Sending a submarine to the bottom of the ocean on Jupiter's icy moon Europa is the most exciting potential mission in planetary science, according to one prominent researcher.

Europa's seafloor may well be capable of supporting life as we know it today, said Cornell University's Steve Squyres, lead scientist for NASA's Opportunity Mars rover, which is currently roaming the Red Planet. So a Europa submarine mission is at the top of his wish list, though it likely won't happen anytime soon.

"This is fantastic stuff," Squyres said Wednesday (March 21) at a conference called Nuclear and Emerging Technologies for Space in The Woodlands, Texas. "This is the holy grail of planetary exploration right here."

A habitable environment?

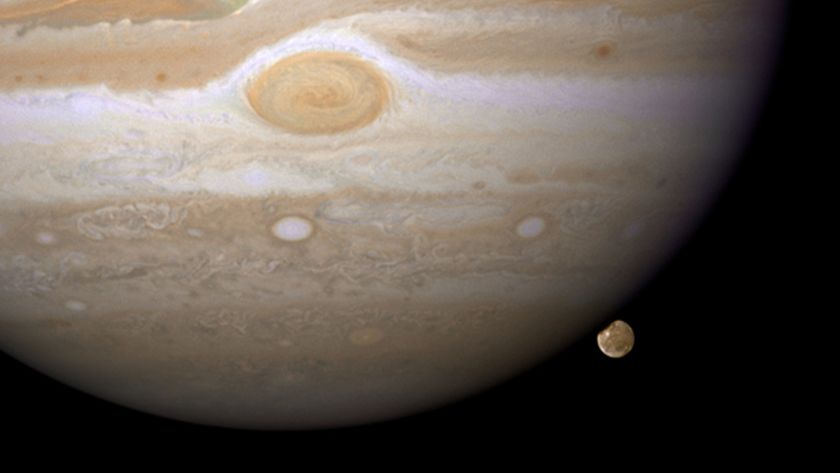

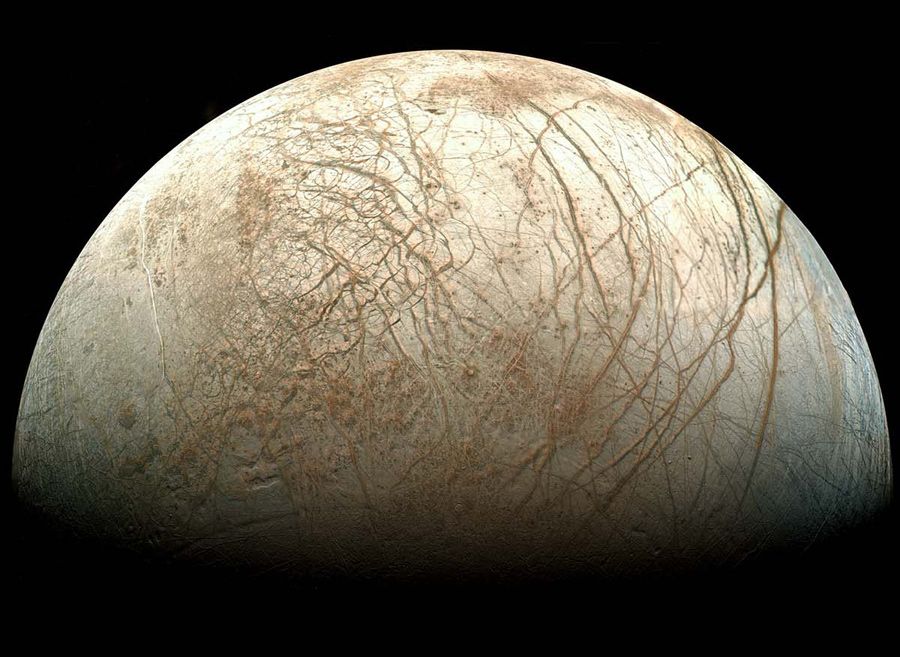

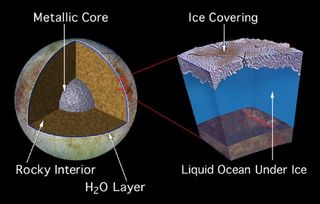

Many planetary scientists regard Europa, which is slightly smaller than Earth's moon, as the solar system's best bet for harboring life beyond Earth. That's chiefly because Europa appears to have a huge ocean of liquid water sloshing around beneath its icy shell. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

Here on Earth, all life needs to gain a foothold is liquid water and an energy source. Europa likely boasts both, with hydrothermal vents gushing from the seafloor as they do on our planet, researchers say. And Earth's deep-sea vent systems host vibrant ecosystems.

"You do the calculations for Europa, and what you find is that there ought to be hydrothermal activity; there ought to be volcanic activity at Europa's seafloor," said Squyres, who recently chaired the U.S. National Research Council's Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which lays out the scientific community's goals for planetary science over the next 10 years.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a chance to search for a potentially habitable environment today on another world," he added.

A tough mission

A Europa submarine mission didn't make the Decadal Survey's list; it's just not feasible at the moment. If scientists want to tackle it, they'll have to overcome some serious technical and engineering challenges — such as how to get through Europa's icy crust.

"This is one of the hardest missions you can imagine," Squyres said. "You need a power system that will enable you to get onto the surface. You then have to some way find your way down through what might be 10 kilometers of ice. And then you have to release some kind of free-swimming vehicle that is able to go down to the bottom of that ocean and find out what's down there."

The Decadal Survey did value a mission called the Jupiter Europa Orbiter (JEO) highly, ranking it the number two priority among multibillion-dollar "flagship" possibilities (number one was a Mars sample-return effort). JEO would study the icy moon from above; it, or something like it, could help pave the way for an eventual submarine mission, researchers say, by identifying thin patches in the moon's icy shell.

But with an estimated price tag of $4.7 billion, JEO is not likely to get off the ground in the near future, either. In his 2013 budget request, which was released last month, President Barack Obama allocated just $1.2 billion to NASA's planetary science efforts. That's a 20 percent cut from the current allotment of $1.5 billion, and further reductions are expected over the next several years.

As a result, NASA has temporarily shelved its plans for future flagships to other planets and planetary systems, saying it just doesn't have enough money to make them work. The space agency will continue actively planning cheaper missions, and it will be ready to restart flagships if the funding situation improves, officials have said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.