Fossil of Cuddling Tiny Lobsters Discovered

Fossils of tiny lobsters nestled together in a seashell suggest the fearsome-looking crustaceans were sociable far earlier in their evolution than known.

Modern clawless lobsters often cluster together for shelter, and fossils of extinct clawed lobsters found in Canada suggested these crustaceans might be found together in burrows approximately 70 million years ago.

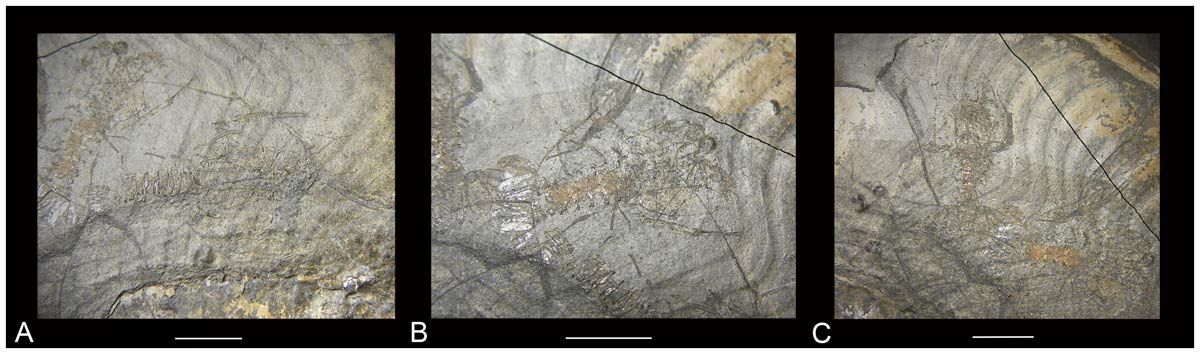

Now a 180-million-year-old seashell found in a rock quarry in southern Germany holds a trio of fossilized lobsters, suggesting that as menacing as the animals might seem, they have long known the value of cuddling up.

"This is the oldest example of gregarious behavior for lobsters in the fossil record ?and not just lobsters but the entire group of decapods, which includes lobsters, crabs and shrimp," said researcher Adiël Klompmaker, a paleontologist at Kent State University.

"What this tells us is that this type of behavior of grouping together may have been very beneficial early on in the evolution of these crustaceans," Klompmaker added.

The translucent, golden-brown seashell in question is a spiral about 9 inches (23 centimeters) in diameter that belonged to an extinct mollusk known as an ammonoid; though they resembled shelled nautiluses, ammonoids were more closely related to living octopuses, squid and cuttlefish. The corpses of the lobsters, each only about an inch (2.5 cm) long, were found side by side more than halfway into the spiral within the outermost whorl. The tiny lobsters could be seen through the shell.

"It's a unique specimen — it's one of a kind in the world," Klompmaker told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers suggest the lobsters may have sought temporary shelter in the ammonoid to hide from predatory fish or to prepare to molt their shells. Alternatively, they may have been feasting on the ammonoid's meat or living together in the shell as a long-term home.

"In this particular locality, there's not a whole lot to be found on the bottom of the ocean — no rocks, no nooks and crannies — and the muddy bottom there was probably not suitable for burrowing, so pretty much the only place to go to for defense against predators would be within these large ammonoid shells," Klompmaker said.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 7 in the journal PLoS ONE.