How the 'Man in the Moon' Turned to Face Earth

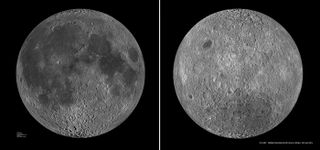

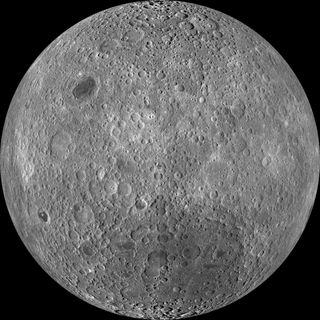

As the moon revolves around our planet, the familiar illusion of a human face etched onto the lunar surface — the so-called "Man in the Moon" — constantly faces the Earth. But there's actually a reason for this arrangement, one that dates back to the moon's creation, and a new study examines why the moon's familiar "face," and not its crater-covered far side, gazes down at us.

The moon orbits Earth in what scientists call a synchronous orbit, which means it rotates exactly once every time it circles the planet. How and why the moon settled into this orbit has been something of a mystery, with some scientists suggesting that the Man in the Moon faces us as the result of mere coincidence.

In the new study, a research team led by Oded Aharonson, professor of planetary science at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif., found that the moon actually turned on its axis faster early in its history, and the rate that the moon slowed before it became locked in its current synchronous orbit likely explains the side that now faces Earth.

While the moon looks like a perfect sphere it is actually elongated, almost like a football. The moon formed a little over 4 billion years ago, and while it was still largely molten, it became stretched by Earth's gravity, the researchers explained.

As the moon cooled, it kept this slightly stretched, oblong shape. Currently, the Man in the Moon is seen on one of the two elongated ends, and this side constantly points toward Earth as the moon rotates around its axis once per revolution around the planet. [Photos: Our Changing Moon]

But, a couple billion years ago, the moon rotated on its axis more rapidly, the researchers said. During this time, people on Earth (if any existed at that time) would have seen all the different sides of the moon at various times.

Over time, Earth's gravity tugged on the moon, slowing its rotation. These tidal forces also created a moving bulge that stayed on the side that was closest to Earth at that moment, the researchers said. The bulge continued to point toward Earth as the moon rotated through it, which churned the moon's interior, causing it to expand and contract as the bulge changed position.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All this internal friction put the brakes on the moon's spin until its rate of rotation matched its revolution rate, locking it into its current synchronous orbit.

By analyzing the physics of the moon, the researchers determined that the rate at which the moon slowed down its spinning determined the side of the moon that points toward Earth.

"The real coincidence is not that the man faces Earth," Aharonson said in a statement. Rather, the bigger coincidence is that the moon slowed its spinning just enough to give the side of the moon with the perceived face a slight edge.

If this change in energy occurred at a different rate — for instance, if the spinning slowed 100 times faster than it did, there would have been a 50-50 chance that the Man in the Moon would face us, the researchers said.

Aharonson and his colleagues used computer simulations to examine these odds. Since the moon's actual rate of dissipation was much slower, the Man in the Moon had about two-to-one odds of facing us, giving it an unexpected advantage.

"The coin was loaded," Aharonson said.

The researchers simulated different scenarios by adjusting the moon's dissipation rate. At times, they were able to make the moon's mountainous far side face Earth, demonstrating the impact of that rate of energy change.

Still, these models are based on the present-day moon. If the moon became locked into its synchronous orbit earlier than in the last billion years or so, the odds found in the new study could be slightly different.

"In the past, when the moon first locked, it could've had different properties," Aharonson said.

The detailed findings of the study were published online Feb. 27 in the journal Icarus.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.