Despite Fuel Crisis, Fossett Heads Across Pacific Ocean

Officials: Fuel 'Simply Disappears'

A plane attempting the first around-the-world, non-stop, solo flight is running out of fuel as it crosses the Pacific Ocean on its final leg.

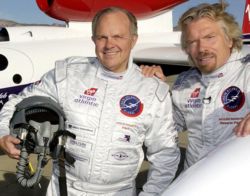

Adventurer and aviator Steve Fossett has passed the half-way point in his quest to fly the Virgin Atlantic's GlobalFlyer into the record books. But mission control at the plane's departure and landing site in Salina, Kansas, has confirmed that the fuel onboard "appeared to be drastically lower than was expected at that point in the record attempt."

The mission's objective hangs in the balance.

Checks and rechecks

There are two ways of reading fuel load onboard the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer: fuel-burn sensors and fuel probes in the tanks.

After a long and exhausting night of checks and rechecks, fuel burn sensors and probes were showing "significant discrepancies," explained a Virgin Atlantic update made available to LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Discussions between Fossett and mission control have led to a throat-gulping realization:

Early fuel indications had not given an accurate reading on the actual amount of fuel onboard. In fact, the lower of these two readings, from the probes, were the accurate indicators.

It is not yet clear whether the problem is due to the gauge incorrectly indicating the amount of fuel onboard or if it was a loss of fuel due to leakage.

Fuel "simply disappeared"

The aircraft took off with a hefty load of fuel, 18,100 pounds, and it appears that within the first 3.5 hours of flight 2,600 pounds of fuel "simply disappeared," according to a press statement today.

Currently the fuel onboard, at just over the half-way mark of the around the globe sojourn, is estimated to be 5,500 pounds.

Now under investigation are a variety of scenarios to get Fossett and the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer back home to Salina, Kansas safely and still winging to a landing with a world record in hand.

One alternative is routing the high-flying craft further south. The second prospect is to continue with the current route, relying on the speed of the jet streams across the Pacific - a tactic that maximizes remaining fuel. But this approach means Fossett will be at the mercy of the winds.

Decision ahead: go/no go?

Later today, the GlobalFlyer team will have to decide if it's go or no go when the aircraft reaches the coast of Japan. At that point the plane begins the long journey across the largest ocean in the world - the Pacific.

"This is huge set back. To think we might not have enough fuel for the remainder of the flight," radioed Fossett to mission control.

The is not Fossett's first global adventure. In 2002, he navigated around the world in a balloon. He holds records in aviation and sailing.

"I immediately started to think of alternatives, possibly a route over Mexico for example or how far I could glide," he said. "I have not that high a level of confidence at this point. There are still significant hurdles to overcome - not least being the fact that the success of this flight is now down to the calculation of the winds. Also the fear that unforeseen problems in the fuel redistribution from the tips of the wings, which we have yet to undertake...is a worry," Fossett radioed.

Jon Karkow, chief engineer for the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer aircraft, explained:

"This issue is extremely concerning as it will be weighing heavily on Steve's mind and has put the record attempt in jeopardy," Karkow explained. There are grueling hours ahead, he added.

GlobalFlyer was engineered by Burt Rutan, the man behind SpaceShipOne, which last year won the Ansari X Prize for suborbital flight. The new plane is financed by Sir Richard Branson, chairman of Virgin Atlantic.

UPDATE: On to Hawaii

March 2, 9:14 p.m. ET

In the event that Fossett and GlobalFlyer mission control decide on sailing past Honolulu, an estimated flight time of seven hours would be ahead in reaching Los Angeles, California.

According to a GlobalFlyer web site update, the first available airstrip beyond Honolulu is 2,610 miles away and located on Catalina Island - some 22 miles off the coast of Southern California. Fossett will have the final say in deciding to abort the around-the-globe flight, or continuing onward.

He has radioed to mission control in Salina, Kansas saying that while "confidence isn't the right word to use right now," he did say, "I'm hopeful that it's all going to work out."

There has been some discussion about whether Fossett would be able to gilde to safety were he to run out of fuel. GlobalFlyer was built to be able to glide well, having a glide ratio of about 200 miles. However, until Fossett reaches Hawaii, any further decision making is on hold.

March 2, 4:21 p.m. ET

Steve Fossett has decided to cross the Pacific Ocean at least as far a Hawaii. As the aircraft reaches Hawaii airspace, a decision could be made to abort the attempt.

On the other hand, a blend of tailwinds and the slowing GlobalFlyer's flight speed to conserve fuel, could add up to pressing forward on the record-setting, globe-circling trek. The pumping of fuel between tanks is ongoing.

The plane's wing tip tanks have been drained and the pumping of fuel from the mid-wing tanks is underway.

Flying at nearly 45,000 feet, Fossett's view is that he was still "very hopeful" of making it back to Salina, Kansas - the start of his world-circling voyage.

On the GlobalFlyer's web site, Sir Richard Branson, who is backing the venture, noted: "I think it's too soon to be confident that he'll make it all the way around the world... I think by the time he reaches Hawaii we'll have a pretty good idea of whether he'll make it."

Credit: Virgin Atlantic

The Big Questions: Food, Rest and Pee

For three days prior to the flight, pilot Steve Fossett was on a low-residue diet high in protein to ensure nothing upsets his digestive system and to avoid mid-air bowel movements. He has onboard a supply of diet milkshakes and a bottle to pee in.

Fossett will get "simulated rest" by staying very relaxed and still.

"I know how to relax and I also know that when I'm not getting much physical exercise, I don't need much sleep," he says. "On two occasions -- while ballooning and sailing -- I've been awake for just over three days."

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years.