Big Solar Storm Packs Small Punch, But Not Over Yet

A powerful solar storm that slammed into Earth today (March 8) triggered weaker-than-expected disruptions, but may still have a few more tricks up its sleeve, scientists say.

"We're probably not going to see much more from this storm, but I don't know if we can say it's quite over yet," said C. Alex Young, a solar physicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "It might pick up a little bit, but we're not completely certain yet. We still have a bit of time to see if anything else is going to happen."

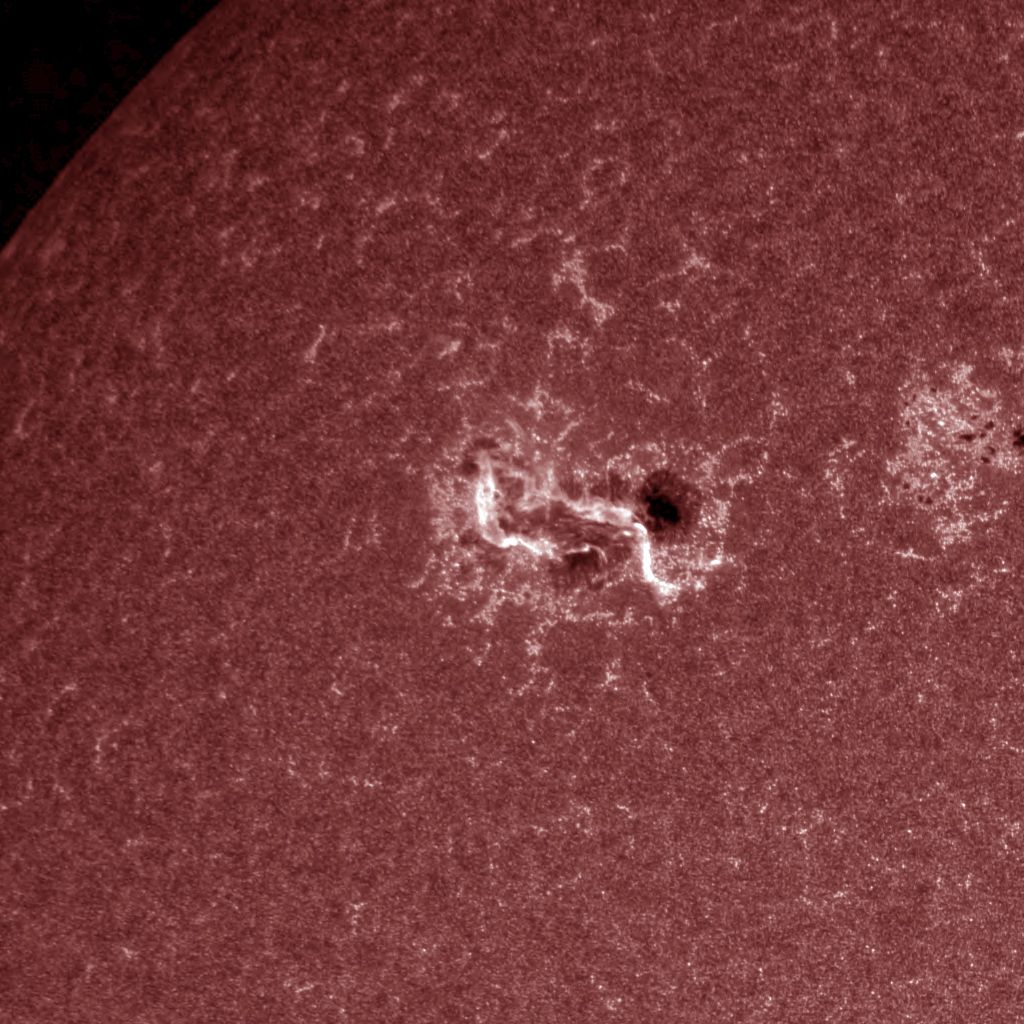

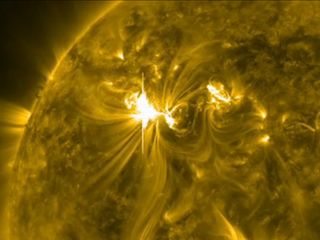

Two huge X-class solar flares (the most powerful type of sun storm) erupted from the sun late Tuesday (March 6), hurling a wave of plasma and energetic particles toward Earth. This blast, called a coronal mass ejection, reached Earth at around 5:45 a.m. EST (1045 GMT) this morning, according to officials at the Space Weather Prediction Center, which is jointly managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service.

