Slam Dunk! Why Giant Squid Sport Basketball-Size Eyes

Updated at 8:44 a.m. ET, Monday, 3/19

The enormous eyes of giant and colossal squid may help them spot predatory sperm whales in their dim undersea habitat, a new study finds.

These mysterious squid are tough to spot and even tougher to study in their natural habitat. But squid that have been caught or observed have huge, basketball-size peepers — three times the diameter of another other animal, including behemoths of similar size, such as swordfish.

"It doesn't make sense a giant squid and swordfish are similar in size, but the squid's eyes are proportionally much larger, three times the diameter and 27 times the volume," study researcher Sönke Johnsen, a biologist at Duke University, said in a statement. "The question is why. Why do giant squid need such large eyes?"

Where'd you get those peepers?

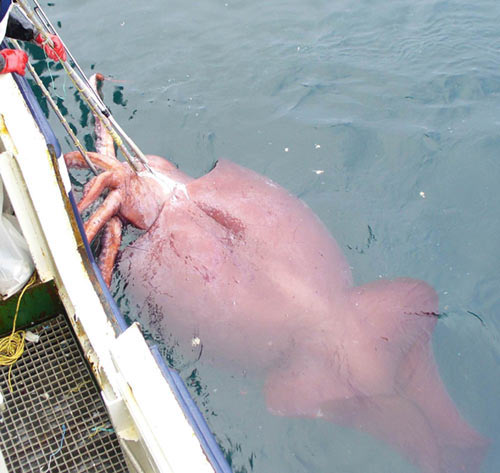

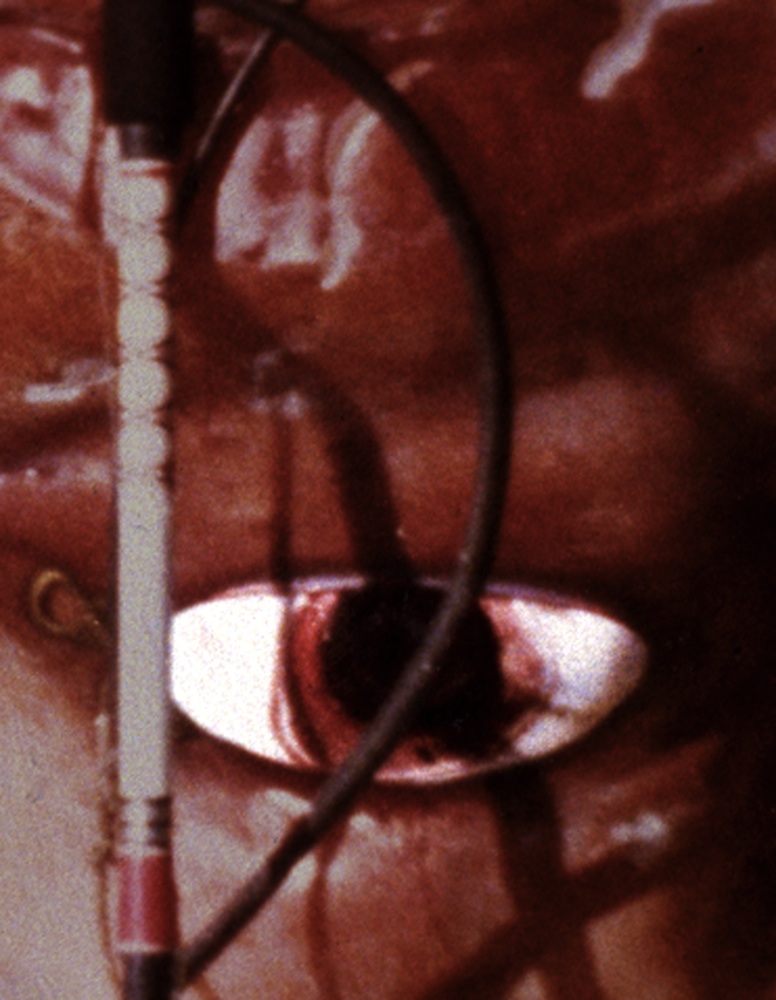

To find out, Johnsen and her colleagues first had to confirm the eye size of these elusive creatures, because most eye size reports were based on anecdotes. They obtained photographs of the eye of a freshly caught giant squid and were able examine the corpse of a colossal squid, an even larger species, from New Zealand. [Gallery: Stunning Squid]

The examinations confirmed the squid eyes can get up to 10.6 inches (27 centimeters) in diameter. The pupils in these dinner-plate-size orbs are 3.5 inches (9 cm) across.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With this information, the researchers were able to mathematically model how well the squid is able to see in their deep-ocean habitat. They found that such giant eyes are usually a waste. At a size bigger than an orange, eyes take more energy to grow and maintain than they return in vision benefits, study researcher Dan-Eric Nilsson of Lund University said in a statement. But giant eyes do allow more light in, enabling an animal to detect lower levels of contrast in their dim environment.

Dangerous glow

This ability wouldn't matter much to a fish, but giant and colossal squid are in a unique situation, Nilsson, Johnsen and their colleagues report today (March 15) in the journal Current Biology. Their major predator is the enormous sperm whale. The whales are huge, but at a distance in the dim ocean light, the only hint that one might be coming is the bioluminescence given off by ocean plankton dispersing as a whale swims through and disturbs them. It's this bioluminescence that might be the key to squids' giant eyes.

"It's the predation by large, toothed whales that has driven the evolution of gigantism in the eyes of these squid," Johnsen said.

With eyes the size of basketballs, the squid can detect the faint light of a moving sperm whale from a distance of about 394 feet (120 meters), more than the length of an American football field including end zones. That may be enough time to plan an escape, the researchers said.

The study is speculative, as interactions between sperm whales and giant squid aren't easy to observe. In fact, researchers had never even seen a live giant squid in action until 2005, when Japanese scientists managed to capture one on video. But the researchers say their new model is a step forward in understanding how undersea creatures see.

"It is a powerful tool for understanding vision," Nilsson said.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to correct a metric conversion. The giant squid can detect a sperm whale from a distance of 394 feet, not 294 feet as we had stated earlier.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.