Coldest, Deepest Ocean Water Mysteriously Disappears

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The coldest deep ocean water that flows around Antarctica in the Southern Ocean has been mysteriously disappearing at a high rate over the last few decades, scientists have found.

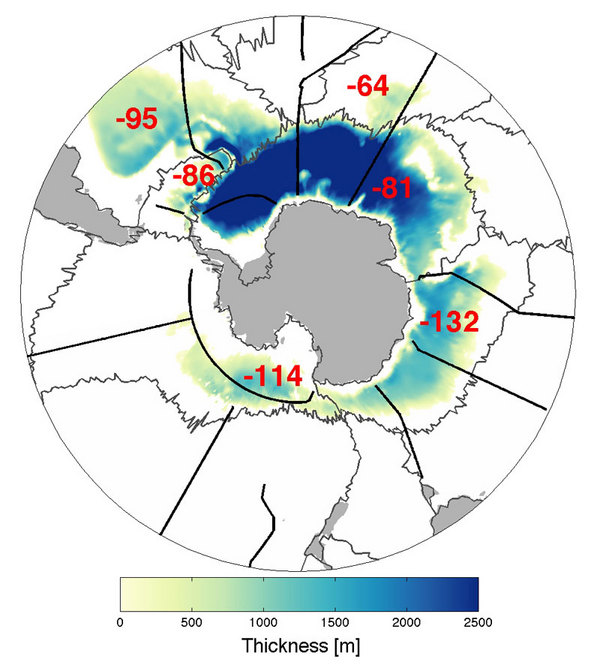

This mass of water is called Antarctic Bottom Water, which is formed in a few distinct locations around Antarctica, where seawater is cooled by the overlying air and made saltier by ice formation (which leaves the salt behind in the unfrozen water). The cold, salty water is denser than the water around it, causing it to sink to the sea floor where it spreads northward, filling most of the deep ocean around the world as it slowly mixes with warmer waters above it.

The world’s deep ocean currents play a critical role in transporting heat and carbon around the planet, which helps regulate the Earth's climate.

Previous studies had indicated that this deep water has become warmer and less salty over the past few decades, but a new study has found that significantly less of this water has also been formed during this time.

Oceanographers examined temperature data collected from 1980 to 2011 at about 10-year intervals by an international program of repeated ship-based oceanographic surveys in the Southern Ocean.

They found that Antarctic Bottom Water has been disappearing at an average rate of about 8 million metric tons per second over the past few decades, equivalent to about 50 times the average flow of the Mississippi River, according to statement from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which helped fund the data collection.

"In every oceanographic survey repeated around the Southern Ocean since about the 1980s, Antarctic Bottom Water has been shrinking at a similar mean rate, giving us confidence that this surprisingly large contraction is robust," said lead author of the study Sarah Purkey, a graduate student at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's causing the reduction and what it means are things the researchers must still investigate.

"We are not sure if the rate of bottom-water reduction we have found is part of a long-term trend or a cycle," said co-author Gregory C. Johnson, an oceanographer at NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle.

Changes in the temperature, salt content, dissolved oxygen and dissolved carbon dioxide of this prominent water mass have important ramifications for Earth's climate, including contributions to sea level rise and the rate of Earth's heat uptake.

"We need to continue to measure the full depth of the oceans, including these deep ocean waters, to assess the role and significance that these reported changes and others like them play in the Earth's climate," Johnson said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus