Take an Anatomical Safari: Photos of Inside-Out Animals

Anatomical Safari

Gunther von Hagens, creator of the controversial yet wildly popular Body Worlds exhibit, has taken his penetrating vision to the world of non-human animals, big and small, with his new exhibit "Animal Inside Out" at the Natural History Museum in London. The exhibition is an anatomical safari under the skin of some of nature's most impressive creatures. Take this muscle-y elephant, for instance, one of the giants of the show.

"Usually you see our specimens as skeletons, stuffed animals or preserved in alcohol," Georgina Bishop, exhibition developer at the museum, said in a statement. "At Animal Inside Out, visitors will see animals close up in a whole new way and in the most amazing detail as they get under the skin of some of nature's most incredible creatures." Take a look at some of the highlights.

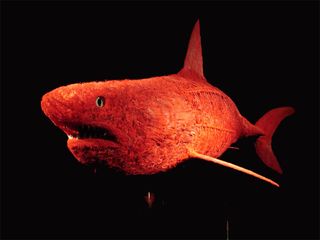

Glowing Shark

During the plastination process colored liquid resin is injected into the animal's main arterial network. When the surrounding tissue is removed a perfect highway of vessels is revealed. Here, a surreal-looking porbeagle shark (a type of mackerel shark), which will greet visitors of the exhibition, has had its skin removed to show the intricate blood system underneath.

Charge!

Like this bull, all the animals in the exhibit have been plastinated by the Body Worlds team. Von Hagens invented the process at Heidelberg University in 1977. There are, however, always new challenges such as plastinating this powerful bull, which can weigh up to 2,645 pounds (1,200 kilograms).

Reindeer Run

A reindeer's body shape not only helps it cope with the harsh arctic conditions, it also helps them to survive attacks from predators. The muscles that power the legs are mounted close to the trunk, keeping the ends of the legs nice and light.

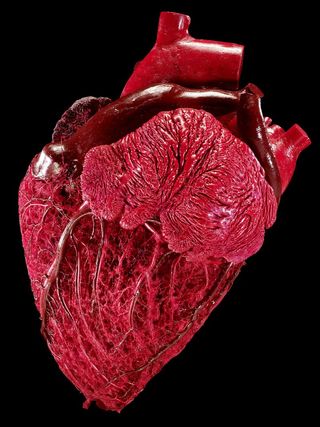

Hefty Heart

Tiny or towering, a mammal's size can affect how long it lives for: a tiny shrew whose heart races at 1,000 beats a minute lives for just a few years, while the slow-beating heart of an elephant can beat for up to 70 years.

For instance, a bull's heart is packed with blood to circulate around the large beast; as such, it weighs about 5 pounds (2.25 kg), making it five times heftier than a human heart. The coronary arteries of a bull’s heart run along the outside of it, with smaller vessels that penetrate the wall.

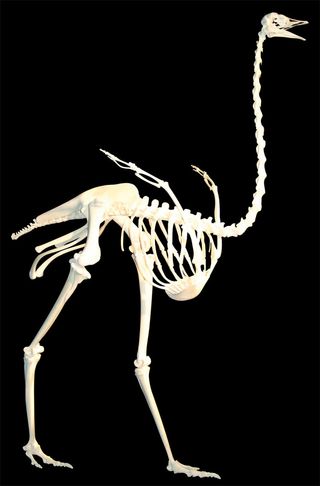

You're Grounded!

The ostrich is a bird that's too heavy to fly, with an adult weighing up to a whopping 352 pounds (160 kilograms), about twice that of a large man.

Shark Power

Sharks sport two kinds of muscle (shown here): red muscle for endured activity and white muscle for short bursts of energy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ostrich Shape

Despite being a bird, an ostrich’s body shape reflects its ability to run as fast as 31 miles (50 kilometers) an hour, instead of its ability (or lack of ability) to fly.

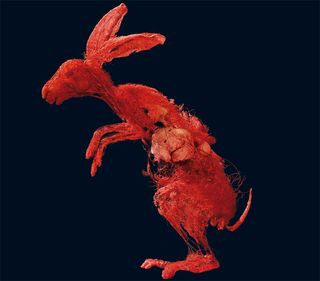

Bunny Bounds

A rabbit's skeleton is adapted to jumping. The bones are fine and the spine flexible, enabling rabbits to make powerful leaps.

Turning a Rabbit Red

A colossal network of blood vessels exists inside animal bodies. The arteries in this rabbit help deliver blood from the heart, repeatedly branching into smaller and smaller vessels to reach every extremity until they become hairlike capillaries.

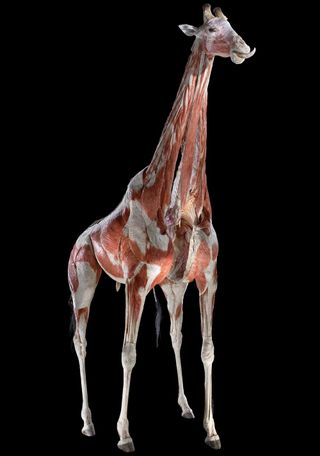

Towering Titan

The towering giraffe has an exceptionally long neck, but the same number of cervical vertebrae as a human: seven. Each is just much longer, helping to make the giraffe the tallest living land mammal.