How Cellulose Could Make Fibers As Strong As Steel

People have long used cellulose — the indigestible, woody fibers in plants — to make paper, but one group of scientists is looking to make cellulose items that are a little more sophisticated. On March 25, materials scientist Olli Ikkala presented one cellulose-based material he made that's almost as strong as steel and another that can float while carrying cargo 1,000 times its own weight. He was part of a round of presentations dedicated to cellulose at the American Chemical Society's national meeting in San Diego.

People are interested in sustainable and renewable things, Harry Brumer, a chemist at the University of British Columbia, said during a press conference. So he and his colleagues thought this was the right time for a scientific meeting about some of the most abundant, renewable stuff on Earth. Ikkala is especially interested in cellulose as a future replacement for petroleum, which is a key ingredient in everything from plastics to tire rubber. "It's going to happen sooner or later that the oil-based materials become—the price becomes less and less competitive," he said during the conference.

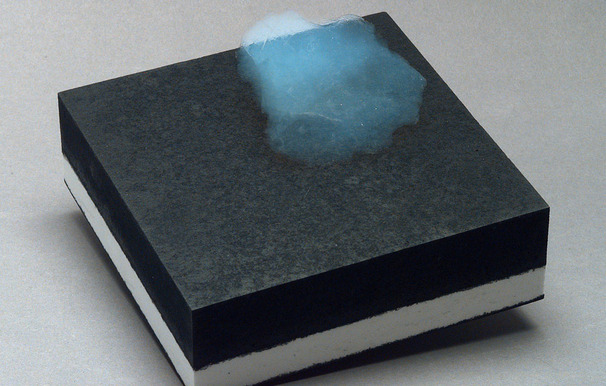

In 2010, Ikkala, who researches at Helsinki University of Technology in Finland, and several colleagues published a way of making an extraordinarily light, porous material called an aerogel out of cellulose produced by bacteria. They found that cellulose makes a flexible aerogel, unlike other aerogels, which are stiff and can't bend. They also magnetized the material in a bath of cobalt and iron. The material could be used in electronics and in industrial devices that need to control tiny amounts of fluid, they wrote.

Since then, they've worked to make other interesting versions of their aerogel, which is comprised of tiny, nano-size fibers of cellulose.

They have created a material that repels water, which could be used for self-cleaning surfaces and to make surfaces that don't accumulate ice.

They combined the aerogel with graphene, carbon arranged in a layer one atom thick. The result was a material whose strength is "in the range of steel, or even higher than some grades of steel," Ikkala told InnovationNewsDaily during a phone call before the press conference started. He presented about the material at the American Chemical Society conference and is in the process of publishing his findings from that experiment, he said.

In 2011, his team covered the aerogel's cellulose fibers with titanium dioxide, which repels water but absorbs oil. Such a material could work like a "diaper" for absorbing oil spills, he said. They made the diaper-style material extremely buoyant, so workers could float it on spill-polluted waters to clean up the oil. Afterward, cleanup crews could collect the oil for reuse or burn it.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists have long been interested in reproducing nature's materials and fabrics, such as spider silk, which researchers are interested in for its strength, flexibility and low weight. "The problem in those materials is that the biosynthesis is extremely slow," Ikkala told InnovationNewsDaily. Besides his cellulose work, he is trying to find faster, easier ways of reproducing silk and nacre, the material that oysters use to make pearls.

Though the eco-friendly materials he studies aren't ready for consumer products yet, people are likely to see nature-inspired materials in a few years, Ikkala said. "This is an ongoing and extremely important field to make lightweight construction materials, but it's still in progress."

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily staff writer Francie Diep on Twitter @franciediep. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.