Black Hole Beyond Our Galaxy Looks Surprisingly Normal

A relatively "ordinary" black hole has been discovered in a distant galaxy, in what is the first time that a low-mass black hole has been found so far beyond our own Milky Way, scientists say.

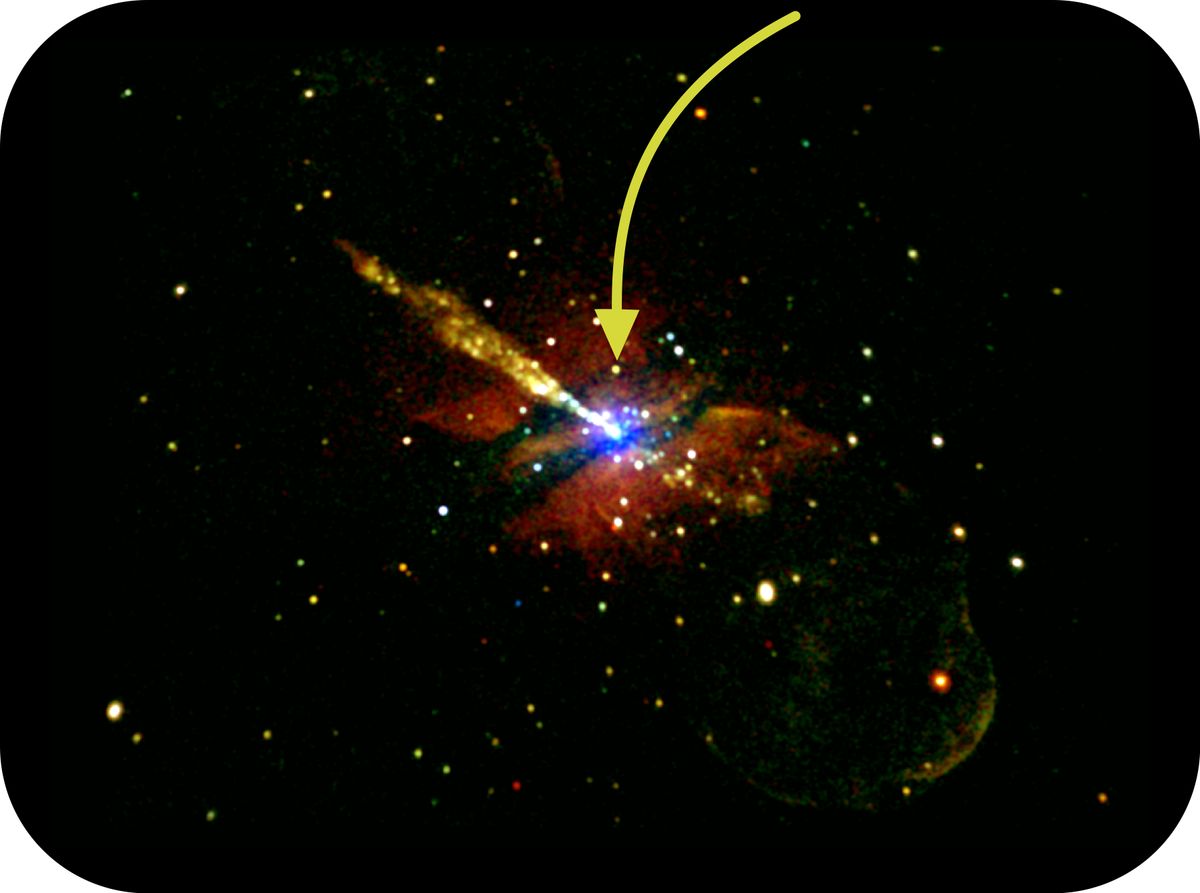

An international team of researchers detected a so-called "normal-size" black hole in the distant galaxy Centaurus A, which is located about 12 million light-years away from Earth. By observing the black hole's X-ray emissions as it gobbles material from its surrounding environment, the scientists determined that it is a low-mass black hole, one likely in the final stages of an outburst and locked in a binary system with another star.

The object is typical of similar black holes inside our Milky Way galaxy, but the researchers' observations suggest that this is the first time that a normal-size black hole has been detected so far beyond the vicinity of our home galaxy. Its discovery gives astronomers the chance to characterize the population of black holes in other galaxies, they said.

"So far we've struggled to find many ordinary black holes in other galaxies, even though we know they are there," Mark Burke, a graduate student at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., said in a statement. "To confirm (or refute) our understanding of the evolution of stars we need to search for these objects, despite the difficulty of detecting them at large distances." [Photos: Black Holes of the Universe]

Burke is presenting the discovery at the U.K.-Germany National Astronomy Meeting, which is being held this week in Manchester, England. He was part of an international team of astronomers led by Ralph Kraft of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

The researchers used NASA's orbiting Chandra X-ray Observatory to make six 100,000-second long exposures of the galaxy Centaurus A.

Their observations unearthed an object with 50,000 times the X-ray brightness of our sun, but a month later, it had dimmed by more than a factor of 10. Later, it had dimmed even more, by a factor of more than 100 to become undetectable, the researchers explained.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This type of behavior is typical of similar black holes in the Milky Way, but also indicates that the object is likely in the final stages of an outburst.

Black holes can't be seen, but astronomers can observe their surrounding activity to find them. The lowest-mass black holes are formed when very massive stars reach the end of their lives and eject most of their material into space in a violent supernova explosion. This blast leaves behind a compact core that collapses into a black hole.

Scientists estimate that there may be millions of these low-mass black holes distributed throughout every galaxy, but they are hard to detect because they do not emit light. Astronomers detect them by observing activity around them, such as when black holes drag in material, which is then heated and emits X-ray light.

Still, an overwhelming majority of black holes remain undetected. In recent years, researchers have made some progress in discovering ordinary black holes in binary systems. Scientists look for the X-ray emission produced when they siphon material from their companion stars.

So far, these detections have been relatively close in astronomical terms, either inside the Milky Way galaxy or in a cluster of nearby galaxies known as the Local Group. The low-mass black hole found by Burke and his colleagues opens up the opportunity for astronomers to better understand the black hole population of other galaxies.

The team now plans to examine more than 50 other bright X-ray sources within Centaurus A to either identify them as black holes or other exotic, luminous objects.

"If it turns out that black holes are either much rarer or much more common in other galaxies than in our own it would be a big challenge to some of the basic ideas that underpin astronomy," Burke said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.