considered to be mid-range, and C-class flares being the weakest.

Sunday's solar tempest sent a fast-moving cloud of plasma, called a coronal mass ejection (CME) hurtling into space. The CME is not expected to hit Earth but could trigger minor geomagnetic storms, according to experts at the Space Weather Prediction Center, which is operated by the National Weather Service.

But while the planet may have been in the clear this time around, more solar storms could be on the way as the sun comes out of an extended lull in activity.

The X-class flare erupted from a massive sunspot region called AR1429, which has been particularly active lately. The sprawling active region is at least five times larger than Earth and could still be growing, said Yihua Zheng, a lead researcher at the Space Weather Center at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

When a powerful X-class flare is aimed directly at Earth, it can sometimes cause significant disruptions to satellites in space and can knock out power grids and communications infrastructure on the ground. Strong flares and CMEs can also be hazardous to astronauts on the International Space Station. [Worst Solar Storms in History]

But as the sun rotates, sunspot region 1429 is shifting closer to the middle of the solar disk. From here, solar flares and CMEs have a more direct path to Earth, and as a result, have the potential to do more damage.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This region has given off an X-class flare, M-class flares and C-class flares, so this region definitely has the potential to spit out something bad," Zheng told SPACE.com. "It has to do with the location on the sun — right now, it's a little bit off where if a CME did hit Earth, it would be a glancing blow."

"There is the potential for more impacts, and this region is rotating from the east limb across the solar disk toward the west, so we're getting closer to the central meridian," Zheng explained. "If something were to erupt there, it would be bad for us on Earth."

Sunspots are temporary patches on the surface of the sun that are caused by intense magnetic activity. These structures sometimes erupt into flares and violent solar storms that send streams of plasma and charged particles into space.

Astronomers closely monitor sunspots because they act as indicators of the sun's activity, which ebbs and flows in an 11-year cycle. Currently, the sun is in the midst of Solar Cycle 24, and activity is expected to ramp up toward the solar maximum in 2013.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.