Movie Packs Virtual Birth of Universe into Mere Minutes

To be sure, director Terrence Malick's "The Tree of Life" is a very pretty picture. So much so, its Oscar nomination for best cinematography caps a long list of awards the film has garnered since its preview at Cannes last May, including bests from the American Society of Cinematographers, BAFTA, Golden Globes, New York Film Critics and dozens more.

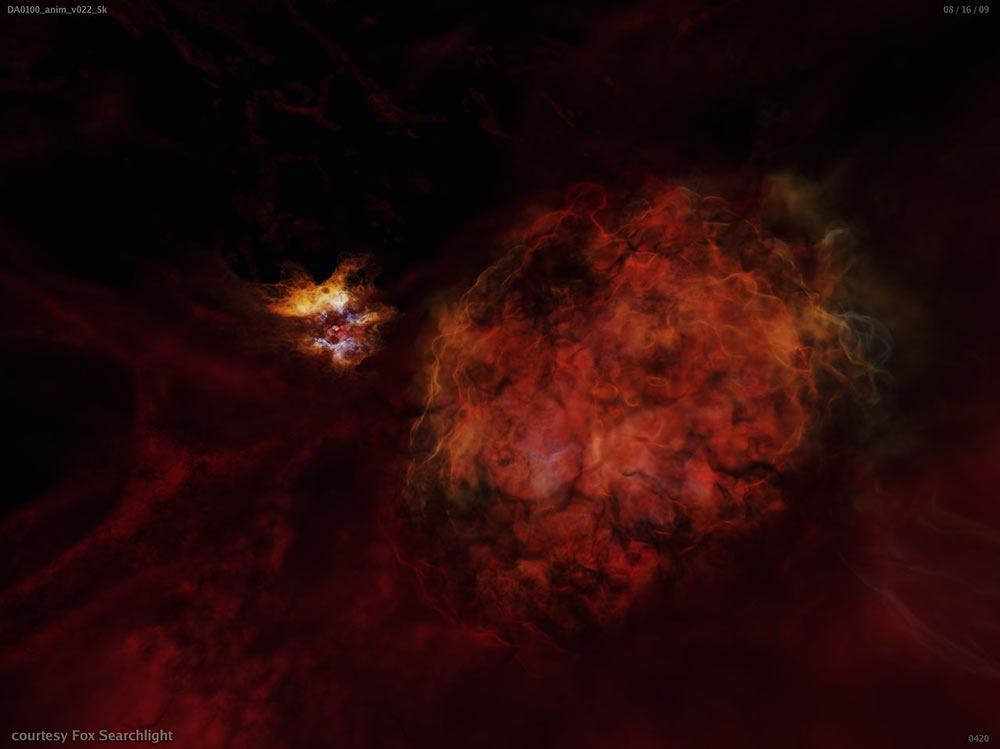

Starring Brad Pitt, Sean Penn and Jessica Chastain, "Tree" contains many visually lush scenes from mid-20th century Americana shot mostly on film with a single hand-held camera. And in what Fox Searchlight Pictures calls "images largely unseen in the pantheon of motion-picture history," Malick, photography director Emmanuel Lubezki, and effects specialist Dan Glass inject into a dramatic narrative a stunning amount of science and natural history not typically seen in the local multiplex.

Although the film didn't win an Academy Award this year, such depictions mark a trend by moviemakers and other entertainment producers to present science, engineering and natural phenomena with as much realism as current knowledge and production budgets allow.

In a few short minutes, we witness the formation of the universe 14 billion years ago: the formation of Earth from solar nebulae accretions; writhing molecules that turn into life forms; the reign of the dinosaurs (and their demise); and the fate of the universe billions of years hence when our sun is but a white dwarf and our Earth merely aimless planetary fragments.

No human being was — or will be — present for any of that, mind you, which left the filmmakers much creative license. Instead, they chose to portray those unknowable events "right," says astronomy professor Volker Bromm, whose prodigious data crunching at the Texas Advanced Computing Center in Austin has produced some of cosmology's best understanding of star formation.

"He didn't want to just make up stuff. He wanted to do the real thing," Bromm says of his first interactions with Malick.

Professor David Kirby, author of "Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists and Cinema," refers to such realistic imagery as powerful opportunities for "virtual witnessing." That is, through such depictions, the viewing public can experience scientific discovery the same way a scientist does. Cinema's virtual-witnessing capacity, he says, "has the potential to significantly impact — positively or negatively — our perceptions of the natural world and science as a cultural endeavor."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not far from where much of "The Tree of Life" was shot, Bromm had been using vast amounts of bandwidth to model conditions that led the universe out of the cosmic Dark Ages and into "first light," as they call it. "We start with the box that represents the entire universe, and then we put in all of the known laws of physics, and then we get to the point where the original stars form," said Bromm, whose Scientific American article about the subject caught Malick's attention.

So over some 42 days, Bromm and the TACC supercomputer known as "Ranger" whirred through a "humongous degree of complexity" to produce a simulation as close as humanly possible to how the first stars were actually born.

“The closest we can come is a computer simulation of the universe because at this point we cannot directly observe it,” Bromm said. “It's remarkable the kind of realism we can create with a computer.”

"Terry had read and read and had a phenomenal level of knowledge about our current understanding in these areas," said Glass. "He had contacted world experts, and it was very important to him that in the midst of trying to make beautiful, emotional imagery that it also represents the latest scientific theories."

That commitment also led Malick and Glass to Donna Cox, a senior scientist (and art professor) who leads the Advanced Visualization Laboratory at the University of Illinois' National Center for Supercomputing Applications. For more than two decades, Cox and her AVL colleagues have created high-resolution cinematic visualizations of real scientific data generated by supercomputers. Such terabyte images support scientific theories about natural phenomena — from cosmology to cell biology to extreme weather — that can best (and sometimes only) be experienced and interpreted through such detailed visualizations.

Much of AVL's work has appeared in full-dome planetarium productions, IMAX theaters and on documentary television. "Tree" marks their first work in a feature film and perhaps the first time a scientific supercomputer simulation has appeared in a feature.

"I don't think I've ever seen any director try to authentically render the beginnings of the universe in a feature film before," said "Tree" co-producer Dede Gardner.

For months the group enlisted a cluster of dedicated computers using about 200 processors. When that wasn't enough, they turned to "Abe," NCSA's now-retired 9,600-processor supercomputer.

In the end, the team, which included Stuart Levy, Alex Betts and Bob Patterson, handed over highly detailed visualizations of a galaxy model created at NCSA and Bromm's first-starlight model generated at TACC. The London-based company Double Negative Visual Effects, well-known for their special-effects work on blockbuster films, added further elements to make the final composite.

The animations appear for about a minute of the 139 in the cinema release, which showed in only a couple hundred movie houses. Still, "getting the science onto the big screen is a wonderful multiplier," said Bromm. "It nicely resonated with our interests as scientists to make our work relevant for the public and making it understandable."

Both NCSA and TACC are supported by the National Science Foundation.