Birdlike Dinosaur About to Lay Eggs When Death Struck

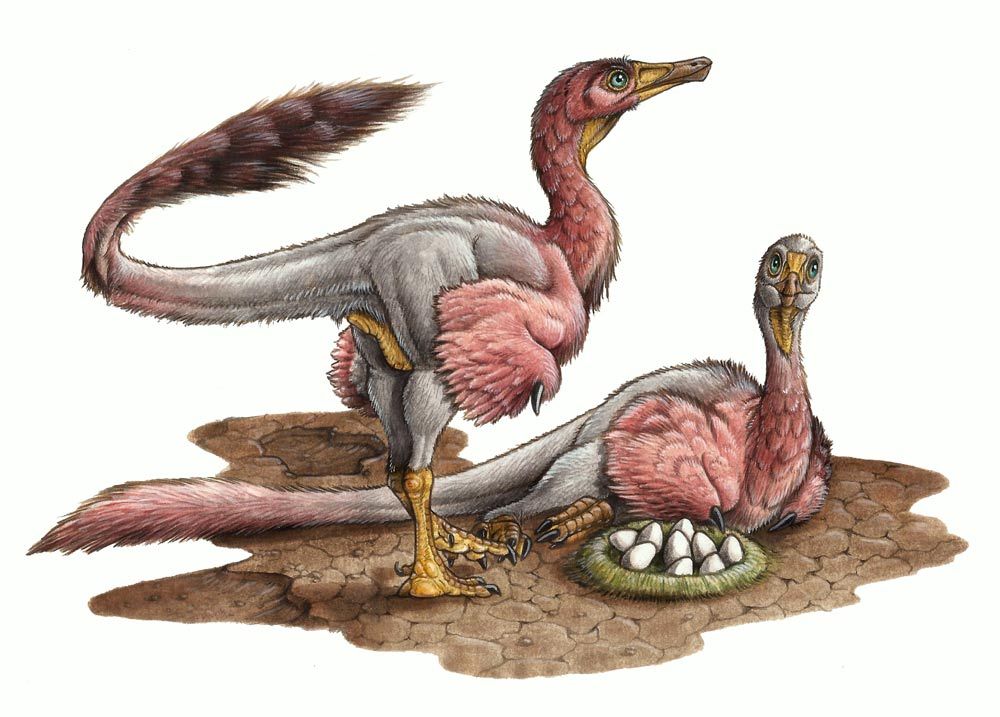

A mysterious birdlike dinosaur was about to lay her eggs when she perished some 70 million years ago in what is now Patagonia, researchers have found.

The scenario is based on the discovery of two dinosaur eggs lying near the partial skeletal remains of an alvarezsaurid dinosaur, which was a type of small maniraptoran, a group of theropod dinosaurs believed to be the line that eventually led to modern-day birds. Alvarezsaurids are bizarre among dinosaurs, scientists have said, due to their short, massive forelimbs tipped with a single digit sporting a gigantic claw. The dinosaurs also show highly birdlike skeletons, even though they were flightless.

The team named the dinosaur Bonapartenykus ultimus in honor of José Bonaparte, who in 1991 discovered the first alvarezsaurid in Patagonia.

The dinosaur eggs were found less than 7.9 inches (20 centimeters) from the partial skeleton and seemed to belong to that individual dinosaur. The researchers ruled out a postmortem mixing that brought the two together. The partial skeleton was also articulated, which would likely not be the case if they had been transferred there after death.

In addition, the researchers didn't find evidence of calcium resorption, which happens in the later stages of embryonic development when embryos suck up calcium for bone growth from the inner lining of the egg, according to study researcher Martin Kundrát of Uppsala University in Sweden.

After various microscopic analyses of the bones and eggs, along with eggshells found in the area, the researchers speculate the two eggs, each about 2.8 inches (7 cm) in diameter, may have been inside the oviducts of the female Bonapartenykus when she died.

"So it looks like we have indirect evidence for keeping two eggs in two oviducts," Kundrát told LiveScience. "They were close to being laid, but the female didn't make it."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When analyzing eggshell fragments, found to belong to B. ultimus, the researchers discovered fossilized fungi; such contamination affects bird eggs today, Kundrát said. "It looks like at the very late stage the eggs could suffer from the same contamination as in common birds," he said during a telephone interview. "It doesn't mean it must kill the embryo, because usually in the embryonic space or inner space it's still protected by a very dense network of organic fibers called the shell membrane."

This mama dinosaur would have lived on Gondwana, the southern landmass in the Mesozoic Era, which lasted from about 251 million to 65 million years ago. (The era is split up into the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.)

The finding, which will be detailed in the June 2012 issue of the journal Cretaceous Research, shows that early alvarezsaurids persisted in what is now South America until latest Cretaceous times, Kundrát said. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.