Early forecasts showed that the oncoming CME could boost solar radiation in space and trigger geomagnetic storms on Earth, potentially disrupting satellites, power grids and other electronic infrastructure.

But so far, the effects of the solar tempest have been milder than scientists originally predicted, mostly due to the orientation of the CME and Earth's magnetic fields, Young told SPACE.com.

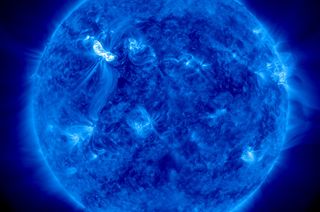

"The orientation of the magnetic field in the CME is a big determining factor for how strong or weak the event is going to be," Young said. "If it's oriented more southward, which is opposite to Earth, then we expect a stronger storm, but it appears that this one was very much north oriented." [Photos: Huge Solar Flare Eruptions of 2012]

Currently, only moderate effects have been felt, but the magnetic field of the CME is dynamic and has the potential to change.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The coronal mass ejection has a cloud of particles, but also embedded in that is a magnetic field structure," said Rodney Viereck, director of NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Test. "As the CME passes over Earth, the magnetic field strength and direction in interplanetary space will change direction and change strength. If that magnetic field direction goes southward, there's good connectivity, and energy in the CME gets translated very efficiently through the magnetosphere to Earth and we get a big storm."

Right now, there are some signs that show the southward part of the magnetic field may be approaching, but it's still too soon to tell, Viereck added.

So far today, no major disturbances have been reported, but several space probes likely experienced high doses of radiation from the onslaught of charged particles. A European spacecraft in orbit around Venus, for example, was temporarily blinded by high radiation, officials at the European Space Agency confirmed today.

Official reports also showed that several commercial airlines, including Delta Air Lines, took caution by re-routing flights that would normally have taken aircraft near or over Earth's polar caps, Viereck said.

"Commercial airlines have diverted some flights away from the poles," he said. "For instance, New York to Beijing — those flights do get diverted because the communication to talk from the cockpit down to the ground can get disrupted by these sorts of events. So, in order to remain in good communication on the ground, they have to skirt around the high latitudes." [Anatomy of Sun Storms & Solar Flares]

These delays are expected to last as long as the level of energetic protons remains high, which could be for another 24 to 48 hours, Viereck said. But, other than flight delays, no other major impacts were recorded, he said.

The energetic particles from the CME are also expected to create amped up displays of auroras (also known as the northern and southern lights) for lucky skywatchers at high latitudes. The light shows, however, will have to compete with tonight's full moon.

"We actually had a geomagnetic storm yesterday from a CME a few days before," Young said. "We saw auroras last night, and yesterday they were as far down as Michigan. Since this geomagnetic storm is not as strong, maybe we'll see something in the northern U.S., but probably not much farther south. We'll certainly see auroras though, and at high latitudes, I'm sure it'll still be pretty spectacular."

And while it hasn't packed much of a punch so far, this ongoing solar storm is the largest one scientists have seen in more than five years.

"The solar storm currently underway is the largest so far during this solar cycle that began about two years ago and is expected to peak 12-15 months from now,"W. Jeffrey Hughes, director of the Center for Integrated Space Weather Modeling at Boston University, said in a statement. "While this is not a major storm, we haven't experienced one this large since the storm that occurred in December 2006 at the tail end of the last cycle."

Space weather experts will continue to monitor the situation, as the effects of the CME are expected to last into tomorrow morning, and the situation could still escalate later today.

Furthermore, the sunspot region that spewed the troublesome flares remains potent, and solar physicists warn that this active region could have more in store.

"It still have a very high potential for producing an X-size flare, so at the moment, there's still a good chance that we're going to see more significant activity from it," Young said.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing photo of the northern lights sparked by these sun storms and would like to share it for a possible story or image gallery, please contact SPACE.com managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.